1. I. INTRODUCTION

he information age caused important restructuring processes in the workplace and in occupational structures, which changed organizational behaviours. Knowledge management was recognized as an important strategic element of human resource development (HRD) strategy to provide functional organizational behavior and performance (Gibbons et al. 1994). In this respect, current debates in knowledge management literature could be placed into a wider context of the management of knowledge workers in knowledge -intensive firms (Bell 1973), institutional innovation (Castells 1996), knowledge creation (Drucker 1988), increasing flexibility of work conditions and autonomy and responsibility of the employees. The high growth rate of knowledge requires organizations to develop flexible organizational potential to match changing environments and keep up organizational competence (Laursen 2006). Increasing flexibility in the labour market and within organizations creates opportunities for employee mobility, which challenges organizations as they lose their best talents. It is a paradox that the willingness of knowledge workers to work hard and is because of shifts in traditional upward Author ? : Assistant Professor (SG), E-mail : [email protected]. Author ? : P.GStudent, E-mail:[email protected].

?? VIT Business School, VIT University, Vellore-632014, Tamil Nadu, India .

career development pathways (Carlsen, Klev, and Krogh 2004).

In increasingly flexible conditions, HRD managers try to retain workers by developing strategies that empower individual employees. The HRD department as a key strategic unit within an organization is responsible for creating favourable conditions for career development. This paper will analyse how developments in HRD empowerment practices for retaining knowledge workers paradoxically contribute to greater autonomy and independence. These practices have further implications for employee individualization and alienation from the workplace, resulting in greater mobility.

Furthermore, increasing employee individualization contributes to outsourcing responsibilities and duties, which increase stress, doubt, uncertainty and ambiguity among the employees. The current paper will develop and present an analytical perspective from which to study empirical research based on secondary data from a HRD department in the Danish high-tech company Bang & Olufsen (B&O). Empirical material will be analysed and discussed to understand the need for change in current HRD practice in order to meet and accommodate the changing nature of flexible career development patterns.

2. II.

3. ORGANIZATIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWLEDGE WORKERS

Addressing these research questions requires elaboration on the concept of knowledge necessary to view organization, organizational behavior and organizational learning as a certain analytical tool. According to Davenport (2005), organizational structures at the workplace become increasingly knowledge-intensive and involve people, processes and technologies, thus increasing the role of the knowledge workers. Furthermore, organizations become heavily dependent on this type of workers as long as most organizational work is dematerialized (Luker and Lyons 1997). However, concepts of knowledge work, knowledge worker and knowledge-intensive organization introduced by Drucker are quite ambiguous (Newell et al. 2002).

Knowledge-intensive firms are organizations where most of the work is of an intellectual nature (Alvesson 2001). Knowledge workers are defined as hard-working and committed employees with a high T degree of expertise, education and experience. They add the most economic value to organizations, and determine growth and profitability. Knowledge work as 'thinking for living' is related to problem solving, decision making, collaboration and extensive communication. For knowledge workers, knowledge is simultaneously an input, medium and output of their work (Frenkel et al. 1995). Due to nature of their work, knowledge workers require high levels of autonomy, as they decide how to initiate, plan, organize and coordinate their own tasks (Gherardi 2006).

The discourse on knowledge management in organization studies appeared in the 1970s and embedded the concept of learning in organizational practice (Gherardi 2000).According to the early discourse, knowledge is stored in the heads of individuals; this is based on traditional cognitive theory. It rests upon high levels of individual autonomy, cognition and the banking concept of knowledge (Hooks 1994). The second discourse approaches knowledge through the knowledge management perspective as a productive strategic commodity in organizational management. There is no practical distinction between information and knowledge in this sense (Prahalad and Hammel 1990). Knowledge is embedded in organizational routines and the main objective is to provide knowledge transfer and not knowledge transformation. Arising from the first discourse is the problem of transferring individual knowledge and learning outcomes from knowledge workers to organizations (Elkjaer 2006). Hence, even a high level of individual competencies does not guarantee functionality of an organization.

