1.

urban bop consumer and exploratory factor analysis(EFA).

2. I. Backdrop

n the world history of prolonged development discourse, poverty remained an economic, social, political and moral predicament. However, in 1980's Management experts and academicians entered the arena and provided probable solutions to the obstacles imposed by poverty. In the context, the two prominent management school of thoughts emerged to eradicate or least alleviate poverty was pioneered by M. Yunus (Bangladesh, 1980) and Late CK Prahalad and his coauthors (1999). M. Yunus (1980), suggested the concept of Microfinancing and C. K. Prahalad introduced 'base/bottom of the pyramid' (BOP) strategies, for poverty alleviation (Karnani, 2017). Both these market-oriented approaches promised win-win solutions, i.e., reduce poverty while simultaneously making profits. BOP also known as subsistence markets in the literature (Viswanathan, 2008; Elaydi and Harrison, 2010; Viswanathan et al., 2010;Weidner et al., 2010), refers to a situation when resources are just sufficient to meet the day-to-day living (Mulky, 2011). It represents an integral market as concerned with the living standards of more than 4 billion people living on less than $1,500 Per annum (PPP basis), i.e., world's lowest-income segment .

The BOP proposition coined by Prahalad (1999), asserted that private companies could earn significant profits by selling to poor, as there exists much-untapped purchasing power at the BOP. This approach had not-so easy acceptance because it questioned earlier traditional and economic tenets based on the western market. Further, BOP approach did not bring desirable results evident by failed first few attempts to enter BOP market segment. The failure was a result of faulty marketing strategy adopted by companies. Hitherto the marketing models application were mainly missing from poverty alleviation derives (Kotler, 2009). The emergence of BOP approach and subsequent failure of efforts made by MNCs entering this market imposed the biggest challenge in the history of marketing era (Kotler, 2009). In I other words, beliefs of thinking that BOP markets required the same set of methods and approaches as the developed market, proved wrong. Indeed companies raised issues such as, how can "Promotion" be relevant in "media dark" areas and how "Place" concept can be applied to an area with no formal market. Further, what can be the right "Price" to consumers with irregular income; and how can a fragile product work in a hostile environment. Previously, entrant firms started with westernized products and made it less costly to produce to satisfy subsistence consumers. There was a dire need to understand the consumer behavior in this market; thereby design an appropriate consumer-centric marketing-mix. However, the literature on subsistence marketplace is still evolving with research papers on BOP or subsistence market started integrally from 1997. Only few research papers were published until 2000, and maximum research papers were published during 2006-2011. It implied increased attention to the BOP concept by academicians since 2006 (Goyal et al., 2014). The research approaches were predominantly non-empirical, and out of the few empirical research studies, none of the research paper used quantitative model generalization. It indicates the predominance of conceptual studies and lack of focus on empirical studies. Since there is lack of quantitative data-oriented studies, seeking deliberation, current research focuses on quantitative analysis and building an integrated theoretical framework. This study tries to establish a consumer-centric marketing mix for BOP market and investigates the impact of marketing-mix on the subsistence consumer buying decision.

3. II. Review of Literature and Theoretical Framework

There is a lack of research on understanding consumer behavior in subsistence markets. Few researchers (Purvez, 2003;Banerjee and Duflo, 2006;D'Andrea et al., 2006;Viswanathan et al., 2008;Viswanathan et al., 2010) have begun to extend the discussion on subsistence marketplaces beyond the advocacy for increased engagement with this market. There is a need to expand previous research to understand the livelihoods of subsistence consumers. Earlier studies in BOP literature were confounded to Bangladesh (Purvez, 2003), Zimbabwe (Chikweche, 2008;Chikweche & Fletcher, 2012) and South India (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002;Viswanathan et al., 2010). India has always been a testing ground of BOP proposition. However, most BOP research studies were performed in Rural BOP segment of India. BOP literature provides marketing strategies adopted by firms without understanding the ground realities from the perspective of BOP consumers. Thus, literature is derived from other disciplines to establish a consumer-centric marketing mix.

4. III. Urban Bottom of Pyramid

There are several views on empirically defining the BOP segment (Sharma and Nasreen, 2017a). In an article by Chikweche & Fletcher (2012), explained that 'there will never be an agreement on actual size and distribution of the market, but it is an important market which requires increased research.' Various scholars have defined and classified the BOP market (Hart, 2002;Prahalad, 2004

5. IV. Food Market at World's Bop

According to WRI report (2007), significant categories on which BOP consumers spend their income are-food, energy, housing, transportation, health ICT and water (Annexure 2). Food sector represents the most significant market (about 58% of the BOP market) as the substantial part of their meager income is spend on food consumption. Food market formed an essential market for both rural and urban Indian BOP. According to IFMR (2011), rural household earnings are firstly used towards fulfillment of survival needs and secondly, investments required to assure health.

