1. I. Introduction

ighlighting the importance of Business Incubators (BIs) researchers (Berget and Norrman, 2008;Allen and Rehman, 1985;Gribaldi and Grandi, 2005;Ratinho et al., 2010) have elaborated that BIs promote new business formation, prevent new venture failure and establish vibrant entrepreneurial sector. BIs provide an environment where public and private resources can combine to meet the needs of SMEs during their critical stages of development (Shalaby, 2009). National Incubation Association (NBIA) considered five types of BIs. These are: Mixed use-47%; Technology-37%; Manufacturing -7%; Service 6%; and Others-4% (NBIA). Others include business incubators that are for web-related business, the community revitalization program and simply other. BIs are also known with a variety of names like, "innovation center", "enterprise center," and "business and technology center" (Smilor, 1987). BIs provide an attractive framework to new entrepreneurs in dealing with problems in establishing new firm. BIs can be considered as a solution for the difficulties that small and new firms encounter and they provide business support services (Smilor, 1987;Lalkaka and Abetti, 1999). This study is focusing on Agri-business incubators.

2. II. Literature Review

Incubator studies are mainly descriptive and mostly dealing with the different concept of the business incubator and their function (e.g. Allen, 1985;Allen and Leviru;1986;Smilor and Gill, 1986). They mainly deal with the basic requirement of an incubator, like they should provide physical space, shared services, business consulting service, etc. Capital, technology talent was linked to encourage entrepreneurial talent; speed up the growth of new technology-based firms and enhance the commercialization of technology. Researchers since 1990s have begun to complete the concept by describing the role and service of business incubators, i.e. incubator hatch new ideas by providing new ventures with physical and intangible resources and speed up new ventures establishment and increase their chance of success (Tang, Baskaran, Pancholi & Muchie, 2011).

Von Zedtwitz and Grimaldi (2006) describe incubators as that which help the entrepreneur to develop business and marketing plans, built management teams, obtain venture capital and provide access to professional and administrative services. Counseling interaction with incubator management help ventures to gain business assistance whereas networking with incubator management help ventures to access technical assistance (Seillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). Matt and Tang (2010) state that the perceptions and concepts of business incubator have evolved over the period from the initial focus on physical space with basic facilities to value-added services and systematic incubation process. Networking is very pertinent in this Year ( ) A age of competition. Elaborating networking element of BIs, Seillitoe and Chakrabarti (2010) opined that counseling interaction with incubator management help ventures to gain business assistance, while networking with incubator management help ventures to access technical requirements.

Most small businesses fail within their five years of operation due to shortage of capital and lack of proper management skills; incubator facilities provide an environment where public and private resources can combine to meet the needs of small business during their critical stages of development (Shalaby, 2009).

The literature on incubators has been broadly classified into two categories. First, those studies that cover the theory and model related to BIs. How incubators are formed, their aim, planning and management was dealt by these researches (e.g. Allen andMc Cluskey 1990, Aeroudt, 2004;Becker and Gassmann, 2006). The second categories of studies try to evaluate incubators on certain factors that define the success indicators.

The requirement of successful incubation is the matter of research for many scholars, each giving their own set of critical success factors. Semih Adlcomak (2009) identified eight points for successful incubation. Rustam Lalkaka (2000) identified ten measures to improve the performance of incubator, are those which address the deficiencies. Seven points have been considered as key to success of a business incubator by Stephanie Pals (2006). Different studies have stated different critical success factors, but broadly they have a unified approach, and there are similarities. Kumar and Ravindran (2012) considered four factors to evaluate the performance of the incubators; they are occupancy level, sustainability, number of tenant firms in thousand sq. ft. and survival rate.

The current study evaluates the influence of two factors, i.e., Entry and Exit policy of the business incubators and Ties with University and tries to explain the impact of these factors on the outcome of the incubation. The available literature on incubation has stated in detail about the importance of these two factors in determining the successful outcome of the process.

