1. Introduction

he literature on the performance of Islamic banks is still in its initial stages. Recent empirical efforts have begun to change this, but the findings in the literature are mixed and inconclusive. The analysis in this study addresses the gap in the literature on the comparative performance of Islamic and conventional banks. This paper mainly addresses the effects of bank size and location on the efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks operating in OIC countries by using two samples, a sample including all conventional and Islamic banks in OIC countries and a sample constrained to the countries in which both banking types operate. Some studies only concentrate on countries with both banking types, and other studies use a mixed sample. By using two samples, the outcomes of this study can give a better view of the performance of both banking types.

2. II.

3. Literature Review

According to Bader et al. (2007), efficiency has been examined in a number of different contexts: (a) cross-country comparisons or country-specific conditions, (b) foreign-owned banks versus domesticowned banks, (c) comparisons of bank type (e.g. large or small, specialized or diversified, retail or wholesale), (d) government ownership versus private ownership, (e) new versus old bank, (f) before and after mergers or acquisitions, (g) before and after a financial crisis (e.g., the 1997 Asian crisis), and (h) analyses of the effects of deregulation and liberalization. This paper analyzes and compares the efficiency (cost, profit and revenue) of conventional and Islamic banks. Also, the analysis is conducted based on size and location of both bank types. Bader et al. (2007) examines the cost, revenue, and profit efficiency of 43 Islamic banks and 37 conventional banks in 21 OIC countries from 1990 to 2005. Attention is given to bank size, age, and location. The profitability ratios are ROAA and ROAE. The revenue-efficiency category also consists of two ratios: NIM and other operating income to average assets divided by average assets. Finally, cost efficiency is represented by cost-income ratio (overhead divided by pre-provision income) and non-interest expenses ratio (the ratio of non-interest expenses or overhead plus provisions to the average value of assets). The results show no significant differences between Islamic and conventional banking systems on these indicators. The same results are obtained when the banks are grouped into small and large size based on their total assets. This indicates that the size of the banks in Bader et al. (2007) does not affect their cost, profit, or revenue efficiencies. Furthermore, the authors group banks based on their age. The results reveal no significant differences between the cost efficiencies of old and new conventional and Islamic banks. However, the NIM ratio for new conventional banks is significantly higher than the NIM ratio for new Islamic banks. There are no significant differences between old conventional banks and old Islamic banks in terms of revenue and profit efficiency. Finally, the study concludes that location does not impact the efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks.

Hassan, Mohamad and Bader (2009) explore the effects of size and age on the cost, revenue, and profit efficiencies of a sample of 40 banks (18 conventional and 22 Islamic) in 11 countries from 1990 to 2005. Those countries are OIC members located in the MENA region. The study uses a Data Envelope Analysis (DEA) non-parametric approach. The results suggest that there are no significant differences in the cost, revenue, or profit efficiencies of both bank types. Furthermore, the results reveal that large versus small banks, large conventional versus large Islamic, and small conventional versus small Islamic banks are no different in terms of efficiency. The study also indicates that large conventional banks and large Islamic banks are more revenue efficient than their small counterparts but small Islamic banks are more profit efficient. Nevertheless, these results are not significant. Moreover, there are no significant differences in efficiency between old conventional and old Islamic banks. The cost and profit efficiencies of old conventional banks are slightly better than they are for old Islamic banks. Old Islamic banks are more revenue efficient than old conventional banks though. The profit Abdul-Majid, Saal and Battisti (2010) compare the efficiency of Islamic and conventional banks using a sample of 23 Islamic and 88 conventional banks from 10 countries from 1996 to 2002. The authors use an output distance function, and the results indicate that the potential efficiency outputs of Islamic banks are lower than the potential outputs for conventional banks. The authors argue that constrained opportunities in terms of investments are the cause for the lower efficiencies in Islamic banks. Similarly, Abdul-Majid (2010) examines the efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks in 10 countries that have both banking types from 1996 to 2002. The sample consists of 23 Islamic and 88 conventional banks, and cost and output distance functions are used for the estimates. The results show that Islamic banks have higher input requirements than do conventional banks. Ariss (2010) analyzes the competitive conditions prevailing in Islamic and conventional global banking markets and investigates the differences in profitability between conventional and Islamic banks using a sample of 58 Islamic and 192 conventional banks across 13 countries from 2000 to 2006. Ariss uses a multi-variate analysis method and does not find differences in profitability levels across Islamic and conventional banks. In a smaller sample of banks with similar macroeconomic conditions, Srairi (2010) investigates the profit and cost efficiencies of 48 conventional and 23 Islamic banks from 1999 to 2007 in GCC countries. A stochastic frontier analysis is used, and the results indicate that conventional banks are better than Islamic banks in terms of profit and cost efficiency.

Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Merrouche (2010) compare conventional and Islamic banks, controlling for other bank and country characteristics. They use two samples-large and small-for the 1995-2007 period. The large sample includes 2,857 conventional banks and 99 Islamic banks across 141 countries. The smaller sample includes 397 conventional banks and 89 Islamic banks across 20 countries. The authors use z scores and a linear fixed-effects model to assess the difference between the two banking systems. The variables in their study are grouped into four categories: business model, efficiency, assets quality, and stability. The business model consists of three variables: fee income to total operating income, non-deposit funding to total funding, and gross loans to total loans. The efficiency category has two variables: overhead to total assets and cost to income ratio. The asset-quality effect is captured by the ratios of loan-loss reserves to total gross loans, loanloss provision to total gross loans, and non-performing loans to total gross loans. Finally, stability is measured by z scores, returns on assets, an equity-to-asset ratio, and maturity matching.

Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Merrouche (2010) show few significant differences in business orientation, efficiency, asset quality, and stability. Islamic banks are more cost efficient than conventional banks in the large sample, but not more profitable. The results for the smaller sample indicate that there is no difference in profitability between conventional and Islamic banks. However, the conventional banks are more cost effective compared to Islamic banks. Conventional banks that operate in countries with a higher market share of Islamic banks are less stable but more cost efficient. The study compares the effect of the recent financial crisis on both of the banking systems. The authors conclude that Islamic banks performed better than conventional banks during the financial crisis. The authors attribute this to the higher capitalization and liquidity reserves of Islamic banks.

In another cross-country study, Kaouther, Viviani and Belkacem (2011) examine the differences between conventional and Islamic banks with a particular focus on leverage and profitability. Using a sample of 109 banks (50 Islamic and 59 conventional) from 18 countries from 2004 to 2008 from the Thomson ONE database, they conduct t tests, binary logistic regressions, and a discriminant analysis using leverage and profitability ratios and their determinants. The findings show that ROA and ROE ratios are slightly higher (although not significant) for Islamic banks. However, the net-margin ratio shows that Islamic banks are less profitable than conventional banks, and the results are significant at the 5% level.

Olson and Zoubi (2011) compare accountingbased and economic-based measures of efficiency and profitability of 83 banks from 10 MENA countries from 2000 to 2008. The analysis, with country dummy variables, shows that GCC conventional banks are more cost efficient than non-GCC conventional banks and GCC Islamic banks. Also, the results reveal that Islamic banks in the GCC region are more profitable (ROE) than GCC and non-GCC conventional banks but are less cost efficient. Based on the overall results of their study, Olson and Zoubi argue that accounting-based and economics-based approaches give similar measures of relative bank performance but explain that they do measure different aspects of financial performance.

In an earlier study, Olson and Zoubi (2008) use 26 financial ratios to examine whether it is possible to distinguish between conventional and Islamic banks in GCC countries on the basis of financial characteristics alone. The financial ratios fall into five general categories: profitability, efficiency, asset quality, liquidity, and risk. The data period spans from 2000 to 2005. However, the number of banks differ from one year to another, with 25 banks (13 conventional and 12 Islamic) in 2000, 28 banks (14 conventional and 14 Islamic) in 2001, 47 banks (29 conventional and 18 Islamic) in both 2002 and 2003, 46 banks (28 conventional and 18 into logit, neural-network, and k-means nearest neighbor classification models to distinguish between conventional and Islamic banks. The results reveal that Islamic banks are more profitable than conventional banks. The findings for interest or commission income divided by average total assets show that the efficiency ratios are significantly smaller for Islamic banks and that net non-interest margins are significantly smaller for conventional banks. Also, asset-quality ratios vary between the two banking systems. The provision for loan losses to average total loans and advances, allowances for loan losses at the end of the year over average total loans, and advances used as asset-quality ratios are all smaller for Islamic banks. In contrast, the liquidity ratios are not significantly different between conventional and Islamic banks. However, the risk ratios indicate a significant difference between the two banking systems. The loans-to-deposits ratio is larger for Islamic banks, and the reverse is true for the ratio of liabilities to shareholder capital. The results from the risk indicators are consistent with the notion that Islamic banks are riskier than conventional banks. Metwally (1997) compares the performance of 15 conventional banks and 15 Islamic banks from all over the world in terms of liquidity, leverage, credit risk, profit, and efficiency by using logit, probit, and discriminate analyses. The findings suggest that, compared to conventional banks, Islamic banks rely on their equity to finance their activities and face more difficulties in attracting deposits. Second, Metwally finds that Islamic banks are more conservative in their lending and therefore have higher cash-deposit ratios than conventional banks. Finally, the study shows that profitability and efficiency are not different between conventional and Islamic banks.

