1. Introduction

he knowledge identification is the beginning of the knowledge management process. However, insufficient existing empirical evidences are unable to sufficiently endorse the linkage between knowledge identification and knowledge management. Further, researchers are not adequately evaluating the extent of which the knowledge identification brings an impact on knowledge management in today's knowledge intensive economy, where the new knowledge can be used to achieve the sustainable competitiveness (Tow & Kim, 2017). Ortiz, Donate & Guadamillas (2017) argued that knowledge identification capabilities available in a firm enable to accelerate the amount of knowledge required by the firm. Once the right knowledge has been identified, it should be captured and use as an ongoing activity for the benefit of the organization and need to be successfully distributed across the organization as well. Otherwise, the new knowledge will be deteriorated or perish quickly; wasting time and investment made in the process of identifying the critical knowledge asset. argued that effective knowledge use is one of the knowledge management processes and both knowledge acquisition and effective knowledge use maximize organizational returns (Smith & Lyles, 2011; Hislop, 2013). pointed out that knowledge identification has a positive and significant effect on the innovation capacity of Small and Mediumscaled Enterprises (SMEs). Moeuf, Lamouri et al. (2019) argued SMEs identify new knowledge internally or through many other external sources or in both ways, anyway, right knowledge identification effects on the success of SMEs. Doran et al. (2019) argue the SMEs generate knowledge internally. Jeong, Chung & Roh (2019) argued that both internal and external knowledge flows bring an impact on improving products, process as well as innovation of SMEs. Those empirical arguments highlighted that SMEs are managing knowledge requirements either internally or externally.

Tan, Brewer & Liesch (2018) identify the exporting as the unique way of entering into international markets. From this perspective, SMEs to become success globally, identification of external knowledge is essential (Ferreras -Méndez, Fernández-Mesa & Alegre, 2019). However, identification of the right knowledge itself is not sufficient if the new knowledge has not been properly used in achieving performance. Therefore, owners, managers, and employees of those SMEs are required to play a proactive role, together, to capture and learn how to use that identified knowledge regularly for the betterment of SMEs, thereby achieve the higher performance (Hu, Williams, Mason & Found, 2019).

Many researchers argued that knowledge management is a strategic approach that enhances the performance of SMEs (Hassan & Raziq, 2019). The knowledge management practices and processes have an influence on the performance of SMEs (Iuliia, 2018). However, SMEs are practicing knowledge management incidentally or informally (Andronikou, 2018). Becker, Jørgensen & Bish (2015) argued that SMEs often identified critical knowledge more in an informal way. Nevertheless, identified new knowledge and its application help SMEs in many ways in improving performance .

These empirical findings highlighted that new knowledge has to be identified and the new knowledge to be used to enhance organizational performance, thereby to compete in today's competitive business environment. However, the SMEs are poorly understood the value of both knowledge identification and knowledge utilization . The SMEs more often use and adopt traditional knowledge management tools instead of newly updated, user friendly, cost-effective methods and intensively use knowledge management practices already they know and do not extensively focus on effective knowledge management process although SMEs could overcome its usual drawbacks such as financials and human resources with proper knowledge management practices despite the both knowledge management tools and knowledge management practices reinforces to other and vice versa (Cerchione & Esposito, 2017).

2. a) Research Objectives

3. Literature Review

a) The Knowledge-Economy Taylor's principles of scientific management (1911) argues the workers in the industrial economy were there to perform manual job tasks, and managers were there to get the work done. pointed out that knowledge decentralization was an effective in solving the economic problem rather than integration because knowledge decentralization enables proper use of knowledge when it has been found at a particular time and place. However, scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge. Arrow (1972) argued that knowledge is resource-driven and its profitability in welfare economies. Wernerfelt (1984) argument was that resources and products simultaneously reflect in two sides of the same coin. Barney (1991) and Miller (2019) pointed out those resources have been heterogeneously spread across the organization. Grant (1991) argued resource-based view of the firm believes profit maximization through economic resources. However, the transformation of industrial economies to the knowledge economy in which knowledge drives performance of the organization and the specialized knowledge categories available among individual employees are integrated and used towards production; accordingly, the value of knowledge application has been considered as vital than knowledge creation in knowledge-based view of the firm (Grant, 1996).

