1. Introduction to the Study

uxury is viewed as a level of prestige to an extreme level of conspicuous consumption activity of consumers backed by the motive to exhibit a social status (Vigneron & Johnson, 1999). As highlighted by Shuckla (2010) and Tynan et al., (2010) the emerging countries identified such as Brazil, Russia, China and India have shown a greater interest for luxury consumption. The consumers in these countries seem to be showing more symbolic ownership of the brands primarily influenced by both symbolic brand attributes and the non-utilitarian brand attributes. Further, the changes in the society need to be considered every time Jelinek (2018). The behavioural patterns in the society showcase the social distinctions among the consumers and symbolic ownership of brands (Batra et al., 2000;Akram et al., 2011). According to Sukla and Purani (2012) the recent economic development in the emerging markets fuels the growth of luxury brand patronage that will lead the industry creating more opportunities for brands. Sri Lanka is such a country where the global luxury cars get a significant demand backed by the increasing purchasing power of growing high net worth individuals.

Jain, Roy and Ranchhod (2015) suggested that the changing profiles of the Asian consumer have significantly affected the inflow of luxury brands to the South Asian countries such as India. Therefore, there is a significant urgency for the luxury brand marketers to study the consumer attitude and perception in these parts of the world where different values, beliefs and attitudes prevail towards global luxury car brands. The global luxury spending has jumped up significantly and it is expected to reach USD 40 Trillion by the year 2020 (Assochamorg, 2013).

Previous research studies conducted have attempted to emphasize the role of a country's culture and its influence of demographical factors on luxury brand consumption (Hung et al., 2011;Godey et al., 2013). However, as Miller and Mills (2012) suggested the meaning of luxury could vary from country to country with its cultural uniqueness. Further, the consumer motivations and their objectives which are behind the purchase could be similar (Hennings et al., 2012). Researchers have shown their interest conducting research with the investigation perspective into the luxury branding from the view of the practitioner's perceptive (Fiondaan Moore, 2009) and from the conceptual point of view (Miller & Mills, 2012;Ghosh & Varshney, 2013).

Luxury has been discussed by many researchers with respect to the luxury automobile market. As the global millionaires grow and along with the growth of discretionary income of mass consumers who are identified as democrats, the luxury car market has shown considerable growth (Barnier & Rodina, 2006;Wiedmann, Hennigs & Siebels, 2007;Husic & Cicic, 2009). In addition to that, according to Lipovetsky and Roux (2015) the democratization has fueled the demand for prestige car brands and drawn the attention of marketing practitioners as well as academic researchers (Dubois, Czellar & Laurent, 2005;Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). The literature shows that the term luxury has been viewed differently by scholars. Therefore, the literature presents an exploration on an intellectual journey into the historical evolution of marketing research in global luxury branding. This paper attempts to explore the historical and theoretical evolution of luxury consumption and develop a conceptual model for luxury car brand purchasing attitude.

2. II.

3. Historical Evolution of the

Consumption of Luxury Hume (1752Hume ( , 1965) ) explained that luxury could be identified as a word of uncertain meaning and be considered both good and bad. Smith (1776) proposed that to a certain degree, consumption has a relationship towards the improvement of social standing or maintenance. The history of research into the subject of luxury goes to the 19 th Century (John Rae, 1834; Thorstein Veblen, 1899; & Keasbey, 1903). It was Veblen (1899) who discussed luxury consumption as a status symbol with social comparison. Veblen (1899) published 'Theory of the leisure class' and it was he who pioneered research on luxury consumption. Veblen (1899) suggested that lavishness in consuming products exhibits distinction and status to others. This concept was developed based on the premise that consumers have a desire to exhibit higher social class and represent particular economic groups. This was named as conspicuous consumption. Weber (1930) proposed that savings and investment are identified as economic activities of an individual. The Veblen effect was further reviewed from the work of Bourne (1957). Leibenstein (1950) based on the Veblen's theory, further argued that interpersonal values such as snob effect and the effect of band wagon are two variables to the Veblen effect. Both Veblen (1899) and Leibenstein (1950) argued on the value of status in luxury consumption. Scholars furthermore found uniqueness as the center of motivation for brands rousing their use (Leibenstein, 1950).