In another cross-country study, Johnes, Izzeldin and Pappas (2009) use a financial-ratio analysis and a DEA to investigate the efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks in the GCC region from 2004 to 2007. For the financial-ratio analysis, the authors adopt the same ratios as Bader et al. (2007). The results reveal that Islamic banks are more revenue and profit efficient but less cost efficient than conventional banks. Specifically, ROAA is always higher for Islamic banks throughout the entire study period. However, the ratios of cost to income and non-interest expenses to average assets are higher for Islamic banks compared to conventional banks. The revenue-efficiency variables of NIM and other-operating income to average assets are higher for Islamic banks, but the results are only significant for other operating income. The findings of the econometric method indicate that gross efficiency is higher for conventional banks. In general, the findings show that the financial-ratio analysis and the econometric methods are complements rather than substitutes.

Iqbal (2001) compare the performance of conventional and Islamic banks operating in a dual-bank system. The sample consists of 12 banks for each bank type from seven countries from 1990 to 1998. The study uses t tests to compare several financial ratios grouped into five categories: asset quality, liquidity, deployment ratio, cost-to-income ratio, and profitability. The results indicate that Islamic banks are more cost and profit efficient. Akhter et al. (2011) use financial ratios to compare the performance and efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks in Pakistan. The study uses nine financial ratios in the areas of profitability (ROA, ROE, and total cost to total income), liquidity risk (net loans to asset ratio, liquid asset to customer deposits and shortterm funds, and net loans to total deposits and borrowing), and credit risk (equity to total assets, equity to total loans, and impaired loans to gross loans) from 2006 to 2010. The study shows no significant differences between conventional and Islamic banks in terms of profitability. However, there are differences in liquidity and credit performance, both in favor of Islamic banks. In another recent study on Pakistani banks, Hanif et al. (2012) compares the performance of 22 conventional banks and 5 Islamic banks from 2005 to 2009. They also use nine ratios grouped into four categories: profitability (ROA, ROE, and total cost to income), liquidity (net loans to asset ratio, liquid assets to customer deposits and short-term funds, and net loans to total deposits and borrowing), risk management (equity to total assets, equity to total loans, and impaired loans to gross loans), and solvency (Bank-o-meter model). Their findings suggest that conventional banks are more profitable (ROA and ROE) and liquid than Islamic banks. In contrast, Islamic banks are better in terms of credit risk management and solvency maintenance.

