1. Introduction

rganizations generally look forward to all issues that will help in achieving organizational goals. The most important of these issues are employee-based issues, such as improvement of employee job performance through human resources management practices, particularly high-performance human resources. Some studies have confirmed a positive relationship between high-performance human resource practices and improved levels of employee's performance (Al-Hawary & Shdefat, 2016). However, there are some other factors that may have an impact in this relationship such as affective commitment Author: Researcher Amman, Jordan. e-mail: [email protected] (Al-Hawary & Alajmi, 2017). This was the reason that necessitated the exploration of the impact of human resources practices on job performance, as well as the investigation of the mediating role of affective commitment in the relationship between these two variables.

Many advantages of high-performance human resource practices were reported in the literature, such as enhancing the effectiveness of organization's activities (Daspit et al., 2018), developing employees' knowledge, skills and abilities (Kooij and Boon, 2018;Al-Hawary, 2015), empowering and motivating employees (Combs et al., 2006and Glaister et al., 2018). Examples of these practices incorporate employee selection and hiring, performance appraisal, intensive training, performance-based promotion, and incentives (Daspit et al. (2018;Al-Hawary, 2011), performance appraisal and information sharing (Kooij and Boon, 2018). The effect of high-performance human resource practices on job performance was clarified in the literature. Some of the studies found a positive effect of high-performance HR practices on job performance (Alfes et al. (2013) while other studies demonstrated a negative effect of high-performance HR practices such as performance appraisal, career advice, information sharing, opportunities to give ideason job performance (Kooij et al., 2013). Job performance as a construct that contribute to organizational goals (Rich et al., 2010) was divided into two types: in-role performance and innovative performance (Dizgah et al., 2012). In-role performance was regarded as a variable associated to job. Therefore, it can be used by job performance and employee ability to meet the requirements of performance. Innovative performance, on the other hand, refers to employee ability to generate, promote and realize ideas (Turnley and Feldman, 2000and Somech, 2006, Lee et al., 2010, Schreurs et al, 2012).

Three common components of organizational commitment were introduced in the literature: affective, continuous, and normative commitment (Meyer and Allen, 1991). Affective or emotional commitment refers to employee attachment to the organization. Continuous commitments describes a state of comparison in which an employee distinguishes between costs caused by his or her decision to leave or stay with the organization, while normative commitment explains employee decision to stay with the organization (Kim andBeehr, 2018, Ramalho Luz et al., 2018). Studies that investigated relationships between high-performance human resource practices and affective commitment provide an evidence on positive relationships between these variables (Al-Hawary and Alajmi, 2017 and Kooij and Boon, 2018).With reference to the relationship between affective performance and job performance, numerous studies reported such a relationship (Shore and Wayne, 1993, Vandenberghe et al., 2004, Khan et al., 2010). In order to gain more understanding on the effects of high-performance HR practices on job performance in the presence of affective commitment as a mediator, this study was conducted to instruct practitioners to consider affective commitment to enhance the influence of HR practices on job performance.

2. II.

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development a) High performance HR practices

High-performance human resource practices was defined as a set of practices that have a vital effect on the effectiveness of the organization's activities (Daspit et al., 2018). Reviewing Kooij and Boon's (2018) study, this term can be defined as a bundle of practices used to manage human resources by focusing on three aspects related to employees' ability, motivation, and participation.

From strategic human resource management theorists, high-performance human resource practices were considered as performance improving practices. The main cause behind regarding these practices as performance elevator was the ability of such practices to equip employees with three essentials, i.e., to enhance employees' skills, knowledge and abilities, to empower employees to do their jobs, and to keep them motivated (Combs et al., 2006). In the same context, Glaister et al. (2018) regarded high performance HR practices as practices used in organization to enhance employees' skills, employees' motivation and to enhance opportunities provided to them to use their skills and to benefit from their motivations.