In the second discourse, the limitation is that the focus is on a greater level of power of organizational management, thus ignoring the individual subjective knowledge processes. It focuses on the control of knowledge in the economic interests of organization. These individualized and static views on knowledge and knowledge work contrast with the perspective that strategically important knowledge of organization is produced in collective working practices, cooperation and day-to-day problem-solving. This paper focuses on the knowing process that is: knowledge embedded in practice (Cook and Brown1999). It will present knowledge as an active, highly situational and contextual concept where individuals give meanings to information and contribute to knowledge creation (Nonaka 1994).

The main assumption made in the paper is that knowledge in organization does not have any meaning on its own without enactment. In this respect, the organizational learning literature presents an active definition of knowledge where it represents not mere external representations but rather guides human activity (Argyris 1999; Argyris and Schon 1978; Ravn 2004). From a pragmatist's perspective, knowledge is understood not as static and abstract phenomenon but rather as an active process of knowing that is embedded in dynamic human actions. Knowledge is not an object shared materially (Dewey 1916) but socially constructed through cooperative efforts with common objectives. It is built in the artifacts, behavioral pattern sand actions, and calls for an' epistemology of practice'. Consequently, knowledge is kept neither in the head of individuals nor is it a commodity of organization and its management (Tsoukas and Vladimirou 2004). Organizational learning in this perspective is a process that occurs as a result of the actions of organization's members being simultaneously influenced by the collectively accepted knowledge. The paper will develop a theoretical framework to address relationships between the individual, organization, knowledge and action. The paper will analyse how knowledge is connected to action and discover the prerequisites for HRD practices in order to make effective interventions, direct individual actions and knowledge-use in organizations.

4. III.

5. ANALYTICAL FRAME AND CONCEPTS

The current paper will develop a theoretical framework that incorporates a theory of activity (Engestrom 1987) and a concept of learning progression (Laursen 2006). The paper will address a flexible organization structure and HRD practices with an active definition of knowledge. Namely, it will consider knowledge through 'know-how' rather than 'know-what' (Laursen 2006). The knowledge criteria are defined by knowing how they are primarily related to actions, intentions, relations and context (Polanyi 1966). Hence, this paper will be focused on knowing and how people 'do their knowing', and will present the organization as an infrastructure of knowing (Blackler, Crump, and McDonald 1999a).

The reason for choosing an active concept of knowledge is to analyse the process by which organizations create knowledge through individual actions based on autonomy, commitment and individual responsibility. Furthermore, it is necessary to consider the organizational context in which individuals undertake their actions. The concept of activity setting and theory of activity provides a significant departure point in current analysis of organizational context.

6. IV.

7. ACTIVITY THEORY

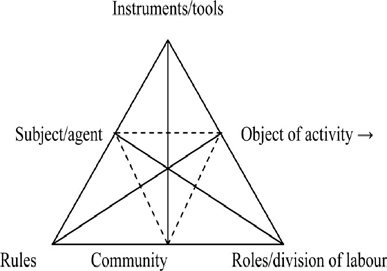

An activity theory is a useful analytical tool to analyse relationships between knowledge and action, individual thoughts and collective beliefs (Blackler 1993). It bridges the literature of organizational learning between psychological and social, thought and action, theory and practice. The main concept to describe activity is the activity system presenting the context for individual actions (Engestrom 1987). The activity actions in the activity setting through agents, their objectives, tools and language in use within the broader social and cultural setting of an activity system.

The goals and objectives of the given activity system are partly predefined for those involved through rules, culture and division of labour, and in part recreated and modi fied by individual actions. Tools and instruments mediate relationships between individuals and their contexts. Rules mediate relationships between individuals and community. The division of labour mediates relationships between actions and its members. The concept of mediation here refers to the fact that they transform the nature of contexts within which individuals act (Figure 1).