Samad and Hassan (1999) use financial ratios to compare the profitability performance of one Islamic bank, Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad, with eight conventional banks in the same country from 1984 to 1997. These ratios are grouped into four categories: profitability (ROA, ROE, and profit over total expenses), liquidity (cash-deposit ratio, loan-deposit ratio, current assets to current liabilities, and current assets to total assets), risk and solvency (dept-equity ratio, debt-to total-asset ratio, equity multiplier, and loan-to-deposit ratio), and commitment to the domestic and Muslim community (long-term loans to total loans, deposit invested in government bonds over total deposits, and mudaraba-musharaka to total loans). The study finds no significant differences in profitability between Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad and the conventional banks. Also, risk and insolvency ratios and commitment to the domestic and Muslim community ratios did not show any significant differences. Muslim community ratios include long-term loans to total loans, deposits invested in government bonds over total deposits, and mudarabamusharaka to total loans. However, the study indicates that Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad is more liquid than conventional banks. Safiullah (2010) replicates Samad and Hassan (1999) with some modifications to examine the Bangladeshi banking system. He uses a financialratio analysis to compare the ratios of profitability, liquidity, and solvency; business development, efficiency, and productivity; and commitment to economy and community of conventional and Islamic banks from 2004 to 2008. This study documents the superiority of Islamic banks in the areas of business development, profitability, liquidity, and solvency. Also, Samad (2004) uses a financial-ratio analysis to examine the comparative performance of Islamic and conventional commercial banks in Bahrain during the post-Gulf War period with respect to profitability, liquidity risk, and credit risk. The author uses nine financial ratios over the period from 1999 to 2001 for 15 conventional banks and six Islamic banks to compare the performance of both banking systems. The paper concluded that there is a significant difference in credit performance (equity-to-asset ratio, equity-to-net-loan ratio, and non-performing loans to gross loans), as the performance of Islamic banks is superior to that of conventional banks. Samad (2004) argues that this was probably largely due to the higher rates of equity per capita that the Islamic banks maintain in his study. The indicators of profitability (ROA, ROE, and cost-to-income ratio) and liquidity (net loans over total assets, liquid assets over customer deposits, and short-term funds and net loans over total deposits and borrowings) show no significant differences.

In a more recent study, this one on the Malaysia banking system, Masruki et al. (2011) compare the performance of two Islamic Banks (Bank Islam and Bank Muamalat) against benchmarks of conventional banks from 2004 to 2008. The authors use four financial ratios: profitability, liquidity, risk, solvency, and efficiency (NIM and net financing revenue over assets). The analysis utilizes equality-of-means tests. The findings reveal that Islamic banks are less profitable (ROAA and ROAE) than conventional banks but more liquid. Also, Islamic banks are more efficient than conventional banks. Furthermore, Abdul-Majid, Nor and Said (2003) examine the productive efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks in the country from 1993 to 2000 using a stochastic frontier cost function approach. They conclude that efficiency levels of conventional and Islamic banks are not different. Moreover, their results suggest that bank efficiency is not a function of ownership status (e.g., public or private, foreign or local). In addition, Mokhtar Also, the study reveals that full-fledged Islamic banks are more efficient than Islamic windows, whereas foreign Islamic windows are more efficient than conventional banks. Borkbh (2011) examines a sample of 17 Islamic banks and 15 conventional banks from 2000 to 2008 from eight Middle Eastern countries with dual-bank systems. The author uses a stochastic frontier approach to investigate both banking systems. The findings show that conventional banks are more technical, altercative, and cost efficient than Islamic banks.

Scholars have also compared the efficiency and performance of conventional and Islamic banks before, during, and after the recent financial crisis (2007)(2008). Bourkhis and Nabi ( 2011) attempt to answer two questions: "Have Islamic banks been more resistant than their counterparts to the 2007-2008 financial crisis?" and "Could the presence of Islamic banks in a conventional banking system enhance the overall systemic stability?" The authors collect data from 343 conventional banks and 64 Islamic banks in 19 OIC countries from 1993 to 2009 to analyze the financialcrisis effect on both banking systems' soundness indicators, including (capital adequacy, earnings and profitability, asset quality, efficiency and liquidity). The analysis uses equality-of-means tests and z scores. The equality-of-means results show that Islamic banks are more profitable than conventional banks before the crisis. During the crisis, large Islamic banks remain more profitable than the large conventional banks. However, Islamic banks become less profitable after the crisis. Also, their results show that large Islamic banks are more resilient to the financial crisis than small Islamic banks. The second approach shows that conventional banks are financially stronger than Islamic banks through the three periods (before, during, and after the crisis). Furthermore, small Islamic banks are financially stronger than large Islamic banks in the period before the financial crisis, and the reverse is true during and after the crisis. Also, the study reveals surprising results that contradict the notion that Islamic banks are more immune to financial crisis; indeed, in Bourkhis and Nab, conventional banks are more resistant to the 2007-2008 financial crisis than are Islamic banks. Finally, the existence of large Islamic banks enhances the stability of the overall banking system.