Research on human resource practices in general resulted in numerous dimensions of highperformance human resource practices. Daspit et al. (2018) used five dimensions of high performance HR practices which were: employee selection and hiring, performance appraisal, intensive training, performancebased promotion, and incentives. In their study on a sample consisted of employees selected from Dutch university to investigate the relationship between high performance HR practices and affective commitment, Kooij and Boon (2018) categorized these practices into three main categories: practices that have an effect on employees' abilities such as training, practice that have influence on employees' motivations like performance appraisal, and employees' participation such as information sharing. Combs et al. (2006) and Kehoe and Wright (2013) intimated three classes of high-performance human resource practices, which were practices that enhance employees' knowledge, skills and abilities, practices that magnify employees' motivation and practices that heighten empowerment. Table 1 presented high-performance human resource practices used in the current study. Those variables were utilized due to their association between both employees and the organization. These practices have a positive of employees' job achievement in an effective manner and, on the other hand, have a positive effect on the organizational performance (Wright et al., 2005). 2). According to them, in-role performance is the dimension that constitute employee's tasks and responsibilities reported in the job description, while innovative performance is the dimensions that represent the innovative ideas or solutions provided by an employee to cope with problems faced in the work environment. Janssen (2001) assessed in-role performance using three sub-dimensions: job description, employee's responsibilities, and performance requirements and evaluated innovative performance applying three subdimensions: idea generation, idea promotion and idea realization. The same latent and observed variables of job performance were wielded in research (Turnley andFeldman, 2000, Somech, 2006

? Innovative performance

? Idea generation ? Idea promotion ? Idea realization c) Affective commitmentIn their model of organizational commitment, Meyer and Allen (1991) conceptualized this variable into three components: affective commitment, instrumental commitment and normative commitment. These three components identified three states by which employee behavior in relation to the organization can be described. Employee attachment to his or her organization refers to affective commitment, employee perception of the cost he or she incurred in case of leaving the organization describes the instrumental commitment, while employee will to stay in the organization characterizes the normative commitment. According to Ramalho Luz et al. ( 2018), affective commitment is the most prevalent component of organizational commitment in the related literature. Kim and Beehr (2018) added that affective commitment is the component that built on the emotional attachment between the employee and the organization in comparison with instrumental and normative commitment that developed based on tangible causes. Therefore, attachment commitment was used in the current study. Allen and Meyer (1990) defined the affective commitment in terms of employee's identification with the organization, employee's emotional attachment to the organization and employee's involvement in the organization.

4. d) Research hypotheses i. High performance HR practices and job performance

The positive influence of high performance HR practices on job performance was highlighted in numerous previous studies. Kooij et al. (2013) investigated relationships between HR practices, employee well-being (organizational commitment, organizational fairness and job satisfaction) as well as employee performance. They analyzed three sets of HR practices: development HR practices (training, a challenging job and full utilization of training outcomes), maintenance HR practices (performance appraisal, career advice, information sharing, opportunities to give ideas) and job enrichment HR practices. The results pointed out a negative correlation between development HR practices and employee job performance, and positive correlations between maintenance HR practices and job enrichment HR practices and job performance. Measuring job performance by task performance and innovative work behavior, Alfes et al. (2013) supported the hypotheses that high-performance HR practices are positively related to job performance. Based on these results, the following hypotheses was proposed: H1: High performance HR practices has a positive influence on in-role job performance. H2: High performance HR practices has a positive influence on innovative job performance.

ii. High performance HR practices and affective commitment Al-Hawary and Alajmi (2017) examined the impact of human resource management practices (human resource planning, recruitment and selection, rewards and incentives, and performance appraisal) on organizational commitment (affective, normative and continuance commitment). Their results underlined that human resource management practices were positively correlated to organizational commitment. Meyer and Smith (2000) examined the relationship between HR practices (performance appraisal, benefits, training, and career development) and organizational commitment (affective, normative and continuance commitment) and pointed out that HR practices have no direct effect on organizational commitment since the relationship between these variables are mediated by organizational support and procedural justice. Investigating the deferential role of affective and continuance commitment from managers' perspectives, Gong et al. (2009) found that maintenance HR practices (employment security, selective hiring, career planning and advancement, participation in decision making, performance appraisal, performance-based pay, training) have no correlation with affective commitment. The results of Kooij and Boon (2018) revealed a positive effect of high performance human resource practices on affective commitment. Consequently, the following hypothesis was offered: H3: High performance HR practices has a positive influence on affective commitment.