Accordingly, knowledge has been considered as the principal source of economic rent under the light of information age where the knowledge and its management are reflecting on knowledge work (Spender & Grant, 1996). Accordingly, to be in success in business, organizations are required to acquire specific knowledge and skills that would enhance business performances (Drucker, 1993), and organizations need to allocate such knowledge into productive use in organizational activities to gain competitive advantage and thereby to achieve best business performance to survive in the competition.

The production equipment had been the most valuable asset of organizations in the 20th century that mainly focused on manual worker productivity in manufacturing industries, however, with the dawn of 21st century, knowledge work and their productivity have been considered as the most valuable asset in the both business oriented or non-business-oriented organizations and the knowledge worker who processes those attributes is considered as the most valuable asset in organizations than a cost (Drucker, 1999). Garcia & Coltre (2017) further discussed the knowledge worker productivity recognizing the knowledge worker as a person who possesses a combination of both soft skills and hard skills. Hence, the role of the 'knowledgeworker' in emerging knowledge economies is still in existence.

4. b) Knowledge Categories

Polanyi (1962) argued knowledge consists of many domains; in some instances, kinds of knowing cannot be distinct from each other and mutually exclusive. The individual's knowledge that comes through actions, commitments, and experience, rooted through a specific context, is referred to as tacit. Accordioning, the tacit knowledge attributes an individual's quality, which cannot have been easily expressed. Polanyi (1966) described it as "There are things we know but cannot tell". On the other hand, Polanyi described the knowledge can be communicated through a formal or a systematic language, in the way of either words or numbers, and it is referred as explicit knowledge. Polanyi's two knowledge categories were discussed by (Nonaka, 1994) further elaborating on what Polanyi defined the tacit knowledge in a philosophical context. Nonaka argued the cognitive nature of tacit knowledge, which enables individuals to understand what is existing and also to visualize further directions of the firm. Accordingly, the tacit know-how is the image of the reality of an individual and vision for the future. The practical approach of tacit knowledge is further discussed considering its technical component from which an individual gains hard know-how, crafts, and skills in a specific context. Histop (2018, p. 18) argued those two knowledge typologies in the objectivist perspective, the explicit knowledge as objective and tacit knowledge as subjective. Durst & Leyer (2014) argued limited tacit knowledge, which has been centered among a smaller number of employees in the SMEs to be utilized and share within the firm as a remedy to losing such knowledge. Bojica, Estrada & Mar Fuentes-Fuentes (2018) pointed out that SMEs' ability to acquire different types of knowledge diminishes considerably. However, just being knowledgeable is not adequate for organizations to gain a competitive advantage in the knowledge economy, unless the new knowledge is created even at inter-organizational level or from outside sources, together, maybe in some, networking with all the stakeholders who are connecting with the business (Takeuchi, 2006).

The new knowledge creation is a process which comes through a constant dialogue between both tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge categories; hence, once the knowledge has been developed by individuals, it shouldn't be kept along with individuals itself. The organizations need to be proactive to articulate and amplify the individual's knowledge across the organization (Nonaka, 1994). Further, rapid technological development, frequent changes in the business environment, and overflow of compactors' entrance to the market, eventually get products obsolete, perhaps over nightly. The survivals were the ones who created new knowledge regularly and transmitted that knowledge across the organization quickly embodying it into new technologies and products. The whole processes define the "knowledgecreating company" which discussed how companies gain business success through continuous innovation. Moreover, the only certainty in an economy is an uncertainty, and the only certain source to gain a completive advantage is the knowledge (Nonaka, 1995). Today's organizations are competing with knowledge intensive market environment (Hunter & Scherer, 2009). Today's organization are highly dynamic, more complex and collaborative; accordingly, knowledge intensive organization are required to capitalize the both individual and collective critical knowledge through knowledgeintensive process to become a success .