6. V. Marketing-Mix for Food Retailing

McCarthy (1964) summarised the marketing mix as a combination of all of the four factors, namely product, price, promotion, and place. The marketing mix paradigm has dominated marketing thought, research and practice (Grönroos, 1994), and "as a creator of differentiation" since it was introduced in the 1940s. Marketing scholars identify marketing-mix as a controllable parameter that firms use to influence the consumer-buying process (Brassington & Pettitt, 2005;Kotler, 2010). Since the current study involves food retailing, thus literature relates to marketing-mix in food and retailing. Each element of the marketing-mix is reviewed in the context of food purchase behavior to circumscribe the adequacy of the current state of the marketing-mix framework and the modifications required to accommodate BOP consumer's needs.

7. a) Product

In the context of current research, product offerings include food items purchased at subsistence marketplace. The BOP segment spends a substantial part of their meager income on food consumption (WRI, 2007). Even though the BOP segment pays more than 60% of the total income on food items, still they end up buying inferior quality goods at higher prices ( , found small packages were more affordable and thereby increased consumption and allowed consumers to quickly switch product with negligible switching cost (Jaiswal, 2007). Prahlad (2004) challenged the conventional assumption that BOP segment is not brand conscious and stated poor care about brands as to the brands are proofs of quality. Another study suggested poor are interested in quality, access to credits and lure of brand names (Moore, 2006). In a survey conducted by Viswanathan et

8. b) Price

Pricing of food is essential factors that shape individual choices (France, 2003). Price sensitivity is recurring determinant cited in BOP and low-income consumer literature (Chattopadhyay et al., 2005). Given the significance of cost-saving consumers assess and compare while purchasing food items (Nevin & Seren, 2010). According to the BOP literature, BOP consumers may not only consider the lower price while making a purchase. The results of the study carried out in South India by Viswanathan et al. (2010) indicated concerns such as fairness, product quality, and right price equally relevant influencers for these consumers. Chikweche et al. (2010) conducted qualitative research in Zimbabwe for studying the factors influencing purchase by subsistence consumer. They considered 'Value and appeal of the offer' were reflected in the ability of the offer to satisfy physiological needs.

9. c) Place

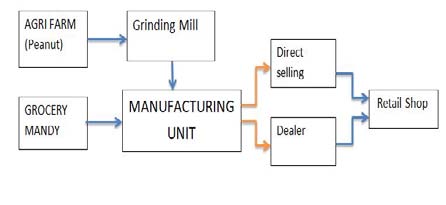

Physical accessibility to products is considered as a critical challenge for both consumers and firms in BOP markets (Austin, 1990;Johnson et al., 2007). The access to the product is hindered by weak supporting infrastructure and weak distribution infrastructure which made the traditional distribution channels both longer and more expensive (Nwanko, 2000;Fay and Morrison, 2006). Use of both formal and informal distribution channels was indicated in existing literature to enhance the interaction between consumers and firms. The informal distribution channel was linked to the social network in communities (Mahajan and Banga, 2004;Layton, 2007). Informal distribution channel emerged complemented by, or co-exist with, informal systems to serve a similar set of needs (Nkamnebe, 2006). These informal distribution systems were common in BOP market where there are weak infrastructure and lack of capital limits the development of formal marketing systems (Kaynak and Hudanah, 1987). Although informal distribution systems provide competition to the formal systems, at times the two supplement each other (Layton, 2007).

10. d) Promotion

BOP is a dark media area with lack of adequate communication infrastructure (Chickweche et al., 2012). Consumers are faced with the challenge of accessing Volume XVIII Issue III Version I Year ( ) information from firms. Since communication media is beyond the affordability of BOP consumer and there are frequent power electricity cuts in subsistence marketplace (Chickweche et al., 2012). In Research conducted in Zimbabwe BOP, it was found marketer preferred "Below the line media" over "Above the line media" (Chickweche et al., 2012). Given the mass illiteracy of target audience thus, in engaging BOP consumers, marketers relied on below the line media. Above the line media used by marketers included print, Radio, TV, Internet, outdoor and newspapers. However, in implementing the below the line medium, the critical conduit was a social network (Chickweche et al., 2012). Further, it was found aggressive marketing and Advertising via print outdoor, and television of international brands may lead the poor consumers to divert their scarce resources from consumption of Core bundles to non-core bundles (Jaiswal, 2008;Davidson, 2009;Gupta and Jaiswal, 2015;Karnani 2007Karnani , 2008Karnani , 2009)). Another study conducted in South India also fortified this finding and explained the social source of product information is more reliable than non-social sources -marketer related sources (advertising, a label on product packages) as well as media controlled sources (TV, newspaper, radio, and Internet). In the social source of information, groups and family or friends were preferred over neighbors and marketplace interaction. Another source of information included Government and community leaders (authority controlled) which was again less preferred.