5. iii. Affective commitment and job performance

The evidence on the relationship between affective commitment and job performance particularly has been established in the literature. In 1989, Meyer et al. found a positive correlation between affective commitment and job performance. Shore and Wayne (1993) indicated that in-role behaviors such as performance has an effect, either positive or negative, on the organizational effectiveness. Therefore, it was acknowledged that studying commitment and examining its related behaviors is very important for academics and practitioners. Vandenberghe et al. ( 2004) make a distinction between three states of affective commitment in which an employee affectively committed to the work group, the supervisor, and the organization. Their results indicated that employee's affective commitment to the supervisor had a positive impact on job performance. Riketta (2002) showed that affective or attitudinal commitment was one of the most examined variables by researchers in the field of organizational behavior due to its effects on the positive behaviors that enhance the effectiveness of the organization itself. Khan et al. (2010) studied the relationship between organizational commitment as measured by affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment and found positive effects of these types on job performance. The findings of Somers and Birnbaum (1998) confirmed that organizational commitment (affective and continuous) has a non-significant association with job performance. According to Al-Hawary and Alajmi (2017), organizational commitment (affective, normative and continuance commitment) can be used asa predictor of job performance (human resource planning, recruitment and selection, rewards and incentives, and performance appraisal).In terms of the mediating role of affective commitment in the relationship between highperformance human resource practices and in-role or innovative job performance, there were no studies that examined these relationships. However, Ng et al. (2010) found that organizational commitment mediated the relationship between psychological contract breaches and innovative job performance. On the basis of these results, the following hypotheses were suggested: H4: Affective commitment has a positive influence on in-role job performance H5: Affective commitment has a positive influence on innovative job performance H6: Affective commitment mediates the relationship between high-performance HR practices and in-role job performance. H7: Affective commitment mediates the relationship between high-performance HR practices and innovative job performance.

6. III.

7. Research Methodology a) Research sample and data collection

A sample of 600low, middle and high levels managers and employees were selected from 10 industrial organizations located in Irbid, Jordan. Six hundred questionnaires were distributed to managers and employees in those organizations. Each organization received 60 questionnaires to be filled by 1 manager and 19 employees from each managerial level. Four hundred and sixty-eight questionnaires were returned complete, indicating a response rate of 78 percent.