5. c) Knowledge Management

The knowledge management general model (Newman & Conrad, 2000) discussed about knowledge creation, knowledge retention, knowledge transfer, knowledge utilization and gave a better understanding of knowledge flow in a firm that includes a set of processes, events, and activities. The SWISS forum building block of knowledge management (Probts, 1998) identified knowledge identification, knowledge acquisition, knowledge development, knowledge distribution, knowledge utilization, and knowledge retention as dimensions of knowledge management.

The popularity of knowledge management began in the 1990s (North & Kumta, 2018). Since then, academic interest in knowledge management is reflecting in many ways (Hislop, Bosua & Helms, 2018). Since ever, academics discussed those knowledge dimensions together with some other dimensions that effect on the performance of SMEs. Gozalez & Martins (2017) described the knowledge management process in four stages, namely knowledge acquisition stage, knowledge storage stage, knowledge distribution stage, and knowledge use stage. The knowledge inception, creative process, knowledge transformation, and organizational learning were being discussed under the knowledge acquisition stage. The knowledge storage stage covers with the organization and information technology are being described. The social contract themes, practice community, and sharing via information technology are being discussed under the distribution phase. The form of use, dynamic capacity, retrieval, and knowledge transformation are being categorized in the final stage of knowledge use.

Bagoroza (2015) argued knowledge acquisition, knowledge dissemination, responsive to the knowledge that improve performance, openness, action orientation, continues improvements, long term commitment, workforce quality, and management quality as some of the dimensions of knowledge management. Nawab, Nazir, Zahid & Fawad (2015) argued that creation, organization, storage, sharing, and utilization of knowledge are being considered as stages in the knowledge management process. Johnson (2015) found both sustainability management tools such as environmental management systems, corporate citizenship, audit, intensive system, and sustainability and knowledge management tools such as knowledge identification, knowledge acquisition, knowledge conservation, knowledge application, and knowledge retention join hands as contributory factors for performance of SMEs and those tools allow to establish sustainability knowledge into day to day routine practices in SMEs. Nawaz, & Shaukat (2014) found that knowledge acquisitions, knowledge dissemination, and responsive on knowledge have a significant effect to both innovation and financial performance.

Gholami et al. (2013) argued knowledge acquisition, knowledge storage, knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, and knowledge implementation as significant factor loadings for knowledge management. Omerzel (2010) identified knowledge use, knowledge acquisition at the individual level, knowledge store, motivation, measuring the efficiency of knowledge management implementation, and knowledge transfer, gave an impact of knowledge management and concluded that all the dimensions are interrelated and important for performance growth of SMEs.

Durst & Edvardsson (2012) argued the role of knowledge identification in achieving the productivity of SMEs despite knowledge intensity in SMEs. Egbu, Haris & Renukappa (2005) argued knowledge identification, knowledge capturing, knowledge sharing, knowledge mapping, as knowledge disseminations. Veneble & Dell (2012) argued that knowledge identification to be fixed to the mainstream agenda when formulating knowledge management strategies as it is important to continuously identify new knowledge to the firm to counter the scarcity that creates when employee leaves the firm at their retirement, in some cases premature retirements. Moreover, SMEs are often in danger of leakage (Durst & Ferenhof, 2014).

The empirical argument on knowledge management is continuing even today. Al Ahbabi, Singh, Balasubramanian & Gaur (2019) described knowledge management processes such as knowledge creation, knowledge capture, knowledge storage, knowledge sharing, knowledge application, and knowledge use have a positive and significant impact on operational, quality and innovation performance of public sector organizations. Hassan & Raziq (2019) identified knowledge management as a strategic approach that enhances the performance of SMEs. However, nearly 82 percent of SMEs are inefficient or ineffective in knowledge management tools and knowledge management practices, and only 12 per cent are succeeding in both aspects (Centobelli, Cerchione & Esposito, 2019).