11. VI. Research Context

The current research study defined subsistence marketplace as those households earning less than Rs. 8000 per month, clustered in the area with lack of civic infrastructure (Sharma and Nasreen, 2017). Thus, urban slums and shantytowns with a family earning fewer than Rs. 8000 was considered as the sampling frame. "The Challenge of Slums" (UN-HABITAT, 2003) reported that one billion people -approximately one-third of the world's urban inhabitants and a sixth of all humans live in slums. India alone constitutes about one-third of the global slum population. This research study was conducted in the high-density slums of Delhi (Capital of India). Delhi comprised of 675 identified Slum clusters in ten zones (Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), 2015). There is an absence of sampling frame because the Govt and NGO do not adequately map BOP market or subsistence marketplace or urban slums (Sharma and Nasreen, 2017b). Further, they do not hold legal title or deed to their assets (e.g., dwellings, farms, businesses) making it difficult to formalize these colonies (Hammond et al., 2007). In addition, heavy dependence on informal economy hinders in accurately determining their income.

To understand the food offering made at subsistence marketplace, report by National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) on Household Consumer Expenditure was analyzed. NSSO conducted 68th round survey on more than 250 food items for consumption. The item wise data on household food consumption collected in the NSS survey were grouped into nine broad food categories. Unfortunately, BOP segment thrives under the condition of limited income and restricted market choices. Therefore, for this research, the food items considered can prong into two broad categoriesa) Core Food Items It includes food items, which forms a staple diet for bottom fractile classes in India. Core items are imperative and easily accessible to this market or made easily accessible by governmental initiatives as considered being essential for living. In India consumption of rice, wheat and sugar are made available to below poverty line buyers at a subsidized rate through Fair Price Shops, known as Public Distribution System. Further Core items are generic and not much brand choices offered for these to BOP or subsistence market segment (Sharma and Nasreen,2017b). However, perishable food items are not considered as requires a different marketing mix, which cannot be generalized to this segment.

12. b) Non-core food items

This category includes the components infused by NSSO 68th round under the head of "beverages, refreshment, and packaged processed food."

This research study is limited to defining a marketing mix for "Core" food purchases by BOP segment in urban BOP market. Under Core food items purchase behavior of three items, i.e. 'Cereal' (rice (PDS/other sources), wheat (PDS/other sources), jawar, bajra, and maize.)', 'Sugar' and 'Pulses' are taken into consideration.

13. VII. Research Objectives

With differences in the circumstances faced by BOP consumers, consumers' decision-making not necessarily follows the process outlined in previously established models. Thus, the purpose of this study is "redefining the marketing mix at the BOP" (Sharma and Nasreen, 2017b). Thereby, this research study determines the nature of the impact of consumer-centric marketing-mix elements on the actual food purchase behavior of BOP consumer. The research objectives of this study can be summarised as follows-

To determine the socio-demographic profile of BOP consumers (gender, age, education, and income) in a slum area of Delhi (a) Core Food Items (b) Non-core Food Items

To understand the actual purchase behavior or consumption spending on core food items at BOP in a slum area of Delhi.

To redefine the marketing-mix elements for core food items at the bottom of the pyramid in slum areas of Delhi.

To determine the impact of marketing mix elements for core food item on consumption at the BOP in slum areas of Delhi.

14. VIII.

15. Development of Hypothesis and

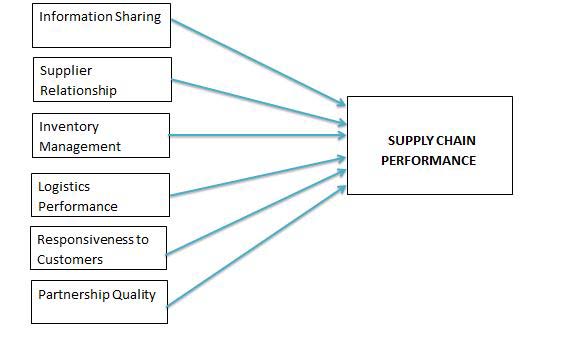

Research Framework Marketing-mix is recognized as an integral factor in determining purchase behavior. For the current research study, the foremost objective is to redefine the marketing-mix, therefore marketing mix is taken as an independent variable, whereby marketing-mix is assigned based on McCarthy (1964)'s Conceptualisation of 4Ps.