8. b) Research model

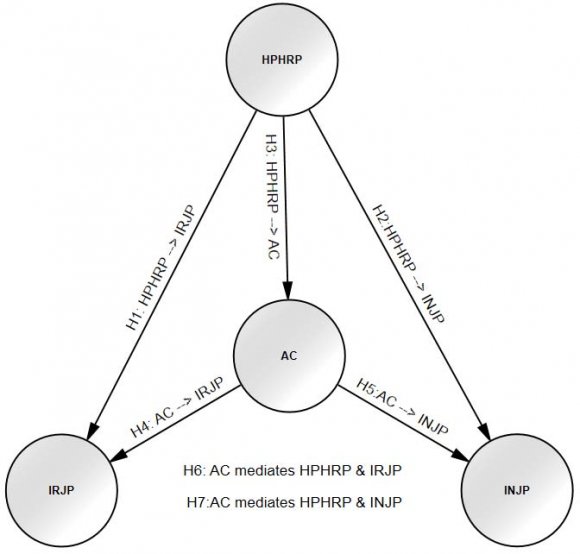

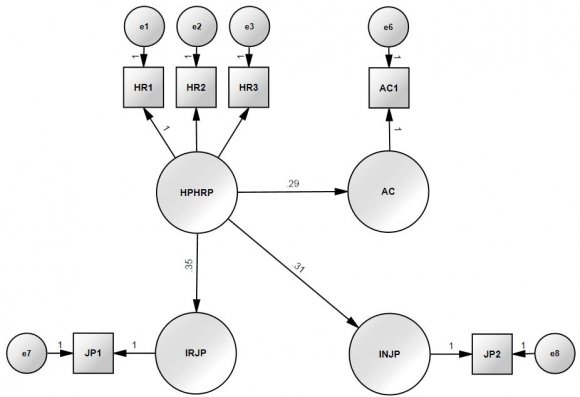

Figure 1 displays the proposed model of the current study. It included 7 hypotheses in which highperformance human resource practices was postulated to has an influences on in-role job performance, innovative job performance and affective commitment (H1, H2, H3) and affective commitment was hypothesized to has influences on in-role job performance as well as innovative job performance (H4, H5). Furthermore, affective commitment was presumed to play a mediating role in the relationship between high-performance human resource practices and in-role job performance (H6) and a mediating role in the relationship between high-performance human resource practices and innovative job performance (H7). Three key dimensions were used as dimensions of high performance human resource practices in the current research: knowledge, skills, and abilities HR practices, motivation HR practices and empowerment HR practices. Fourteen items were adopted from Gardner et al. (2001) to measure these practices. On the other hand, job performance categories, which were in-role or standard and innovative job performance, were measured using 10 items from Janssen (2001). In-role job performance items were related to job description, employees' responsibilities, employees duties, and performance requirements, while innovative job performance items were linked to idea generation, promotion and realization. Affective commitment was measured by six items from Rhoades et al. (2001). The focus of these items was on employee sense of belonging to the organization, employee attachment to the organization, employee proud of the organization, employee personal meaning of his work at the organization, and employee feeling of organization problems as it were his own problems.

IV.

9. Research Results

10. a) Data aggregation

In order to ensure homogenous responses, the required data were aggregated to the group level due to the structure of the response that were collected from both managers and employees. Chan (1998) stated that the aggregation of individual responses should be justified based on indices of within-group like R wg index that suggested by James et al. (1984( , cited in Chan, 1998)). In a similar case, the aggregation method was used by 3 that emerged on the basis of within-group agreement and ICCs made known that the evaluation of high-performance human resource practices, in-role and innovative job performance and affective commitment as group-level variables was statistically justified. Low values of ICC1 (the total variance between group members) and high levels of ICC2 (reliability index for group mean) present that the group level variable is free of rater errors (Newman and Sin, 2009). Means, standard deviations, factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), Cronbach's alpha, and composite reliability (CR) were computed and presented in Table 4. The results showed moderate to high means of respondents estimations: KSA HR practices (M = 3.62), motivation HR practices (M = 3.35), empowerment HR practices (M = 3.63), in-role performance (M = 3.61), innovative performance (M = 3.52), Affective commitment (M = 3.37). Factor loadings were ranged from 0.69 to 0.82 and indicating strong loadings since all values were higher than 0.6. Götz et al. (2010) indicated that AVE is a common measure used to test convergent validity and a value of AVE above 0.5 is well advised. A value of Cronbach's alpha above 0.7 is considered acceptable (Santos, 1999). On the other hand, composite reliability higher than 0.70 is used as a threshold point (Martensen et al., 2007).

11. c) Product moment correlation coefficients

Pearson coefficients were computed as shown in Table 5 in order to estimate the strength of the linear correlation among research variables. The results marked positive and significant associations among all variables. That is, KSA HR practices was positively correlated to motivation HR practices (r = 0.55, P < 0.05), empowerment HR practices (r = 0.48, P < 0.05), in-role job performance (r = 0.71, P < 0.05), innovative job performance (r = 0.50, P < 0.05) and affective commitment (r = 0.39, P < 0.05). Motivation HR practices was positively correlated to empowerment HR practices (r = 0.40, P < 0.05), in-role job performance (r = 0.69, P < 0.05), innovative job performance (r = 0.73, P < 0.05) and affective commitment (r = 0.57, P < 0.05).