According to activity theory, knowledge is neither an individual nor an organizational commodity (Blackler, Crump, and McDonald 1999b). Knowing is active achievement and social construction through which individuals 'do their knowing'. Doing and knowing are achieved by culturally developed resourcescharacter of practices, tools and technologies. In an organizational context, these resources represent a knowing infrastructure. Thus, how an organization knows depends on interactions between individual cognitive processes, community members and shared knowledge infrastructure. Rather than studying knowledge owned by individuals or organizations, activity theory studies knowing as something that they do and analyses dynamics of systems through which knowing is accomplished (Blackler 1995). An activity system represents relationships between individual knowledge and knowledge infrastructure, individual action and broader patterns of activity. Thus, activity links events to the context within which they occur. Organizations provide a context for actions while individuals interpret and negotiate context. This includes complex organizational routines (repetitive patterns of behavior) and conditions. Together these factors create knowledge infrastructure through which knowing and doing is achieved in organizations. V.

8. PROGRESSION

The emphasis on knowledge in organizations raises fundamental questions of learning, namely how knowledge workers acquire relevant competencies and transform their actions (Elkjaer 1995). In this respect, progression is considered as development of learning infrastructures, which lead to the development of learning opportunities (Laursen 2005). In response to individual actions, a learning organization facilitates the learning of its members and continuously transforms itself (Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell 1991). A learning organization develops a wide range of structured social situations -learning opportunities -described as learning infrastructure. In this learning infrastructure, the focus is on collective agency where a group constitutes a collective learning system and depends on how its structures meet the conditions of learning, i.e. Create learning opportunities (Salomon and Perkins 1998).

The social situation of learning represents the organizational capability for learning. The progression within a learning organization follows the development of social structures inside an organization and involves employees in learning. Here the flexibility of organizations is defined as a constant transformation of organizational resources that provide continuous opportunities for individual members to learn and expand their knowledge (Senge 1990). In this sense, individual employees have to decide how the job is done and what quality job performance is. However, social structures in organizational relations create a general framework and social context for individual learning in organizations (Laursen 2005). Consequently, organizational learning is not based on a banking concept of individual knowledge and competence container.

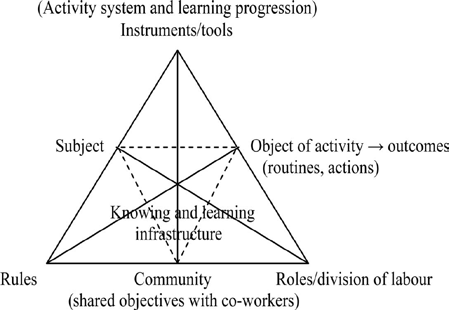

It is rather viewed as the development of social contexts and the existence of organizational infrastructure of learning and knowing through which knowledge is produced, acquired, evaluated and transformed. Integrating the analytical concepts of an activity system and learning progression makes it possible to develop a modified model of the knowing and learning in flexible organizations (Figure 2). In this model, learning and knowing are considered as situated activities -social interactions among social actors drawing on contextual resources that are knowledge and learning infrastructures (Layder 1997). The key elements linking processes of social interactions are tools, techniques, norms and social structures (Engestrom 1987). Social structures can function as constraining or facilitating elements for individual actions.

Consequently, learning opportunities (progression) are social processes of interaction structured by sets of contextual resources transforming the knowledge base and producing progressive changes in individual actions.

9. BANG AND OLUFSEN: BACKGROUND FOR HRD DEPARTMENT

The qualitative analysis is based upon secondary data from the Danish high-tech company Bang and Olufsen (Krause-Jensen 2002). Analysis involves the study of data derived from documents, field notes, transcripts of interviews and observational records. Bang & Olufsen (B&O) is a Danish high-tech company distinctive for its design. At the end of the 1990s, the company launched a project that defined and communicated company values, which lead to organizational mobilization and cohesion.

HRD became a strategic element in transforming B&O from a product-focused to valuedriven company. A human resources department was formed as the result of a fusion of two departments: an employee centre (medarbejdecenter) with fourteen employees and a smaller HRD unit with only four employees to overcome fragmentation and dispersal at the social level. The former employee centre was a personnel department that serviced mostly nonmanagerial employees. The latter HRD unit was a small group that worked with senior management on strategic issues of organizational development. The integration of the two departments and the appointment of a new head of HRD emphasized that personnel issues were given strategic importance in developing comprehensive personnel policy.