Japanese companies are the frontier of knowledge management (Takeuchi, 2006). The scholars in business management pay a close interest in external knowledge acquisition over the consecutive years due to its strategic impotence. However, it was found that knowledge management faces continuous challenges. However, knowledge identification capabilities of the firm enable to accelerate the amount of acquired knowledge. Accordingly, firms which understood how knowledge available is embodied within interorganizational network comparatively can develop new strategies to acquire that institutional knowledge; thereby, integrate those knowledge categories with exiting knowledge base either current of future use (Ortiz, Donate & Guadamillas, 2017). The knowledgebased leadership through innovations which has a positive relationship with knowledge management practices, and those effective knowledge management practices will enhance business performance (Sadeghi & Rad, 2018).

6. III.

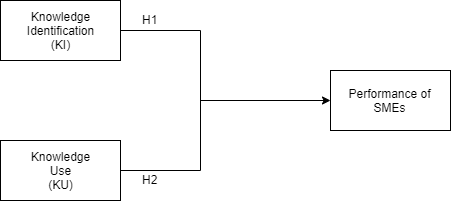

7. Conceptual Framework

8. b) Methodology

The proposed study is exploratory research with the objective of the understanding relationship of knowledge identification and knowledge use on the performance of apparel SMEs in Sri Lanka. Primary data were gathered, at once, through a self-administrated questionnaire, and a simple random sampling technique was used to select the sample population, which included owners of apparel SMEs, as respondents. As per the export performance indicators of Sri Lanka published by Sri Lanka Export Development Board, as of 2017, the population of 402 export-oriented apparel SMEs were being identified and out of which 235 samples were taken (Krejcie and Morgan, 1970). The gartered data were statistically analyzed through SPSS 21 version to generate results.

9. IV.

Analytical Techniques To determine the appropriateness of factor analysis, KMO to be read as 0.60 minimum (Pallant, 2007). The KMO values are over 0.7,which is considered to be middling. This indicates that the distribution of values is adequate for conducting factor analysis (Kaiser, 1974). The probability of the Bartlett Test of Sphericity to be significant, P-value should be less than 0.05. Hence, factor analysis can be carried out to determine the factor loading (Pallant, 2007); as the results are highly significant for both variables of knowledge identification and knowledge use, data do not produce an identity matrix and thus approximately multivariate normal. The variance extracted by each factor is represented by explained variance.

As the data have internal consistency and adequacy, mean values of the corresponding number of items to operationalize variables were computed, and then other analyses was carried out to address research objectives. Table 4.3 provides the results of the descriptive statistics in line with the first research objective. The first research objective is expected to explain the nature of responses about knowledge identification, knowledge use on the performance of apparel SMEs. Based on the results of descriptive statistics, all the mean values consist of Likert scale values are around 4. This represents agreed level responses to the knowledge identification, knowledge use, and performance of apparel SMEs. Meaning, owners of apparel SMEs in Sri Lanka are practicing both knowledge identification and knowledge use at workplace of SMEs at an average level. Accordingly, these factors have positive responses in the SME sector. All the coefficient of skewness is between -2 and +2, meaning, data are normally being distributed.

The second research objective is expected to analyze the effect of knowledge identification, and knowledge use on performance of apparel Small and Medium-scaled Enterprises and multiple regression model was being used to analyze the effect. Table 4.4 provides the results of the regression ANOVA. Probability of F-test statistics is significant as the P-value is 0.000. This indicates that knowledge identification and knowledge use jointly influence on the performance of apparel SMEs. As the model is jointly significant, the leaner regression model is appropriate.