Smilor (1987) recommends that any business incubator which tries to build companies should have a selection process which helps to evaluate, recommends and select the new tenant. Many studies conclude that there is a positive association between the existence of a clear criteria for selection and entry with the success of the incubator (e.g. Hackett and Dilts, 2004b;Totterman and Sten, 2005;Pals, 2006). Akcomak (2009) stated that any business incubator should set a selection and exit criteria. Some researchers have advocated a selection committee which would choose the new tenant companies. Tenant companies should give both an oral and written showcase of their company to the committee of whoever is deciding within the particular business incubator (Pals, 2006). The selection committee should have the sophisticated understanding of the new venture formation process and the market they will operate. This will help the decision makers to identify the "weak but promising" firm and avoid those that cannot be supported as well as those who do not require incubation . According to Berget and Norrman (2008), most of the incubators either focused on the idea or the entrepreneurial team. It's the ability and efficiency of the incubator's managerial team which decides the path that an incubator will choose while selecting tenant firm.

3. a) Entry & Exit Policy

Researchers also agree that the business incubator should have a clear policy regarding the tenure for which a tenant firm should stay in the incubator. The existence of a clear and transparent exit policy helps to use their resources appropriately. As per NBIA, the average incubation cycle times are between two and three years. Acceptance by a business incubator provided credibility to a new firm but in the long run, moving out of the incubation facility is a must for further growth . While analyzing the problems faced by the business incubators in China and Nigeria, it was found that the problem is exacerbated because the tenant firms tend to stay within the business incubator's premises even after the period expires (Ackomak, 2009). Though they provide a secure environment but to develop they should move out and face the real competition after a certain period.

4. b) Ties with University

The technical university and research institutes form the knowledge base for the creation and growth of technical skills and innovation. The association between technical university and institutes with that of business incubators provides the latter information, technology, and training required for the formation of the new business entity (Lalkaka, 2002). Many studies advocates ties with a local university and extremely beneficial to any business incubator (Pals 2006). Having ties with university gives a business incubator access to laboratory space they may not have had otherwise and thereby saves money. Collaboration with a technical university is extremely beneficial for any business incubators as advocated by several studies (Pals 2006). Having ties with university gives a business incubator access to laboratory space they may not have had otherwise and thereby saves money. Lakaka (2002) advocates that there is significant potential for synergies between technology-based incubators, a recognized technical university or research institute. Though there can be conflicts between these two entities as the set purpose of a business incubator and a university is different. Still both can work together for goals (Lalkaka and Bishop, 1995). Studies reveal that most of the successful business incubators are linked with some well-known technical universities or with some reputed research institutes. A technical university or research institute not only becomes the source of new technology but also the source of new entrepreneurs for the business incubator (Pals, 2006).

5. Items of Tie

Ties with University had seven factors. These include: 2CSF1: advocating ties of business incubators with Universities; 2CSF2: access to potential new tenant companies; 2CSF33: increased level of credibility for the business incubator; 2CSF34: access to laboratory space; 2CSF5: getting new technologies; 2CSF6: getting new business ideas; and 2CSF7: enhancing the incubation centre's probability of getting external (public or private) finance.

6. c) BI Performance

The scale items for BI Performance about above explanation and as used in the current study are: (Mian, 1997) iii BIs Financial Viability (Lalkaka, 2002) For all the three items of BI performance, managers were asked to rate these on a scale of 1-5.

Stephanie Pals, 2006 andMian (1997) highlighted the importance of BI Profitability for BI performance.

Stephanie Pals (2006) and Mian (1997) highlighted that for measuring the performance of BI, productivity can be used. BIs Financial Viability is indicator suggested by Lalkaka (2002). Thus these three were used in the study for measuring BI performance.

EFA was conducted on six success factors identified through literature. The first success factor identified and tested is the entry and exit policy. Table 2 depicts the factors related to Entry and Exit policy. Seven items converged to three, viz. i) EE11: Applicant's proposal potentiality; ii) EE12: Admission & Graduation policy; and iii) EE13: Post incubation scenario. These three factors explained 81.378 percent of the variance.