16. b) Product and Purchase Behaviour

Product quality shapes retailers' reputation and influences consumer-buying decision at stores (Pan& Zinkhan, 2006). Chaudhuri and Ligas (2009) suggested that product value is positively associated to purchase behavior and customer loyalty in the retail sector. Consumers assess multiple dimensions of food products to form their purchase decision. Hence the following hypothesis has been developed: H1: Product factor positively influences consumer-buying behavior of core food products in slum areas of Delhi.

17. c) Price and Purchase Behavior

Conventionally high retail price is reflected in immediate monetary cost and obstructs the consumer purchase behavior while a low price or competitive price leads to an increase in store traffic and product sales (Barbara et al., 1996;Pan & Zinkhan, 2006). Hence, the following hypothesis has been formulated: H2: Competitive price positively influences consumerbuying behavior for the essential food items in slum areas of Delhi.

18. d) Place and Purchase Behavior

Most researchers acknowledge that a convenient location advances store patronage (Jabir et al., 2010). Empirical evidence confirmed that convenience significantly affects consumer purchase of food products (Maruyama & Trung, 2007). Hence, the following has been hypothesized.

19. H3: Place aspect positively influence consumer buying behaviour for the essential food items in slum areas of Delhi e) Promotion and Purchase Behavior

Promotion is a marketing activity that brings traffic into stores and generates sales by communicating current offerings to targeted consumers (Dunne et al., 2010, p. 392). Dunne et al. (2010) proposed four basic types of promotion: advertising, sales promotions, publicity and personal selling. A study conducted in China (McNeil, 2006) revealed that consumers pay considerable attention to sales promotion (e.g., gifts, sampling, loyalty programs, discounts, and coupon) when selecting stores. Hansen (2005) demonstrated that promotional tools such as print advertisements, direct mail, customer loyalty and discount attract consumers to retail stores, leading to their purchase. Maruyama and Trung (2007) found that in-store advertising (e.g., panel, billboards, and flyers) had strong potential in affecting Vietnamese consumers' purchasing decision toward food products. Hence the following hypothesis has been developed:

20. H4: Promotion factor positively influence consumer buying behaviour for the core food items in slum areas of Delhi f) Theoretical framework

Based on the current research hypothesis following research framework is developed

21. Research Methodology

To redefine the marketing-mix in context of BOP segment for Essential food items a deductive and quantitative approach was employed (Saunders et al. Based on the extensive review of the literature, the operationalization of constructs can be provided in Annexure 3. The buying behavior was measured in terms of Monthly household Consumption spending; Frequency of purchase food items and Quantity purchased every time (Ali et al., 2010;Nguyen et al., 2015). Marketing-mix elements section was further divided into four parts-Product Mix, Price mix, Place Mix and Place-Mix. Each sub-section included items measured on the five-point Likert scale whereby, the five response categories, ranged from 'strongly disagree' to 'strongly agree' (Malhotra and Briks, 2006). Since the respondents were majorly illiterate, a Five-Points Likert scale was employed. Pre-test and pilot study are both essential parts of questionnaire survey design (Sekaran, 2003), to validate instrument and ensure it is free of errors. In this research study, the pre-test was conducted by distributing questionnaires to 10 eminent professors in related fields. The changes recommended were accommodated in the questionnaire. Integral insights provided were regarding definition of BOP consumers, Homogeneity in consumption habits of BOP consumers and fearful behavior of BOP community towards the surveys. In addition, 15 respondents were selected by judgmental sampling from the slum area of Uttam Nagar (Delhi). The respondents were asked to propose possible difficulties with the questionnaire design. It allowed translation of the survey instrument in local Language (Hindi).

A pilot study was administered in slum areas of Mangol Puri and Kathputli colony (Urban slums, Delhi) on the 100 Households with an excellent response rate of (about 83%). The sample composed of 44 females and 56 males with 64 respondents in the income bracket of Rs. 2001-4000. Out of the 100 households, 88 were covered under the Public Distribution Scheme (PDS). In the pilot study, a reliability of the items adopted in the questionnaire was evaluated using the internal consistency test of Cronbach's alpha. Cronbach's alpha estimate value above 0.70 is regarded as acceptable (Nunally, 1978). Each of the measures used in the pilot study displayed adequate reliability with Cronbach's alpha values of Product (0.951), Price (0.931) and Place (0.885) except Promotion (0.659). To ensure Cronbach's alpha for Promotion to be greater than 0.70 PRM5 (Neighbours) was dropped from final survey instrument. After dropping PRM5, the internal consistency increased to 0.729.