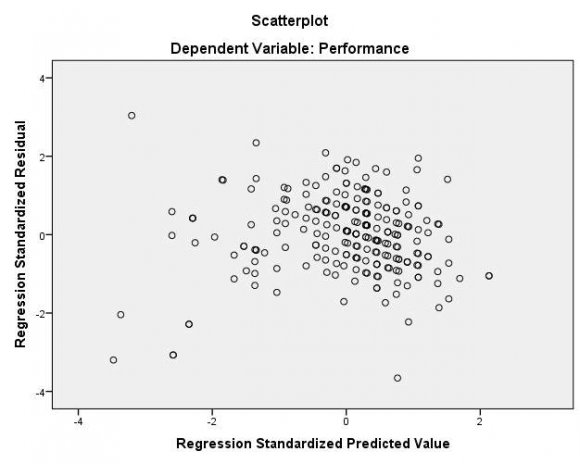

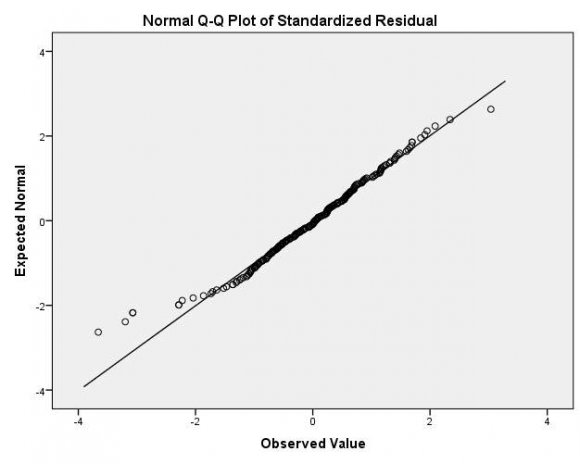

Durbin-Watson test statistics is 1.92. This is between 1.5 to 2.5. This represents that residuals are independent. Table 4.5 is providing individual effect of knowledge identification and knowledge use on the performance of apparel SMEs. The probabilities of knowledge identification and knowledge use are respectively 0.000 and 0.008. Both of these probabilities are highly significant at 1%. Therefore, knowledge identification and knowledge use individually influence on the performance of apparel SMEs. Their Beta values are respectively 0.274 and 0.129. Results indicate that knowledge identification and knowledge use significantly positively influence on the performance of apparel SMEs. According to the standardized coefficient of Beta, knowledge identification is the most influential factor as it comprises the highest standardized coefficient of Beta. Accordingly, research hypotheses one and two are accepted. According to the collinearity statistics, the VIF value is 1.2. Therefore, knowledge identification and knowledge use are not perfectly correlated. This means that no Multicollinearity problem. Figure 1 presents the behavior of standardized residuals. V.

10. Discussion and Conclusion

The findings of the study highlighted that both knowledge identification and knowledge use are in existence at apparel SMEs in Sri Lanka at an average level, meaning, owners of those apparel SMEs are getting benefit out of those knowledge management practices while practicing at the workplace (Table 4.

11. 3).

As the first research objective was to determine the nature of knowledge identification and knowledge use on the performance of apparel Small and Mediumscaled Enterprises, the finding is being addressed to the first research objective. The results further highlighted that knowledge identification and knowledge use are having significantly positively influence on the performance of apparel SMEs, jointly (Table 4.4). Although, both knowledge identification and knowledge use significantly positively influence on performance of apparel SMEs, knowledge identification was the most influential factor on the performance of apparel SMEs as per the results indicated in Table 4.5 and outcome of those findings are addressed to the second research objective which was focused on analyzing the effect of knowledge identification and knowledge use on performance of apparel Small and Medium -scaled Enterprises.