Luxury has been viewed as the things that people use to portray their personality to others through the common ramifications that the things contain (Levy, 1959). According to Yamey (1964), an anthropological study conducted on saving, capital, and conspicuous consumption, in several primitive societies they found this process as a display of wealth which was considered to be a wasteful activity. The luxury definitions have been numerous (Davidson, 1898). Therefore, the perplexity of the people is in many occasions is excusable. Grossman and Shapiro (1988) identified the luxury goods as the ones which are used merely or displayed on a particular brand that confers the value of prestige on theirs other than the utility derived from the function. Luxury is an extravagant living, over indulgence, luxuriousness, sumptuousness and opulence Oxford Latin Dictionary (1992). Dubois and Duquesne (1993) explain that motivation of the consumer is to inspire the others. It is their ability to pay high prices and this type of consumption is particularly characterized by flamboyant exhibition of wealth. Dubois and Paternault (1995) rather than the other products, luxury goods are purchased for the meaning beyond what these goods are. Kapferer (1997) defines luxury as beauty and it is the art which is applied to the product function. These products provide additional pleasure to all the senses at one time. It is the attachment of the classes of the society. There are other values such as quality, creativity and craftsmanship etc. (Kapferer, 1998). Further, this luxury consumption has been reviewed as a consumption activity for the glory of brands as explained by Mason (1981Mason ( & 1992)); Bearden & Etzel 1982). Kemp (1998) explains that luxuriousness of a particular good is determined by the product's natural desirability. It is not simply determined simply as an object for conspicuous consumption. Luxury products are identified as the brands which have a low ratio with its functionality to price, but the ratio of intangibility to the situational utility compared with price is high (Nueno and Quelch, 1998). An individual's functionality could be an another person's luxury (Bernstein, 1999). Exclusivity is evoked by the luxury brands. They have well-reputed brand identity and have high brand awareness as well as high perceived quality. These brands retain their sales and keep customer loyalty The important components of luxury products are brand identity, perceived quality, awareness and customer loyalty (Phau and Prendergast, 2000).

Luxury is defined as symbols of personal as well as social identity (Vickers and Renand, 2003). Luxury goods are the goods which enable the simple use or a product that displays a branded product offer esteem of the owner other than functional utility (Vigneron and Johnson, 2004).

Atwal and Williams (2009) define luxury as a concept traditionally associated with the terms exclusivity, status and quality. Luxury has an individual component too. What could be luxury to one person may not be luxury to another. It could be irrelevant and valueless to some other (Berthon et al., 2009). In luxury consumption, one communicates to create a dream and to recharge the product's brand value. It is not to sell (Kapferer and Bastien, 2009). Wiedman et al., (2009) define luxury concept as a subjective and multidimensional construct. It is a concept by definition that should follow an integrative understanding. Luxury goods are conducive towards pleasure and they give comfort. They are difficult to obtain and bring the esteem of the owner rather than its functional utility (Shukla, 2011). Luxury is described as old luxury together with consumer's self-indulgent and motivators of hedonism (Kapferer and Bastien, 2009; Shukla and Purani, 2012).

4. III. The New Era of uxury onsumption

Luxury is a concept that is very difficult to be defined and it is based on subjective judgements that could lead to different definitions (Vigneron and Johnson 1999;Yeoman, 2011). Luxury is an ambiguous concept (Dubois, Laurent & Czellar 2001). This ambiguity is related to the abstract and symbolic nature of luxury (Roux & Boush 1996). Therefore, to understand luxury, it is important to understand the dimensions of luxury and the attitudes towards luxury. The BLI scale developed by previous researchers: Vigneron Keller (1993) highlighted studying the consumer's behavior as a critical issue in order to make some strategic decision. Dubois et al. (2005) developed a concept with the traditional luxury view which states the luxury should be only available for the elite (labeled elitist) and modern luxury visionaries believe that everyone needs to have accessibility to luxury. Further, according to Dubois et al., (2005), the elitists indicated it was inevitable that luxury products be priced very highly. As noted, if luxuriousness diminishes, so does brand equity. To prevent this decay in equity, prestige businesses face a dilemma as they need to control brand diffusion to enhance exclusivity while at the same time maintain a high level of awareness (Phau & Prendergast, 2000). Rarity is also an important concept related to the equity of prestige brands (Dubois & Paternault, 1995;Kapferer, 1998). Yet it also causes a paradox (Roux & Floch, 1996). This contradiction results because it is natural for prestige brand managers to seek maximization of profits by selling as many products as possible; however, following a rarity principle suggests that to build equity, a prestige brand needs to avoid the risk of commoditization (Kapferer, 1998). Thus, rarity suggests that sales must be limited since too much distribution erodes being scarce, dilutes desirability and exclusivity, and consequently erodes brand equity. Dubois and Czellar (2002) added selfindulgence as a new luxury dimension. Further, it was discussed on the importance of hedonism of luxury brand consumption. Johnson (1999, 2004) proposed a theoretical framework for luxury brand consumption value which included personal and nonpersonal perceptions of value. Hedonism and quality were identified as personal dimensions while conspicuousness, social value and uniqueness were identified as non-personal consumption. As suggested by Camilo Koch and Davit Mkhitaryan (2015) in a research study carried out in China on consumers' choice in luxury car brand selection, consumers tend to expect benefits directly derived from the attributes. Consumers can be identified with respect to the products they buy and when the income level goes up of these consumers they tend to purchase more luxurious goods (Songer, 2014). According to Vigneron and Johnson (1999); Engand Bogaert (2010) and Ghanei (2013) the factors that could perceived quality, perceived hedonism and perceived social value. Further, Vigneron and Johnson (2004) suggested that if the amount of perceived luxuriousness can be managed, it could be measured as well. Brand Luxury Index (BLI) was developed in order to provide a tool to estimate the amount of perceived luxuriousness of a prestige brand based on the five components: conspicuousness, uniqueness, quality, extended self, and hedonism (Vigneron & Johnson, 2004).