Hasan and Dridi (2010) examine the trends of profitability, credit and asset growth, and external ratings for 120 banks (one quarter were Islamic) before and after the 2007-2008 crisis. Each of the countries in the sample has a dual-bank system and a considerable presence of Islamic banks. The study suggests that the profitability of Islamic banks prior to the crisis (2005-2007) was higher than that of conventional banks, but the period from 2008 to 2009 shows similar results for both banking systems. Also, large Islamic banks

4. C

outperformed small Islamic banks. The credit and asset growth of Islamic banks are higher than the rates for conventional banks during the crisis (2008)(2009). Also, external rating agencies are in favor of Islamic banks during the crisis. Parashar and Venkatesh (2010) compared conventional banks and Islamic banks in the GCC region over the 2006-2009 period based on five performance parameters: capital adequacy (capital as defined by Basel divided by risk weighted assets), efficiency (cost-to-income ratio), profitability (ROAA and ROAE), liquidity (liquid assets over total assets), and leverage (equity over total assets). The authors use equality-of-means tests. The analysis for the full study period shows that Islamic banks outperform conventional banks in terms of capital adequacy, ROAA, ROAE, and leverage. The results for before and during the crisis reveal that ROAA is significantly higher for Islamic banks than for conventional banks. ROAE do not show any differences between the two bank types during the crisis; however, this ratio was higher for Islamic banks before the crisis. Also, the analysis shows that conventional banks' ROAE, ROAA, and liquidity declined during the crisis, whereas capital adequacy ratio, ROAE, and leverage declined for Islamic banks.

Also, some studies have investigated the efficiency of Islamic banks without comparing them to conventional banks. For example, in a cross-country study, Hassan (2005) examines cost, profit, and xefficiency and finds that Islamic banks are less efficient at containing cost relative to profit generation. His results also reveal that large Islamic banks generated profit more efficiently.

5. III.

Data and Methodology consists of 348 conventional banks (Islamic windows and conversion years were not included) and the third sample are made of 70 Islamic banks, the countries which have a dual banking system in OIC countries are 23 countries, see Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3. The data are collected for 17 years; however, because a 2year moving average is used, the study period is reduced to 16 years. The data are verified and checked for errors. Regarding bank size, in the literature there are no specific amounts of assets that differentiate large, medium, and small banks. However, this study classifies a bank as large if its assets (constant 2005 USD) are greater than USD 500 million. This number is chosen because about 50% of the banks in the sample have assets that are less than or equal to USD 500 million.

The use of financial ratios is not a new way to measure efficiency and performance, as it dates back to the end of the 19th century (Horrigan, cited in Bader pair-wise comparisons for the treatment groups is analyzed using a corrected level of significance in each comparison so that the group wise error does not exceed a preselected significance level, such as ? = .01. A Levene's test is used to decide whether the population variances are likely to be equal. The p value is used in the same way as it is used in the t test; that is, reject H 0 if p < ?. The test shows that the samples are homogenized.

Six ratios (cost to income, non-interest expenses, net interest margin, return on average assets and return on average equity) are used to compare the performance of conventional and Islamic banks and are categorized into three groups: cost efficiency, revenue efficiency, and profit efficiency.

6. a) Cost Efficiency

Isik and Hassan (cited in Srairi 2010) define cost efficiency as "a measure of how far bank's cost is from the best practice bank's cost if both were to produce the same output under the same environmental conditions" (p. 48). In the present study cost efficiency is measured with cost to income ratio (CTIR) and non-interest expenses ratio (NIER). Cost to income ratio is calculated by dividing overhead by income after provisions. For conventional banks as well as Islamic banks, the items that make up a bank's costs are very similar, consisting mainly of salaries, wages, rent, and so forth. However, Islamic banks typically incur additional costs, such the costs of maintaining a shariah board. Studies find high values for the cost to income ratio for both bank types. The other ratio, non-interest expenses, is measured by non-interest expenses or overhead plus provisions to the average value of assets. This ratio expresses the expense per unit of assets. The lower this ratio, the better the bank's cost efficiency.

7. b) Revenue Efficiency

This measure indicates how well a bank is expected to perform in terms of profit relative to other banks in the same period in producing the same set of outputs (Bader et al. 2007). The ratios that make up this measure are NIM and other operating income to average assets. The NIM for Islamic banks is the income from its investment activities minus the profit distributed to its depositors and investors. This ratio is not adjusted for risk. The other operating income for conventional and Islamic banks indicates the value of other operating income generated for every dollar of assets value (Ariff et al. 2011). The higher this ratio, the more revenue efficient the bank will be.