22. X. Data Collection

The six urban slum areas with the highest density of population (per slum area) were selected and from every slum cluster, 100 households were interrogated. These six slum clusters included Mangol Puri, Kathaputali Colony, Zakhira, Nangloi, Peeragahri and Tigri from where a survey of 600 families was conducted. Local leaders informed all the slum dwellers about the study, and people were asked to visit "Aanganwadi," "Ranbasera" and another place of gathering (Self-selection sampling). The researcher then based own judgment to select cases which best meet research objectives. The sample contained 286(47.7%) female and 314 (52.3%) male respondents. In the age group of 25-44 years about 83 % of the respondents were covered and on extreme ends, i.e., below 24 years, and above 55 years, only 5.2% and 4% respondents were included (Table 1).

Volume XVIII Issue III Version I Year ( )

23. Analysis and Results

Data collected were analysed through a series of validated tools and procedures. The factor analysis was carried followed by testing the validity (Construct and Discriminant) using SPSS v 21. The results and findings of the study can be represented in the following sub-sections.

24. a) EFA for Redefined Marketing-Mix of Core Food Items

Before conducting EFA analysis data screening was performed, whereby three main issues-Missing values, Outliers and unengaged responses, were addressed. Since data was administered by personally interviewing the respondents, no missing values were noticed. After that, outliers were determined for the consumption spending. To identify the multivariate outliers, Cook's D method was applied, and top 5 % of the outliers with Cook's distance more than 0.01 were eliminated. The number of multivariate outliers observed was 29(4.83%) out of the total 600 cases. Thus, the number of respondents after the final study was 571. Thereby, EFA using Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation was performed to see if the observed variables loaded together as expected and meet criteria of reliability and validity. The pattern matrix extracted variables grouped into four factors. The items with low communalities, low factor loading, and substantial cross loading, were deleted to retain items divided into four highly correlated constructs. A factor structure depicting convergent and discriminant validity were obtained (Annexure 4). After performing the EFA, the marketing-mix elements were renamed or redefined (Table 2). The first factor consisted of eight variables and named as 'Place Loyalty,' the second factor consists of five variables and is named as 'Reasonably essentials.' The third factor consists of four variables, which are named as 'Price sensitivity.' The fourth factor represents the 'Social sources' to reach BOP consumers.

25. b) Hypothesis Testing

The correlation coefficients established significant positive associations between the redefined marketing-mix (predictors) and Consumption spending (dependent variable). Then multiple regression was conducted to determine the relative impact of marketing-mix elements on buying behavior. However, before regression, diagnostics were performed to ensure generalizability of the model (Fields, 2013).

26. c) Assessing the Regression Model: Diagnostics

Firstly, multicollinearity was evaluated implying the absence of a perfect linear relationship between two or more of the predictors. It was performed using variance inflation factor (VIF). The largest VIF was less than 10 thus there was no cause for concern (Myers, 1990). Further, the average VIF was almost equal to 1 hence the regression model was not biased.

To test the normality of residuals, histogram and normal probability plot of ZRESID against Z PRED were analyzed. The histogram depicted the shape of the distribution of monthly consumption spending which is roughly normal (Annexure 5).

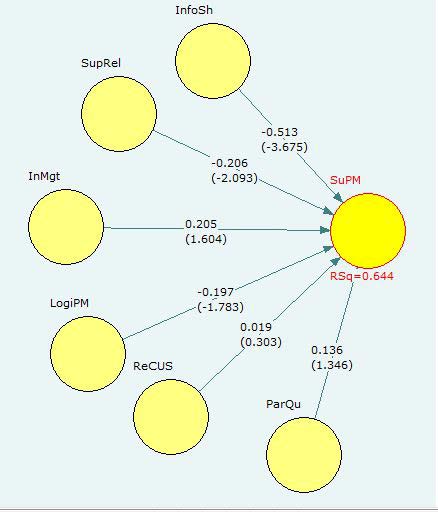

27. d) Regression Model

From Table 3, R has a value of .800, and because there is only one predictor, this value represents the simple correlation between marketingmix factors and Consumption spending. The value of R square is .640. Thus, marketing-mix factors can account for 64% of the variation in Consumption spending for the core food items. It suggested that 36% of the variation in record consumption spending cannot be explained by marketing-mix. The adjusted R2 is very close to the observed value of R2 (.640) indicating that the crossvalidity of this model is good. The model causes R2 to change from 0 to .640, and this change in the amount of variance explained gives rise to an F-ratio of 252.381, which is significant with a probability less than .001.

28. XII. Key Findings

The sample drawn comprised of 600 respondents, coming from six different regions of Delhi. Responses from 286(47.7%) of female and 314 (52.3%) male respondents were obtained, selected in equal number (100) across different slum areas. Within the age group of 25-44 years about 83 % of the respondents were covered and on extreme ends, i.e., below 24 years and above 55 years, only 5.2% and 4% respondents are included.