With the fusion of the two departments, the company decided to mobilize and empower employees through a value-based rhetorical strategy for creating organizational flexibility and autonomous self-managing employees (selvkorende medarbejder). The point of integrating 'medarbajdcenter' and HRD was to upgrade the entire personnel area and increase a sense of belonging to the company: 'all employees should feel that they contribute to strategic development of the company' (HRD top management).

The new HRD department tried to establish a clear departmental profile and have its contribution recognized by the rest of organization through legitimization of renewed HRD activities. At the first stage, HRD was struggling to get rid of its 'welfare image' associated with previous personnel policies. The change in policy involved giving HRD a new strategic vision. It implied a shift towards soft forms of control associated with value based management and facilitated autonomous self-managing employees. At the same time, the fact that HRD was considered strategically relevant and given unprecedented visibility within organization meant that it had to legitimize its activities in new ways, vis-à-vis hard business realities (competition, product development, etc.).

10. VII. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

The idea behind the fusion of the HRD department with the personnel department at B&O was to create structure with coherent, comprehensive employee policies to fit in with new values of the company. One of the most important tasks was to ease communication, help the vision of the HRD manager is based primarily on reciprocity between organizations and single individuals, and is based on contractual and exchange relationships. The reformed HRD strategy shows that employees are looked upon as a source of competitive advantage through their commitment, adaptability and high quality (Guest and Terence 1983).

In new vision, employees should be proactive rather than passive inputs into the productive processes and capable of development in exchange for increased personal autonomy and self-management. This clearly demonstrates a highly individualistic approach to empowerment and the motivation for development of employees. The centrality of the individual and the ways in which the individual is conceptualized are unchallenged: 'If I look at people's motivation for working, it is all about individuals' working to make a difference.

It is important to know where employees fit into things, and it is vital that progress is noted and development monitored, so that people can see that their work is successful. Anything else would not be reasonable from both commercial points of view and individuals 'self-esteem' (HRD assistant).

Hence, HRD remains a management rather than a development function By doing so, HRD acts as a political tool of regulation constituting individualized HRD practices. The vision of a 'new HRD' jeopardized the success of the HRD strategy from the very beginning by creating a gap between organization and individual, constituting the self-managing employee and contributing to the visions of a fragmented society in a position where managers needed to accommodate individual aspirations and interests within the strategic interests of the organization. It had to negotiate relationships between individuals and organizations in a particular way, so that HRD employees simultaneously represented producers, gatekeepers, communicators and consumers of the corporate messages bringing individual and organizational growth into alignment (Krause-Jensen 2002). SELF-MANAGING EMPLOYEE (SEVKORENDE MEDARBEJDER) VIII.

11. SELF-MANAGING EMPLOYEE (SEVKORENDE MEDARBEJDER)

Aspiration depends on the negotiation process based on tact and diplomacy: 'People's attitudes towards me can be described in two ways: 1. I am the tool of the management to manipulate the staff, and 2. I am here to protect the staff from duality. Namely, HRD ended up According to the HRD manager of new integrated department, coherence between organizational and individual the company. They are both wrong. I am on the side of the work. Both the staff and the company share the interest in ensuring that the staff gets most out of their work and the company gets most out of their staff' (HRD manager).

However, the transformed HRD department faced the dilemma of individual aspiration vis-à-vis the organization's vision. The major challenge for the HRD department was to overcome individual organization However, it is questionable whether the mediatory role of HRD in B&O is able to bring the rhetoric of change and challenge has become prevalent in corporate discourse, and management stresses the ideal of developing a proactive, self-managing and 'selfstarting' change agent: 'Only an HRD department with a clear and common understanding of its own ambitions vis-à-vis the business plan can accomplish its tasks. Growth is conceptualized as moving from a state of dependency and embeddedness with others to a relative state of independence and autonomy where individuals acquire tools 'to develop and find themselves'. B&O management stresses the importance of the ideal member of organization -the self-managing employee (sevkorende medarbejder), a presupposing motivated and entrepreneurial worker offering workplace knowledge and experience. In this sense, employees have to be directed through the inculcation of certain attitudes, behaviours and views of themselves vis-à-vis the organization.