In this study, we theorize that the outcome of BI performance varies significantly with Entry and Exit policy and ties with University.

7. III. Research Design & Methodology

The present study used a structured questionnaire for collecting data from the incubators. The respondents were chosen from BI Managers and the managing staffs. The five-point Likert scale was used and, it contains seventeen questions dealing with different aspects of the study. In addition to these, there were few more to collect general information about the BIs about the type of BI; Number of tenant firms admitted scenario, the present status of the number of firms and number of graduating firms. Data were collected from 60 BIs. It is pertinent to know the reliability of Questionnaire. It is shown in Table 1. Entry and Exit Policy had seven items, and Cronbach alpha is 0.730, and for Business Incubation Performance it was 0.703. .000

From the three items that loaded on EE11: Applicant's proposal potentiality, review of the application by the incubator staff member got highest factor loading (0.939). This was followed by a review of the tenant product marketability by the incubator staff (0.933). The second component was EE12: Admission & Graduation policy. A formal rule for the graduation of the tenant (0.905) emerged as a key item in this component. In EE13: Post-incubation scenario, EE7: Suitable space is available to tenant companies outside the incubator after graduation had higher loading. All items in this factor had loadings greater than 0.70 and thus all items were retained for further analysis.

Ties with University had seven factors. These include: TU 21: advocating bonds of business incubators with Universities; TU22: access to potential new tenant companies; TU23: increased level of credibility for the business incubator; TU24: access to laboratory space; U25: getting new technologies; TU26: getting new business ideas; and TU27: enhancing the incubation centre's probability of getting external (public or private) finance.

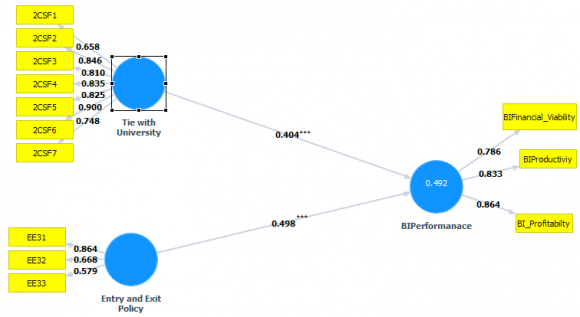

In case of ties with university TU26: getting new business ideas loaded heavily. TU22: access to potential new tenant companies was next to it; TU24: access to laboratory space; U25: receiving new technologies. Figure 1 and Table 6 shows the results of SEM-PLS. The next objective was to find the relationship between Entry and Exit policy factors and BI performance. The results suggest that Beta values for Entry and Exit policy factor are 0.498 (-value: 4.628). Thus this emerges as a significant predictor of BI Performance. The last objective was to find the relationship between ties with University and BI performance. Beta values for ties with University are 0.404 (t-value: 3.214). Hence, this is also critical success factor (CSF) for gauging Business Incubation Performance. Relationship, Collaboration and alliance with university are essential and extremely advantageous for any business incubators (Pals 2006;Lalkaka, 2002). Thus, this is supported by the literature. The importance of Entry and Exit policy has been advocated by Akcomak (2009), focusing on a clear Entry and Exit policy and for providing assistance to tenant companies (Lalkaka, 200;Totterman and Sten, 2005;Pals, 2006;Mian, 1994). This study has been one of initial studies on understanding whether clear Entry and Exit policy and ties with universities can help in improving the BI performance. To sustain BI performance these two critical success factors can play a dominant role in the survival and sustenance of BIs.