5. IV. Dimensions of Luxuriousness and Terms

Keller (1993) identifies luxury dimensions as functional, experiential and symbolic expressions. Vigneron and Johnson (1999)

6. V. Modification of Perceived Luxury Value Dimensions

The concept of consumer-based brand equity (Keller, 1993) provides the rationale to investigate the question of modifying perceived luxury value since the concept emphasizes individual customers' reactions to the marketing mix elements. Kim and Johnson (2012) found in their research that price, distribution intensity, store image, brand personality and innovativeness had a significant impact on all components of perceived luxuriousness: quality, dominance, exclusiveness, and tradition. However, advertising expenditure did not influence perceived luxuriousness. Also price promotions negatively influenced participant's perceptions of three of the four dimensions of luxuriousness.

The modification for the Brand Luxury Index (BLI) was carried out by Kim and Johnson (2012) based on the BLI scale developed by Vigneron & Johnson (2004). The four variables identified in the modified BLI scale were quality, dominance, exclusiveness, and tradition. This is in comparison to the previous model of five dimensions; conspicuousness, uniqueness, quality, hedonism, and extended-self. When compared with the original BLI scale, in the revised scale the exclusiveness dimension was included instead of the conspicuousness and uniqueness dimensions. Hedonism was also eliminated in the revised model. However, the items included under the hedonism, have been included under the other luxury dimensions of the revised BLI scale. Further, tradition was added as a new dimension to measure the perceived luxuriousness (Kim & Johnson, 2015).

7. VI. Luxury Perception and Consumer Brand Attitude

Consumers as individuals identify the term luxury with expressions such as upscale, good in taste, quality, and class, etc. It is evident that people fulfil their functional requirements through luxury but also the psychological requirements (Dubois, Laurent & Czellar, 2001). Widemann, Hennigs and Siebels (2007) describe that the luxury value has three fundamental dimensions: functional value, social value, and individual value. Luxury perception. According to Vigneron and Johnson (1999), Eng and Bogaert (2010) and Ghanei (2013) the luxury perception is linked with five values and that could make a differentiation on luxury and the non-luxury brands through perceived conspicuousness, perceived uniqueness, perceived hedonism, perceived quality and perceived social value.

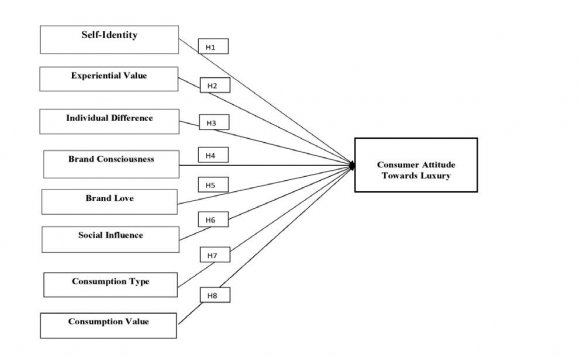

Perception is described as the way we see the world around us and the identification and interpretation are highly dependent upon the needs, values, and expectations of an individual and it is individualized (Schmitt, 1999). Attitude Towards Luxury a) Hypotheses Vigneron and Johnson (2004) concluded in the brand luxury index that self-identity plays a significant role towards the consumer attitude towards luxury. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed as; H1: There is a relationship between Self Identity and the Attitude Towards Luxury.