The strategy of the company is to create a situation where employees manage themselves and are guided by implicit motivations. According to Keat (1991), the ideal self-managing enterprising individual is one that is keen on responsibility; goal-oriented; concerned to monitor their own progress towards goal achievement; motivated to acquire skills and competencies; and has the resources necessary to pursue these goals effectively.

The meaning of subjective involvement of liberated individuals exhibiting autonomy and responsibility is implicit in the new social contract, best characterized by the notion of 'individual responsibility' (Schots and Taskin 2005). Namely, employees are given new responsibilities; they become proactive, show initiative and commitment, and take risks. HRD practice intends to increase the self-management of workers but in response encounters a trade-off in the face of increased individualization. According to an employee from the B&O Man/Machine Interface technology and multimedia department, 'If you want to move forward in a company like B&O, you have to fight for it. You have to draw attention to yourself. If you are not in demand and you can't deliver your goods, then you are out! If they cancel their appointments and your calendar gets empty, then you are in trouble. I have always been supposed to find my own assignments.' Therefore, HRD development is leading to increasing individualization through greater in-group competition, mobility and flexibility related to the career progression of the workers as well as the transfer of risk to individual employees. Individual autonomy appears to be an ambivalent concept, as individualization of objectives and performances reinforces mental burden. The ambivalence is because the increase in autonomy and responsibilities transfers certain risks to employees: they become responsible for their own professional development and management in order to become visible in organizations: 'It is also true that when I put so many hours, they notice me, and creating a constant need to meet organizational requirements. While the HRD practice intended to constitute a social innovation -self-managing employee.

-it contributed to fragmentation of collectivity that exposed employees to high individual and social risks.

I get the benefits' (IdeaLand employee, R&D department). In reality, the risk transfer contributes to intensification of workload and may lead to increase in stress and alienation from the workplace (Taskin and Devos 2005). Consequently, while HRD practice makes people autonomous and self-managed, it constrains their actions Learning new skills and competencies. But these higher levels of participation are structured in less visible ways and employees become accountable for outcomes that were once the responsibility of supervisors and managers (Krause-Jensen 2002). Hence, the empowerment of the employees paradoxically constrains and constricts their actions.

12. IX.

13. PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT-FROM SELF-MANAGEMENT TOWARDS SELF-DEVELOPMENT

The new communication strategy of the HRD department resulted in flattening and removing traditional hierarchies: 'Years back you would feel the bad breath of your subordinate over your shoulder. Now I meet my supervisor once or twice a week, and I appreciate the trust that the company puts in you, the space you are given to plan your own day and to arrange your own job, we have a lot of possibilities to develop' (Product Development Department employee).

However, in reality employees face the disappearance of aspects related to the reward system, security and career development. When hierarchies are flattened or removed, and where vertical movements previously served as external guides for sequences of work experience, employees are now forced to rely on the internal self-generated guides devolving responsibility for growth, learning and development. The product development (PD) department came to be seen by many employees as the core of company. According to the HRD recruitment officer, there was a clear migration pattern towards the product development department. Once employees were in the PD, it was difficult to convince them to move to other parts of the company.

This assumed prestige was because work in the PD was close to the product and because employees were engaged in development as opposed to other operational departments (Krause-Jensen 2002). This preference for development was reflected in the internal mobility of employees. On the product side, there was a migration pattern from operations towards product development, and from central purchasing and sales towards marketing. These movements' reflected orientations from areas concerned with operations to strategic spots closer to tasks related to strategic development. A young sales manager in the customer centre expressed a general preference for PD: 'It is my dream job to work there (PD) where things are happening and what you do has impact. We are put into this world to be innovative, and that is the challenge, to take responsibility and break new ground all the time.' However, the employee mobility to PD implies that individual employees have a responsibility to develop their own competencies. The employee mobility trend shows employees need to ' fit in the organization', develop and offer the right competencies valued by the organization. Employees become self-managers of their competencies and of their career paths as well as their development opportunities. However, due to nature of the job, employees carry out dematerialized knowledge work, which is not seen physically as tasks. Consequently, employees do not perceive their work to add value to their reputation and in 'becoming visible'. In their opinion, 'much of the work does not appear to the rest of organization as a genuine specialist activity involving unique knowledge and skills'. Consequently, employees intensively express a high need to 'become visible' implying the need to reestablish interaction with the organization and overcome social fragmentation. The new HRD practice in B&O demonstrates that the HRD strategy for employee empowerment -to develop self-managed, autonomous, and responsible and flexible employees -contributes to increased employee competition; creates alienation from the workplace; and produces less predetermined career path and employee mobility towards different units.