8. c) Profit Efficiency

This measure is defined as the ratio between the actual profit of a bank and the maximum level that could be achieved by the most efficient bank (Maudos et al., cited in Srairi 2010). The most commonly used ratios to measure profit are ROAA and ROAE. However, ROAE must be interpreted with caution because evidence shows that income smoothing is practiced in many countries (Ariff et al. 2011). The ratios used in this study are shown in Table 4.

9. Category

Financial ratio Description Cost efficiency ratios Cost to income ratio (CTIR)

Overhead as a percentage of income generated before provisions. The major cost element of this ratio is normally salaries.

10. Non-interest expenses ratio (NIER)

The ratio of overhead plus provisions to the average value of assets.

11. Revenue efficiency ratios

12. Net interest margin (NIM)

Net interest revenue divided by average earning assets.

13. Other operating income (OPIR)

Calculated by dividing other operating income by average assets.

IV.

14. Empirical Results

The analysis of both samples according to bank size and location is described below.

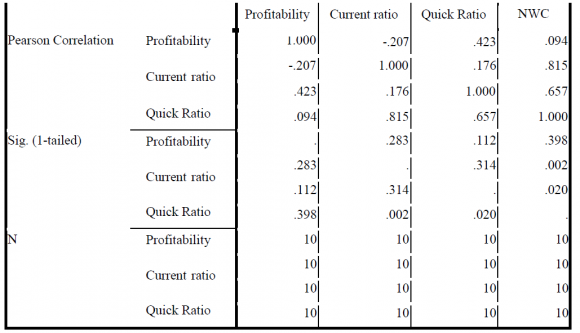

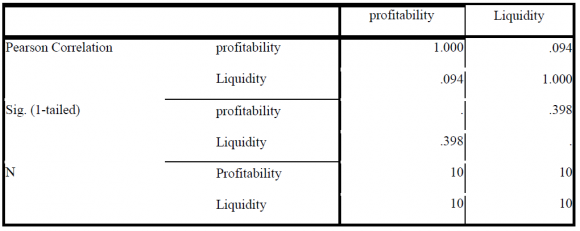

15. a) Performance of Conventional and Islamic Banks

The analysis begins with the performance of conventional and Islamic banks using the entire sample (Table 5). The t test shows mixed results when cost efficiency ratios are compared for both bank types. The cost to income ratio (CTIR) shows that conventional banks are more cost efficient, and the non-interest expenses ratio (NIER) indicates that Islamic banks are more cost efficient. This may be because Islamic banks pay higher salaries and incur extra costs (e.g., a shariah board), which can lead to a higher CTIR than in conventional banks. The NIER results suggest that Islamic banks allocate small amounts of assets to bad loans due to the nature of some of their transactions, such as ijarah and lease-back schemes, which are less risky than conventional bank loans. However, the NIM values indicate that conventional banks are more revenue efficient, which is consistent with Kaouther, Viviani and Belkacem (2011). On the other hand, there is no significant difference in the mean scores of other operating income ratio (OPIR) between conventional and Islamic banks. This contradicts findings from Hassan, Mohamad and Bader (2009) 6 shows the effect of bank size on efficiency. The means of cost-efficiency ratios (CTIR and NIER) are lower for big banks than for small banks. In addition, big banks are more profit efficient (ROAE) than small banks. Nevertheless, small banks are more revenue efficient (NIM, OPIR), and both of these results are significant at the 1% level.

16. Category Statistic

Cost Next, the effect of bank size on the performance of conventional and Islamic banks is discussed. The results in Table 7 show that large conventional banks are more cost efficient (CTIR) than small conventional banks, large Islamic banks, and small Islamic banks. However, the findings for the NIER ratio suggest that large Islamic banks are more cost efficient than large conventional banks, small conventional banks, and small Islamic banks. Also, small Islamic banks are more cost efficient than small conventional banks for both of the measuring variables-CTIR and NIER-with a significance of 10% and 1%, respectively. Next, revenue efficiency is analyzed. When NIM is the measuring variable, small conventional banks outperform large conventional and Islamic banks. Also, the t-test shows that small conventional banks is more revenue efficient (NIM). Similarly, small Islamic banks perform better than large conventional and Islamic banks. Also, the results for OPIR show that small conventional banks are more revenue efficient than large banks (conventional and Islamic). Furthermore, the mean for revenue efficiency (OPIR) for small Islamic banks exceeds the means for large conventional and large Islamic banks. Moreover, small Islamic banks perform better than small conventional banks when measured by OPIR; however, this result is not significant. The findings related to NIM and OPIR are in line with Bader et al. (2007), although their findings are not significant. This clearly shows that small banks are more revenue efficient than large banks, and this contradicts Hassan, Mohamad and Bader (2009). The results of Bader et al. (2007), albeit non-significant, show that small banks are more revenue efficient than large banks. Also, the results indicate that small conventional banks outperform small Islamic banks.