The average consumption spending of the sampled BOP consumers for Core food categories was Rs. 2576.7745. However, the number of times they make purchase varied substantially with six times (Approx.) and 26(approx.) for the core food. The maximum consumers spent Rs 2800 for the core food were observed. The range of consumption spending for core-food category was Rs. 550-Rs 4250 with the standard deviation in consumption spending was Rs 779. However, the maximum number of visits consumers make for purchase varied from nine visits for core food categories.

The redefined marketing-mix for core food items constituted four constructs. The first factor comprised of eight elements and was named as Place Loyalty, the second factor of five variables and described as "Reasonable / essentials." The third factor consisted of four variables, named as "Price sensitivity." The fourth factor represents the "Social sources" to reach BOP consumers.

The factors demonstrated sufficient convergent validity, as their loadings recorded to be above the recommended minimum threshold of 0.350 for a samples size of 300 (Hair et al., 2010). The factors also demonstrate sufficient discriminant validity, as the correlation matrix shows no correlations above 0.700, and there are no problematic cross-loadings. The way to test reliability in an EFA is to compute Cronbach's alpha for each factor. Cronbach's alpha for all the factor was reported to be above 0.7 although, ceteris paribus, the value will increase for factors with more variables, and decrease for factors with fewer variables.

The bivariate correlations were computed to analyze the proposed relations between variables. The Pearson's correlation coefficients confirmed significant positive associations between the redefined marketingmix and Consumption spending (Table 5). The final model derived from data collection is illustrated in Figure 4.

29. XIII. Discussions and Marketing Implications

The current study found that in context of the core food items the product-mix comprised of five elements Freshness of food items, Availability in Small quantity/ Sachets, Accurate measurement of quantity, Packaging and Food label/ Safety Mark. These items suggested that BOP consumers were not much sensitive towards variety and brand; instead, they wanted the basics or core layer of product to reasonably meet their wants. Thus, Product-mix was named as reasonable or essentials. The core food items were purchased in small quantity, which corroborated with the findings of Prahalad & Hammond (2002); and . The assertion that the BOP consumers are concerned about brands (Prahalad, 2004) was violated in case of the core food items.

Existing studies suggested BOP consumers were price sensitive and their primary concern was to satisfy the physiological need in a best possible way (Chattopadhyay & Laborie, 2005). In case of core-food items BOP consumers exhibited a high level of price sensitivity and price mix comprised of four items, i.e., Price charged less than List price, Price per unit charged when bought product in small quantity, Discount offered and Availability of product on credit. Thus, the price-mix for core food items is named as Price sensitivity index. This finding corroborated with the existing research done in the field of BOP. The lowincome consumers considered price as a dominant factor while making a purchase. (Viswanathan et al., 2008) In the Current study, Place aspect manifested to be the most critical factor leading to the purchase of the core food items. The place-mix for core food be item redefined to include-Nearness of the shop/Less Travelling, Credit Facility, Courteous Treatment, Standard price and quality, Product Knowledge of shopkeeper, Trust/ Familiar local Shopkeeper, Wider Choice and Not much consideration to easy Return Policy of the shopkeeper. However, the significant gap not highlighted in the previous BOP researches was the presence of fair market shops or ration shops for procuring core food items. It resulted in less negotiating power in the hands of BOP consumers. As a result, the redefined place-mix for core food items is named as Place loyalty aspects.

In the research conducted in Zimbabwe BOP, it was found marketer preferred "Below the line media" over "above the line media." Above the line media used by marketers included print, Radio, TV Internet, outdoor and newspapers. For the core food item, significant sources of information included Family/friends, Groups, the absence of Internet usage and No Government sources. It indicated reliance on social sources of information, so this media-mix was named as social media-mix.

30. XIV. Conclusion and Future Gaps

The current study offered several research insights, which had implications for the academicians, policymakers, and practitioners working at BOP market. The current research work filled various gaps found in the existing literature. This study focused on modifying and determining marketing mix elements for core and noncore food items at the BOP in slum areas of Delhi. This study was propelled by the research questions of inculcating the BOP or subsistence marketplace into the mainstream market and thereby efficiently serving it. The challenge was how to help the poor who does not have much consumption power and money. Thus, the current research made an effort to fill previous research gaps and employed empirical research to develop an inclusive marketing-mix for core food items (Goyal et al., 2014).

Due to, cost and geographical constraints, the researcher used a non-probability sampling. This technique calls into question the representativeness of the sample. The researcher recommends for the future studies to rely on a probability sampling to get more representative results. A probability sampling method means that every person has equal chances of selection in the sample. The results obtained with this method can be generalized to the whole target population within a specified margin of error.

Sample size would lead to broaden the findings to the targeted population and increase the reliability of the whole study.