Consumers are driven by the consumer's experiential value gained (Brakus et al., 2014;Schmit et al., 2015). Yeoman (2011) states that there is a positive relationship between the consumer experiences and the perceived value of luxury. Thus the below hypothesis is developed as; H2: There is a positive relationship between Experiential Value and Attitude Towards Luxury.

According to Miller and Mills (2012) the differences in culture impact the individuals to define luxury. Further, Godey, et al. (2013) too confirmed the relationship between differences in culture and luxury consumption. Thus, the below hypothesis is developed as;

H3: There is a relationship between Individual Differences and Attitude Towards Luxury. Sproles and Sproles (1986), state that brand consciousness act as one of the key decision making styles. Brand love is the positive attitude a brand (Batra, et al., 2012). Brand love has an impact on the consumer's attitude towards luxury. Luxury brands are normally purchased by considering that they are not necessities. A consumer with brand-conscious behavior tend to perceive brands as symbols of status and prestige (Liao and Wang, 2009;Giovannini et al., 2015). Therefore, the following hypotheses are suggested as; H4: There is a positive relationship between Brand Consciousness and Attitude Towards Luxury.

H5: There is a positive relationship between Brand Love and Attitude Towards Luxury Cars.

The motivation of consumer's social consumption states that consumers purchase brands not only to acquire brand, but also for social status aspect of consumption and meaning (Fitzmaurice and Comegys, 2006;Gil et al., 2012). Social influence has also been researched in the luxury brand consumption behavior (Weidman, et al., 2009). Therefore, along with these empirical findings, the following hypotheses are developed as; H6: There is a positive relationship between Social Influence and Attitude Towards Luxury.

The desire for conspicuous consumption or for gaining social status should directly affect the attitude toward luxury brands (Dittmar, 1994;Weidman et al., 2009). Bearden and Etzel (1982) explained that the luxury brands consumed in public tend to be more conspicuous than luxury brands consumed in private. Therefore: H7: There is a positive relationship between Consumption Type and Attitude Towards Luxury.

Combining the works of Vicker & Renard (2003) and Vigneron & Johnson (1999), which looked at the role of symbolic, hedonistic, materialistic and utilitarian values on attitudes towards luxury brands, as well as impacting feelings toward a particular brand, the following two hypotheses were developed: H8: There is a positive relationship between Consumption Values and the Attitude Towards Luxury.

8. b) Proposed Conceptual Model for Factors Associated with Consumer Attitude Towards Luxury Brands

The proposed conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1.1. Self-Identity, Experiential value, Individual Differences, Brand Consciousness, Brand Love, Social influence and Consumption type are identified as independent variables. Consumer Attitude uxury is taken as the dependent variable. towards L VIII.

9. Conclusion and Managerial Implications

Global luxury spending has jumped up significantly and it is expected to reach USD 40 trillion by the year 2020. Previous research studies have attempted to emphasize the role of a country's culture and demographics with luxury brand consumption (Hung et al., 2011;Godey et al., 2013). However, as Miller and Mills (2012) suggested, the meaning of luxury could vary from country to country with its cultural uniqueness.

Further, consumer motivations and objectives which are behind the purchase could be similar (Hennings et al., 2012). Many luxury branding studies have been conducted from the perceptive of the practitioner (Fiondaan & Moore, 2009) and from the conceptual point of view (Miller & Mills, 2012;Ghosh & Varshney, 2013).

Consumer attitude has been a widely discussed topic in research and it is important to study consumer attitude in order to identify the consumer decision making process. L uxury brand attitude towards a product depends on the consumer's perception of the brand. The dimensions of luxury have been evolving over in the past from among the researchers such as Managing luxury dimensions successfully will enable marketing managers to manage their brands effectively by managing the consumer attitudes. It facilitates the effective decision making of business organizations and will benefit consumers as well. Luxury could vary from country to country and culture to culture. Marketing communication strategies could be effectively managed with the careful identification of the target audiences. Specially in designing the culturally sensitive advertisements. Further research could be carried out to study the effect of consumer attitude towards the luxury car brand purchasing behavior.

| dimensions into conspicuousness, uniqueness, quality, | |||

| hedonism and extended-self. Vickers and Renand | |||

| (2003) | suggest | functionalism, | experientialism, |

| symbolism, and interactionism as luxury dimensions. | |||

| Berthon et al., (2009) defined luxury dimensions as | |||

| functional, experiential and symbolic expressions. | |||

| Further, Brakus et al., (2009) suggest behavioral, | |||

| feelings and cognition dimensions as luxury dimension. | |||

| developed the | |||

| Year 2020 |

| Volume XX Issue I Version I |

| ( ) E |

| Global Journal of Management and Business Research |