Empowerment HR practices was positively correlated to inrole job performance (r = 0.63, P < 0.05), innovative job performance (r = 0.78, P < 0.05) and affective commitment (r = 0.68, P < 0.01).In-role job performance was positively correlated to innovative job performance (r = 0.60, P < 0.01) and affective commitment (r = 0.66, P < 0.05). Finally, the results treasured a positive association between innovative job performance and affective commitment.

12. d) Structural equation modeling (SEM)

Structural equation Modelling (SEM) has been emerged as a statistical methodology used to test hypotheses. According to this methodology, the variables of the proposed model are tested simultaneously to determine the degree of model consistency with data. A good fit model presents an acceptance of the hypothesized relationships among variables. If not, such relationships should be rejected (Byrne, 2016). The hypothesized model of this study comprised seven relationships among variables. Highperformance HR practices (KSA HR practices, motivation HR practices and empowerment HR practices) were postulated to have positive effects on job performance (in-role and innovative job performance) and affective commitment (AC). Furthermore, positive effects were assumed between affective commitment and in-role and innovative job performance. Due to the presence of affective commitment in the model as a mediator variable, two hypotheses were presuppose in relation to the mediating role of high-performance HR practices and job performance (in-role and innovative job performance).

13. e) Goodness-of-fit

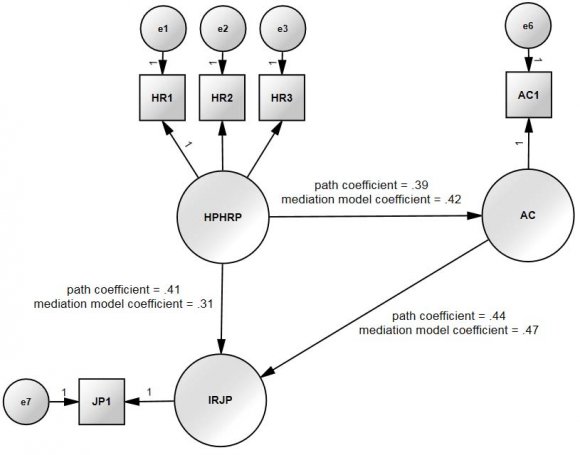

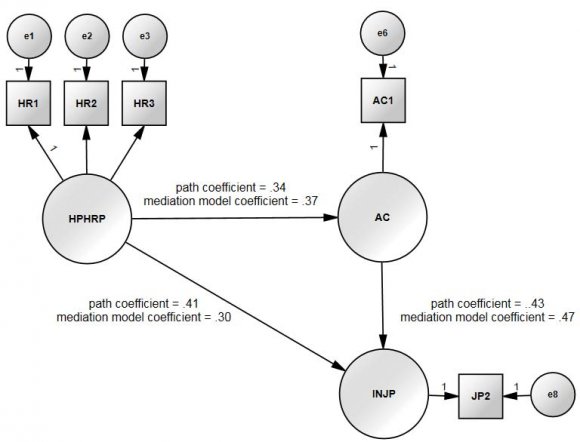

Five indexes were used to test goodness-of-fit: the minimum discrepancy (Chi-square/degrees of freedom), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), The comparative fit index CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The results given in Table 6 demonstrated a good fit model. Thereupon, the model cab be used to test the hypotheses. The results in Figure 3 affirmed that AC mediated the effect of high-performance HR practices on in-role job performance (path coefficient = 0.41, P < 0.05, mediation model coefficient = 0.31, p > 0.05). In relation to innovative job performance, the results in Figure 4reasserted that affective commitment partially mediated the effect of high-performance HR practices on innovative job performance. In that event, hypotheses 4, 5, 6, and 7 were accepted.

14. Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of this study was twofold. First, to explore the impact of high performance HR practices and job performance as divided into two types: in-role job performance and innovative job performance. Second, to examine the mediating role of affective commitment in the effect of high performance HR practices and in-role job performance as well as innovative job performance. Unlike Kooij et al. (2013), the results of this study pointed out that high performance HR practices positively affected both in-role job performance and innovative job performance. A similar result was found by Alfes et al. (2013).The impact of high performance HR practices job performance was justified in the literature. Combs et al. (2006) indicated that the importance of high-performance HR practices can distinguished by the ability to improve employees' skills, knowledge, abilities, empower them to perform their tasks and to motivate them to ensure their continuity in utilizing their skills, knowledge, abilities in their jobs. Furthermore, the results of this study established a positive impact of high-performance HR practices on affective commitment. Different results were found in the literature. Al-Hawary and Alajmi (2017) and Kooij and Boon (2018) specified a positive impact of HR practices on organizational commitment as measured by affective, normative and continuance commitment, while Meyer and Smith (2000) reported a non-significant impact of HR practices on organizational commitment (affective, normative and continuance commitment). Gong et al. (2009) showed that HR practices such as employment security, selective hiring, career planning and advancement, participation in decision making, performance appraisal, performance-based pay, and training have no correlation with affective commitment. In regard to the impact of affective commitment on job performance, it was became evident according to the present study that affective commitment has a positive impact on job performance. The result was echoed by Meyer et al. (1989) and Al-Hawary and Alajmi (2017). The findings of Somers and Birnbaum (1998) showed a nonsignificant association between affective commitment and job performance. Finally, it was became known that affective commitment play a significant role in mediating the effect of high-performance HR practices on both in-role job performance and innovative performance. To the best of the researcher knowledge, no studies were conducted to examine the same hypotheses of affective commitment mediation.

In their model of organizational commitment, Meyer and Allen (1991) conceptualized this variable into three components: affective commitment, instrumental commitment and normative commitment. These three components identified three states by which employee behavior in relation to the organization can be described. Employee attachment to his or her organization refers to affective commitment, employee perception of the cost he or she incurred in case of leaving the organization describes the instrumental commitment, while employee will to stay in the organization characterizes the normative commitment. According to Ramalho Luz et al. (2018), affective commitment is the most prevalent component of organizational commitment in the related literature. Kim and Beehr (2018) added that affective commitment is the component that built on the emotional attachment between the employee and the organization in comparison with instrumental and normative commitment that developed based on tangible causes. Therefore, attachment commitment was used in the current study. Allen and Meyer (1990) defined the affective commitment in terms of employee's identification with the organization, employee's emotional attachment to the organization and employee's involvement in the organization. The significant mediating role of affective commitment in this study can be attributed to the nature of this component which refers to the emotional attachment of an employee to his or her organization (Meyer and Allen, 1991). Decisively, it was concluded that emotionally attached employees have higher level of task-related performance as well as his desire to generate, promote and realize ideas.

15. VI.

16. Limitations and Future Research

The major limitation of this study was the lack of theoretical foundation on some variables and relationships with variables like the mediating role of affective commitment studied in this study. In a study taken place by Kooij et al. (2013), the age of the employee was found to has a significant role in relationships between human resource practices, organizational commitment and employee performance. Their results indicated that associations among these variables change in favor of employee age. Therefore, future research should consider employee age either as control or moderating variable when examining relationships among these variables.

| Dimensions | Sub-dimensions | Source | ||||

| ? | Practices | enhance | ? | Training and development | ||

| employees' knowledge, | ? | Job design | ||||

| skills, | and | abilities | ? | Compensation-oriented | KSAs | |

| (KSAs) | development | |||||

| ? | Practices | enhance | ? | Performance appraisal | ||

| employees' motivation | ? | Performance-based promotion | ||||

| ? | Incentives and rewards | |||||

| ? | Practices | enhance | ? | Information sharing | ||

| employees' | ? | Workforce planning | ||||

| empowerment | ? | Employment security | ||||

| ? | Participation programs | |||||

| ? | Self-managed teams | |||||

| Hagedoorn and Cloodt (2003) reported three | |||||||

| measurements of innovative performance, which were | |||||||

| research | and | development, | patents | and | |||

| announcements of new products. | |||||||

| Dimensions | Sub-dimensions | Source | |||||

| ? | In-role performance | ? | Job performance | Turnley and Feldman (2000), | |||