Furthermore, it had implications for increased individualization through the search for learning opportunities for personal growth and the need to fit into an organizational context rather than develop organizational commitment. All this reflects the employee's need to become 'visible' in the organization, thus constraining individual opportunities for action and increasing stress and competition. HRD practice constitutes a lack of knowledge creation and sharing, thus contributing to knowledge fragmentation and having negative consequences for organizational learning. Furthermore, HRD practice, in this perspective, acts as a tool of exclusion. It excludes the benefits of the group and teamwork, social interactions and those employees who are unable to position themselves in a favourable way according to the new vision X.

14. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

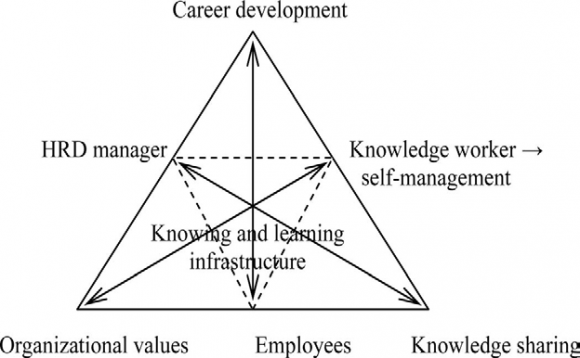

The current paper questioned HRD practice at the workplace: a HRD strategy based on individual empowerment directed towards developing autonomous employees. The research demonstrates that individual self-management creates a high risk for employee individualization, alienation from the workplace and a lack of knowledge sharing leading to ineffective organizational learning. This individualizing HRD practice contributes at the same time to fragmentation of organization, exposes individuals to social risks and creates exclusion among the collective. In contrast, the successful managerial discourse of the company would mediate organizational paradoxes, considering dualities such as flexibility and loyalty, individual alism and commitment, responsibility and alienation. Such HRD systems could contribute to the capacity of an organization to learn by facilitating the development of organization-specific competencies in complex social relationships based on the company's history and culture, and generate organizational knowledge. Hence, the current analytical perspective gives the opportunity to view HRD practice through 'activity' and 'progression' lenses. The object of the current activity system is the knowledge worker, who represents raw material or the problem space in which activity is directed and transformed through appropriate tools into the outcome of the self-managed employee. Organizational values are the social rules presenting implicit and explicit regulations, conventions and norms constraining or facilitating the interactions with the activity system as well as the relationships between subjects and other employees (Boer, Baalen, and Kumar 2002).

The employees represent a community or group of actors sharing the same object of activity that is distinct from other groups. Finally, knowledge sharing is a process of division of labour, which refers to both a horizontal division of tasks as well as a vertical division of power and status. Hence, the model presents a multivoiced HRD practice in a relationship between subject (HRD development) and object (knowledge worker) mediated and guided by a set of structural non-causal relationships.

The model proposes HRD practices as a system based on actions, tools, technologies, social structures, rules, and problems of particular organizational contextual conditions analytical framework is that it provides the possibility of analyzing organizational reality based on the conception of culture/competence. Furthermore, it points to the opportunities for development promised by engagement with knowledge and learning infrastructure where contexts are not seen as containers of behavior but as activity. The concepts and framework provide the possibility of overcoming dualistic thinking about the separation between individualistic and organizational thinking and knowledge. It presented a conceptually comprehensive and consistent structure in organizational learning and knowledge by presenting the organization in a wider social context.

The emphasis on individual development in the analysed case shows that HRD has an individualistic role rather than interactive and interpersonal influence for better knowledge sharing and organizational learning. The research implies that HRD should change its interventions in terms of how the individual is conceptualized to make knowledge become actionable in social contexts in order to create favorable conditions for knowledge sharing and organizational learning (Lopez2006).