The outcomes of research objectives were further endorsed with the acceptance of research hypothesizes. The summary of the research hypothesis is being given in Table 5.1. The findings of the study are further supported with the previous studies done by Gozalez & Martins, 2017;Nawab et al., 2015;Gourva, 2010;Evangelista et al., 2010;Evangelista et al., 2010;Nonaka, 1995;Probts, 1998;Desouza & Awazu, 2006) using the bothknowledge identification and knowledge use. It was evident to prove that both dimensions are in existence at SMEs as part of the knowledge management process in achieving performance. Therefore, the findings of the study could be useful to owners of apparel SMEs to use identified new knowledge to achieve performance success. As there were limited studies in this area (Tow & Kim, 2017), the findings could also be considered as an additional empirical contribution to narrow the existing literature gap.

The study has its limitations, like many other studies, which allow further research. First, the study was limited to export-oriented owners of apparel SMEs as the respondents instead of taking owners of other export categories. The cross-sectional nature of the study prevented to carry out data collection from the respondents on repetitive occasions. Secondly, study was only to establish relationship of two dimensions of knowledge management where previous studies were done taking other dimensions of knowledge management towards performance of SMEs (Al Ahbabi Gholami et al., 2013;Omerzel, 2010). Accordingly, the study leaves to carry out further studies on how knowledge development and knowledge retention establish a relationship on the performance of SMEs because Probst (1998) identified both of them as some of the dimensions of knowledge management.

12. Références

| 3) Multiple regression analysis for 2nd research | |||||

| objective | |||||

| a) Reliability Analysis | |||||

| Reliability analysis has been carried out to | |||||

| determine internal consistency. | |||||

| The formula is being given by Eq.01 | |||||

| ?=????1?(1+??)???????????.01 | |||||

| Where: | |||||

| r: Average inter-item correlation pair-wise | |||||

| k: Number of items in the scale. | |||||

| The researcher initially tested internal | |||||

| consistency of Likert scale items before variables are | |||||

| operationalized. The direction of responses has been | |||||

| determined in this analysis to study uni-dimension. | |||||

| Researcher applied Cronbach's Alpha, and results are | |||||

| being provided by table 4.1. | |||||

| 1) Reliability Analysis | |||||

| 2) Descriptive Statistics for 1st research objective | |||||

| Cronbach's Alpha value represents reliability. Al | conducted through factor analysis, incorporating two | ||||

| the Cronbach's values of the Pilot test are over 0.7, | statistical measures, namely; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), | ||||

| which is accepted (Hinton et al., 2004; Hair et al., 2010; | the measure of sampling adequacy, and Bartlett's Test | ||||

| Peterson, 1994). | of Sphericity. The results are provided by table 4.2. | ||||

| To | determine | the | appropriateness | of | |

| measurable items used in the study, a validity test was | |||||

| Variables | Cronbach's Alpha Number of Items | |||

| Knowledge Identification | 0.709 | 7 | ||

| Knowledge Use | 0.705 | 7 | ||

| Performance | 0.704 | 14 | ||

| Variables | KMO Bartlett's Chi-Square Bartlett's P Value Explained Variance | |||

| Knowledge Identification | 0.720 | 325.6 | 0 | 52.06 |

| Knowledge Use | 0.747 | 237.6 | 0 | 36.29 |

| Performance | 0.705 | 579.3 | 0 | 57.31 |

| Measures | Identification | Use | Performance |

| Mean | 4.2790 | 4.2991 | 4.2629 |

| Std. Deviation | .36654 | .35290 | .26600 |

| Skewness | -1.145 | -.714 | -1.267 |

| Std. Error of Skewness | .159 | .159 | .159 |

| Kurtosis | 1.930 | .434 | 3.671 |

| Std. Error of Kurtosis | .316 | .316 | .316 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 Regression | 3.748 | 2 | 1.874 | 33.940 .000 | 1.921 | |

| Residual | 12.809 | 232 | .055 | |||

| Total | 16.556 | 234 | ||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | ||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 2.535 | .218 | 11.624 | .000 | |||

| Identification | .274 | .046 | .378 | 5.938 | .000 | .824 | 1.214 | |

| Use | .129 | .048 | .171 | 2.689 | .008 | .824 | 1.214 | |

| F | igure 3: |