17. Global Journal of Management and Business

Using multiple comparison tests, the results of profit efficiency (ROAA) show that large Islamic banks are more profit efficient than large conventional banks, small conventional banks, and small Islamic banks. This finding is in line with Bader et al. (2007), although their results are not signifcant. On the other hand, the results for ROAE suggest that large and small conventional banks are more profit efficient than large and small Islamic banks, respectively. Also, large conventional banks are more profitable than small conventional banks and small Islamic banks. Furthermore, a t test shows that large Islamic banks are more profitable when Next, a general analysis is conducted for the entire sample of banks in the 54 countries on the basis of location (Table 8). The results from multiple comparison tests show that Asian banks are more cost efficient than banks in Africa and Middle East and Turkey, and the results are significant (CTRI). However, the NIER ratio indicates that banks in the Middle East and Turkey are more cost efficient than banks in the other regions. On the other hand, African banks are more revenue efficient (in terms of NIM and OPIR) than banks operating in Asia and the Middle East and Turkey. This in line with Bader et al. (2007) and here their results are significant in case of OPIR. In contrast, the profitefficiency results are inconclusive. Specifically, the multiple-comparison tests reveal that the banks in the Middle East and Turkey are more profit efficient than the banks in Asia when ROAA is the measuring variable but that the banks in Africa become the most profit efficient when ROAE is the variable. This in line with Bader et al. (2007), and their findings are almost significant in the case of ROAA.

For the next analysis, conventional and Islamic banks are separated (Table 9). The cost-efficiency analysis shows that Islamic banks are more cost efficient than conventional banks. However, the results vary by region: When the measuring variable is CTIR, Islamic banks in Asian countries score better than The results show that African conventional banks are more cost efficient (CTIR), whereas Islamic banks are more revenue efficient (OPIR). Furthermore, the test provides evidence that the mean scores of ROAA and ROAE are significantly better for conventional than for Islamic banks, although the results are only significant for ROAE. This identical to Bader et al. (2007) findings. Moving to Asia, the results reveal that Islamic banks have the lowest costs (CTIR and NIER); however, conventional banks have more revenue (NIM, OPIR) and profit (ROAA, and ROAE). The results for the Asian region are all significant at the 1% level. The results for banks in the Middle East and Turkey are inconclusive for cost efficiency. For instance, the findings for CTIR reveal that conventional banks are more cost efficient, whereas the NIER results show the opposite. Also, the results of revenue efficiency are not uniform: Islamic banks are more efficient at generating profit (OPIR) but not for NIM. However, conventional banks outperform Islamic banks when it comes to profitability (ROAE). The results of Middle East and Turkey region are identical to that of Bader et al. (2007) although here it is significant.

The analysis of the entire sample shows some differences between the two bank types. This contradicts Bader et al. (2007); Hassan, Mohamad and Bader (2009); and Ariss (2010). However, the present findings are in line with Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Merrouche (2010).

18. b) Performance of Conventional and Islamic Banks (Dual-Bank System)

Table 10 shows the results for Islamic and conventional banks that operated in countries with a dual-bank system. The results indicate that Islamic banks are more cost efficient than conventional banks on CTIR and NIER. This in line with Iqbal ( 2001 2007), the effect of profit efficiency is not significant, but in the present study, conventional banks are more profitable in terms of ROAE ratio, whereas the opposite is the case in Bader et al (2007). Also, the results of revenue efficiency are the same in both studies. However, the results of cost efficiency are mixed in Bader et al. (2007), but in this study the results indicate that Islamic banks are more cost efficient for both of the measuring variables.