| ? | Employee responsibilities | Somech(2006), | |||||

| ? | Performance requirements | ||||||

| Variables | Rwg | ICC1 | ICC2 |

| High-performance human resource practices | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.91 |

| In-role and innovative job performance | 0.81 | 0.15 | 0.77 |

| Affective commitment | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.81 |

| Variables | Items | Mean | SD | Loading | AVE | ? | CR |

| KSA1 | 3.78 | 0.71 | 0.69 | ||||

| KSA HR practices (HR1) | KSA2 KSA3 KSA4 | 3.88 3.64 3.11 | 0.81 0.42 0.66 | 0.70 0.74 0.82 | 0.841 | 0.821 | 0.79 |

| KSA5 | 3.69 | 0.91 | 0.79 | ||||

| Total | - | 3.62 | 0.75 | - | |||

| MOT1 | 2.55 | 1.00 | 0.77 | ||||

| Motivation | MOT2 | 3.66 | 0.55 | 0.89 | |||

| HR practices | MOT3 | 3.90 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.721 | 0.792 | 0.81 |

| (HR2) | MOT4 | 2.97 | 0.59 | 0.75 | |||

| MOT4 | 3.67 | 0.45 | 0.80 | ||||

| Total | - | 3.35 | 0.68 | - | |||

| EMP1 | 3.50 | 0.78 | 0.74 | ||||

| Empowerment | EMP2 | 3.89 | 0.84 | 0.73 | |||

| HR practices | EMP3 | 3.58 | 0.49 | 0.84 | 0.810 | 0.782 | 0.76 |

| (HR3) | EMP4 | 3.46 | 0.76 | 0.86 | |||

| EMP5 | 3.73 | 0.59 | 0.73 | ||||

| Total | - | 3.63 | 0.77 | - | |||

| IR1 | 3.44 | 0.58 | 0.70 | ||||

| In-role performance (JP1) | IR2 IR3 IR4 | 3.74 3.65 3.48 | 0.68 0.69 0.77 | 0.75 0.81 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.881 | 0.78 |

| IR5 | 3.78 | 0.80 | 0.77 | ||||

| Total | - | 3.61 | 0.79 | - | |||

| IN1 | 3.55 | 0.74 | 0.69 | ||||

| Innovative performance (JP2) | IN2 IN3 IN4 | 3.87 2.77 3.68 | 0.75 0.66 0.81 | 0.73 0.80 0.72 | 0.711 | 0.821 | 0.76 |

| IN5 | 3.75 | 0.75 | 0.76 | ||||

| Total | - | 3.52 | 0.71 | - | |||

| AF1 | 2.40 | 0.71 | 0.74 | ||||

| AF2 | 3.69 | 0.46 | 0.68 | ||||

| Affective commitment (AC1) | AF3 AF4 | 3.71 3.70 | 0.58 0.76 | 0.84 0.86 | 0.798 | 0.801 | 0.88 |

| AF5 | 2.79 | 0.89 | 0.76 | ||||

| AF6 | 3.88 | 1.04 | 0.81 | ||||

| Total | - | 3.37 | 0.74 | - |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | - | |||||

| 2 | 0.55* | - | ||||

| 3 | 0.48* | 0.40* | - | |||

| 4 | 0.71* | 0.69* | 0.63* | - | ||

| 5 | 0.50* | 0.73* | 0.78* | 0.60** | - | |

| 6 | 0.39* | 0.57* | 0.68** | 0.66* | 0.59* | - |

| 1: KSAHR practices, 2: motivation HR practices, 3: empowerment HR practices, 4: in-role job performance, 5: | ||||||

| innovative job performance, 6: affective commitment. | ||||||

| *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level | ||||||

| ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level | ||||||

| Index | Value | Rule | Decision |

| CMIN/DF | 1.890 | value < 3 | Confirmed |

| GFI | 0.922 | value > 0.90 | Confirmed |

| AGFI | 0.931 | value > 0.90 | Confirmed |

| CFI | 0.910 | value > 0.90 | Confirmed |

| RMSEA | 0.050 | value < 0.08 | Confirmed |