The questionnaire framework was challenging to create it is suggested that the questions asked to BOP segment should not be too long and time-consuming. The BOP consumers are an unknown target for marketers this is why more questions (both complex and personal) might have conducted to more precise results and emphasize some trends. Further, it is recommended to use 3 to 5 point Likert scale, thereby, translated in the local language to enhance understandability. Although the research study is not-contrived results were observed to get improved when discussion on the other related aspects was encouraged

The researcher was aware that when it comes to studying BOP markets, prejudices and biases can arise in researchers understanding because they are not familiar with BOP way of life. To make sure such mistakes do not happen, the researcher relied on knowledgeable intermediaries to pretest the questionnaire and asked their help to understand elusive answers from respondents. In spite of these precautions, the researcher experienced some problems such as the religion of some respondents that deter them from answering all the questions. Future researches should forecast such constraints and adopt its questionnaire.

The macro-environmental constraints such as inflation, the role of Govt., other environmental factors, are prevalent in India. These constraints could potentially influence purchase decision by BOP consumers. Future studies are expected to be on the path of macroeconomic factors.

Another investigation opportunity lies in advancing the research on the peculiarities of the impact of below and above the line direct marketing activities on consumer purchase.

Culture is an integral aspect of buying-decision in India, where there are varied religions and culture. Thus, it

31. Year ( )

becomes imperative to integrate its influence on the application of consumer behavior theory across the various market. It forms a gap for future research studies.

32. Annexures

| Demographics | Categories | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Gender | Male Female | 314 286 | 52.3 47.7 | |

| Mangol Puri | 100 | 16.7 | ||

| Kathaputali Colony | 100 | 16.7 | ||

| Slum Area | Zakhira Nangloi | 100 100 | 16.7 16.7 | |

| Peeragahri | 100 | 16.7 | ||

| Tigri | 100 | 16.7 | ||

| Below 24 | 31 | 5.2 | ||

| Year 2018 | Age (Transformed to Categorical variable) | 45-54 55 And Above No Schooling 25-34 35-44 | 47 24 6 255 243 | 4.0 1.0 7.8 42.5 40.5 |

| Below 4 Years | 159 | 26.5 | ||

| Volume XVIII Issue III Version I | Year of Schooling Household Income Marital Status Family members | Below 8 Years Below 12 Years 12 Years And Above Below Rs. 2000 Rs. 2001-Rs.4000 Rs. 4001-Rs6000 Rs.6001-Rs8000 Married Unmarried 0-2 3-5 | 218 217 0 6 156 208 230 588 12 72 411 | 36.3 36.2 0 1.0 26.0 34.7 38.3 98.0 2.0 12.0 68.5 |

| ( ) E | 5 above No Ration Card | 117 221 | 19.5 36.8 | |

| Ration card | Yellow Ration Card | 229 | 38.2 | |

| Red Ration Card | 150 | 25.0 | ||

| © 2018 Global Journals 1 |

| Variable | No. of items | Cronbach's Alpha |

| Place Loyal | 8 | 0.970 |

| Core product | 5 | 0.941 |

| Price Sensitive | 4 | 0.917 |

| Social sources | 4 | 0.779 |

| R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | R Square Change | Change Statistics F Change df1 df2 | Sig. F Change | ||

| .800 | .640 | .638 | 468.79882 | .640 | 252.381 | 4 | 567 | .000 |

| Table 4 provided b-values, which indicate the | Social centric Sources (b = 56.621) indicates that as | |||||||

| individual contribution of each predictor to the model. | predictor increases by one unit Consumption Spending | |||||||

| The b value for Place Loyalty (b=483.973), Basic | increases by equivalent b times the increment. | |||||||

| Product (b=336.496), Price Sensitivity (b=194.655), and | ||||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients B Std. Error | Standardized Coefficients Beta | T | Sig. | |

| (Constant) | 2576.774 | 19.601 | 131.458 | .000 | |

| Place Loyalty | 483.973 | 19.619 | .621 | 24.669 | .000 |

| Basic Product | 336.496 | 19.619 | .432 | 17.152 | .000 |

| Price Sensitivity | 194.655 | 19.619 | .250 | 9.922 | .000 |

| Social Sources | 56.621 | 19.619 | .073 | 2.886 | .004 |

| Thus based on the findings, regression equation can be given as follows- | |||||

| Regression Equation | |||||

| Consumption Spending i = b 0 +b 1 Place Loyalty + b 2 Basic Product + b 3 Price Sensitivity + b 4 Social Sources | |||||

| Consumption Spending i = 2576.774+ 483.973 Place Loyalty+ 336.496 Basic Product +194.655 Price | |||||

| Sensitivity+56.621 Social Sources | |||||

| Core Food Items | ||||

| RH | Hypothesis | Test Statistics (Standardised coefficient) | Results (p=0.05) | |