8. Year ( )

| Items of Critical Success Factor | References |

| EE1: The incubation centre has a formal policy for admitting tenant companies to the Incubator. | Smilor,1987; Hackett and Dilts, 2004 |

| EE2: The decision process begins with a staff review of applicant's growth potential. | Hackett and Dilts, 2004;Totterman and Sten, 2005; Pals, 2006 |

| EE3: The decision process includes a staff review of | Smilor,1987; Hackett and Dilts, 2004;Totterman and Sten, |

| applicant's Product Marketability. | 2005; Pals, 2006 |

| EE4: The decision process begins with a staff review of applicant's Application of new technologies. | Totterman and Sten, 2005; Pals, 2006 |

| S. No. | Construct | No. of Items | Cronbach's Alpha |

| 1. | Entry and Exit Policy | 7 | 0.730 |

| 2. | Ties with University | 7 | 0. |

| 3. | Business Incubation Performance | 3 | 0.703 |

| a) Objectives of the Study | IV. Data Analysis | ||

| Following are objectives of the present study: O1: O2: To find the relationship between entry and Exit | As shown through table 3, Entry and Exit items converged into three factors, viz. EE11: Applicant's proposal potentiality; EE12: Admission & Graduation | ||

| policy factors and BI performance. | policy; and EE13: Post incubation scenario. These three | ||

| O3: To find the relationship between ties with University | factors explained 81.378 % of the variation. | ||

| and BI performance. | |||

| ***p<.001 |

| BI Performance | Entry and Exit Policy | Ties with University | |

| 2CSF1 | 0.658 | ||

| 2CSF2 | 0.846 | ||

| 2CSF3 | 0.810 | ||

| 2CSF4 | 0.835 | ||

| 2CSF5 | 0.825 | ||

| 2CSF6 | 0.900 | ||

| 2CSF7 | 0.748 | ||

| BI Financial Viability | 0.786 | ||

| BI Productivity | 0.833 | ||

| BI Profitability | 0.864 | ||

| EE31 | 0.864 | ||

| EE32 | 0.668 | ||

| EE33 | 0.579 | ||

| AVE | 0.686 | 0.509 | 0.651 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.867 | 0.752 | 0.928 |

| Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for BI | larger than the threshold value of 0.70. Thus it is | ||

| Performance; Entry and Exit Policy; and Ties with | acceptable to proceed ahead with the analysis. | ||

| University is more than the threshold level of 0.50. | Table 4 gives Fornell -Larcker Criterion | ||

| Composite Reliability is greater than 0.70 and is 0.867 | Discriminant Validity. As the results indicate discriminant | ||

| for BI Performance; 0.752 for Entry and Exit Policy; and | validity is fine. | ||

| 0.928 for Ties with University. Composite Reliability is | |||

| BI Performance | Entry and Exit Policy | Tie with University | |

| BI Performance | 0.828 | ||

| Entry and Exit Policy | 0.579 | 0.714 | |

| Tie with University | 0.504 | 0.201 | 0.807 |

| Table 5 reflects the Variance Inflation Factor | |||

| (VIF). As the VIF values are less than threshold value | |||

| of 5, thus we proceeded to perform SEM-PLS. | |||

| © 2018 Global Journals | |||

| Inner VIF | BI Performance |

| BI Performance | |

| Entry and Exit Policy | 1.042 |

| Tie with University | 1.042 |

| Outer VIF | |

| 2CSF1 | 2.073 |

| 2CSF2 | 3.944 |

| 2CSF3 | 3.811 |

| 2CSF4 | 2.931 |

| 2CSF5 | 4.560 |

| 2CSF6 | 4.737 |

| 2CSF7 | 1.992 |

| BI Financial Viability | 1.440 |

| BI Productivity | 1.643 |

| BI Profitability | 1.779 |

| EE31 | 1.233 |

| EE32 | 1.213 |

| EE33 | 1.061 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Error (STERR) | T Statistics (|O/STERR|) | P Values | |

| Entry and Exit Policy -> BI Performance | 0.498 | 0.498 | 0.108 | 4.628 | 0.000*** |

| Ties with University -> BI Performance | 0.404 | 0.416 | 0.126 | 3.214 | 0.001*** |

| R Squared | 0.492 | ||||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.474 | ||||

| V. Conclusion |