| 1 | PLC | CSPEND | 0.621(p=0.00) | Reject |

| 2 | PRD | CSPEND | .432 (p=0.000) | Reject |

| 3 | PRC | CSPEND | 0.250(p=0.000) | Reject |

| 4 | PRM | CSPEND | 0.073(p=0.004) | Reject |

| Codes | Place Loyal | Core product | Price Sensitive | Social sources | Items | ||

| PLC1 | .862 | Nearness of the shop/Less Travelling | |||||

| PLC2 | .932 | Credit Facility | |||||

| Year PLC3 PLC4 | Author .935 .749 | Definition of BOP | Market size and Courteous Treatment Potential Standard price and quality | Author adapted Banerjee and Duflo | |||

| PLC5 | .930 | Product Knowledge of shopkeeper | (2006) | ||||

| Year Year Global Journal of Management and Business Research Global Journal of Management and Business Research Volume XVIII Issue III Version I Volume XVIII Issue III Version I ( ) ( ) | 2001 PLC6 The World Bank (World Development Report (WDR,1990) WDR (2005) .810 PLC7 .858 Marketing Mix PLC8N .914 PRD4 .704 Consumption less than $1 per day Trust/ Familiar local Shopkeeper Four billion of which 1.1 billion people were living on less than $1 a day Wider Choice per person (PPP 1990) considered as extreme poverty Annexure 3: Operationalization of Variables Construct Operationalization Authors Rangan, Quelch et al (2007) expanded to $2 per person per day Karnani, 2007; Karnani, 2007(1) used 1.25$ per person per day(2005 No Easy Return Policy of the shopkeeper Freshness of food items Independent Variables (IV) WDR) 2002 Prahalad & Hart, 2002 BOP segment as consumers earning less than $1500 per annual per capita income (i.e. almost $2 per day PPP, 1990). Other characters of BOP-I. Product PRD5 .733 Availability in Small quantity/ Sachets 4 billion people at BOP with a market potential lies in the vast size of this market and represent multitrillion-dollar market. Prahalad & Hammond, 2002) 2004 Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004) People earning on less than $2000 or $2 per day, PPP rates Market potential of $13 trillion. Explained poverty penalty at BOP market India(Dharavi slum) 2007 Hammond, Kramer, Katz, Tran, and Walker's deed to their assets (e.g., dwellings, farms, businesses). Little or no formal education Hard to reach via conventional distribution, credit, and communications. estimated to $5 trillion. (Subramanian & Gomez-Arias, 2008) 2010 Viswanathan et al. Household in south India earning less than Rs 8000 per month. Other Characters are-Limited or no access to sanitation, potable water, and health care Lack of control over many aspects life (Viswanathan et al., 2007) one-to-one interaction marketplace strong social relationships interdependency among members majority of their income on daily necessities such as food Live in substandard housing (Prahalad, 2005) Have limited or no education Gupta & Jaiswal 2015(Gujrat) Fletcher 2010 PLC2 ii). Credit Facility PLC3 iii).Courteous Treatment PLC4 iv).Standard price and quality PLC5 v) Product Knowledge of shopkeeper PLC6 vi). Trust/ Familiar local Shopkeeper PLC7 vii). Wider Choice PLC8 viii). Easy Return Policy of the shopkeeper PLC9 ix).Bargaining opportunities IV. Promotion PRM1 i). Packaging Viswanathan et al. 2010, Chikweche & Fletcher 2010 PRM2 ii). Shopkeeper PRM3 iii). Family/friends PRM4 iv). Groups PRM5 v). Neighbours PRM6 vi). Market interaction PRM7 vii). Bulletin boards PRM8 viii). Newspaper PRM9 ix). TV PRM10 x). Radio PRM11 xi). Internet PRM14N .704 No Government Classification People are whose annual incomes are between $0-3 000 per capita per year (2002 PPP). Other Characters-Dependence on informal economy Lives in rural villages, or urban slums and shantytowns, Usually do not hold legal title or BOP makes up 72% of the 5,575 million people recorded by PRD1 PRD7 .892 Accurate measurement of quantity PRD8 .929 Packaging PRD9 .919 Food label/ Safety Mark PRC2 .860 Price charged less than List price PRC3 .934 Price per unit charged when bought product in small quantity PRC4 .909 Discount offered PRC5 .817 Availability of product on credit PRM3 .766 Family/friends available national household surveys and total purchasing power PRM4 .858 Groups PRM11N .763 No Internet | ||||||

| PRM12 | xii). Community Leaders | ||||||

| PRM13 | xiii). NGOs | ||||||

| PRM14 | xiv). Government | ||||||

| Dependent Variables (DV) | |||||||

| Buying behaviour | |||||||

| CONS1 | Monthly household Consumption spending | ||||||