The effect of bank size on the performance of conventional and Islamic banks in dual-bank systems is analyzed next. Table 11 summarizes these results. The multiple-comparison tests indicate that large Islamic banks are more cost efficient (CTIR) than large and small conventional banks, and the same findings are obtained for small Islamic banks. Also, both large and small Islamic banks fare better than large and small conventional banks on NIER but worse on NIM. For the other revenue ratio (OPIR), the mean value for small Islamic banks is higher than the mean value of large and small conventional banks, although those comparisons do not reach significance. In terms of profit efficiency, the table shows that there are no significant differences between conventional and Islamic banks when ROAA is the measuring variable. However, this changes when ROAE is the measuring variable, as large and small conventional banks outperform large and small Islamic banks. The results here differ from the results of the whole sample in the case of cost efficiency only. The results of the dual-banking sample are consistent, showing that large Islamic banks are more cost efficient. In the total sample, although large banks are more cost efficient, the results are mixed. Furthermore, the results obtained here are consistent with Bader et al.'s (2007) finding that large banks are more cost and profit efficient than small banks, whereas small banks are more revenue efficient (the results in the present study are significant). In addition, the present study shows that large Islamic banks are more cost efficient, whereas Bader et al. (2007) indicates that large conventional banks are more cost efficient than small conventional and Islamic banks (the outcomes for revenue efficiency are identical in both studies). The results for revenue efficiency (ROAA) are the same in both studies; however, the results for ROAE are different (for small Islamic and conventional banks). For instance the costefficiency results show mixed outcomes in Bader et al. (2007), which contrasts with our findings. Also, the ROAA results differ between the two studies, but the revenue-efficiency (NIM and OPIR) results are the same. Next, the analysis turns to the performance of conventional and Islamic banks by location for the dualbank countries (Table 12). The results for the cost efficiency is identical for that of the entire sample as Asian Islamic banks are more cost efficient when CTIR is the measuring variable. However, the results for revenue efficiency (NIM and OPIR) differ from the results for the entire sample in that here African conventional banks are more efficient, whereas in the entire sample African Islamic banks are the most efficient. For profit efficiency (ROAA) the outcome is the same, whereas for ROAE African conventional banks are the more profit efficient. When Islamic and conventional banks compared within the same region the outcome differs than that of the entire sample. For instance, African Islamic banks are more cost efficient than conventional banks, but in the analyses of the entire sample, African Islamic banks have a higher mean CTIR and NIER than their counterparts. The results for revenue efficiency do not show significant differences between the two banking systems (in Africa), but in the entire sample Islamic banks are more revenue efficient for both of the measuring variables. The findings for profit efficiency in both samples are identical, which confirms that conventional banks are better than Islamic banks at generating profit in Africa. There is no change in the results between the total sample and the dual-bank sample when it comes to Asia, although the significance levels are weaker for the dual-bank sample. Regarding the Middle East and Turkey, the dual sample shows that Islamic banks are more cost efficient (CTIR and NIER), and this contradicts Olson and Zoubi (2011). In the present study, there is no variation by bank type for the entire sample. The revenue-efficiency outcome is the same in both samples. However, profitability shows significant changes in the dual-bank analysis; specifically, in the whole sample conventional banks outperform Islamic banks (ROAE), but the ROAE means are not significantly different for conventional and Islamic banks in the dual-bank sample. For the ROAA ratio, the results in both analyses indicate that Islamic

19. Volume

20. Bank

21. Conclusion

The results indicated that, on average, the Islamic banks in both samples are more cost efficient than the conventional banks. Also, based on the results of cost efficiency it can be said that Islamic banks can reduce their CTIR by controlling their operational expenses and conventional banks can reduce their NIER with better risk management. Moreover, the mean variable, the conventional banks outperform the Islamic banks. In contrast, the results of the other revenueefficiency variable (OPIR) show that the Islamic banks are more efficient. This could mean that Islamic banks depend more on investments contracts (e.g., murabaha,

The effect of location on Islamic and conventional bank performance (dual-banking sample) are significant in this study but not in Bader et al. (2007). For example, the results for cost efficiency (CTIR and NIER) here indicate that Asian Islamic banks are the most cost efficient, whereas Bader et al. (2007) shows mixed results. Also, the results of revenue efficiency are different; in Bader et al. (2007) African Islamic banks are the more revenue efficient, but in the present study African conventional banks are the more revenue efficient. The results for revenue efficiency are the same in both studies, but in the present study they are

The results for profitability are in line with Olson and Zoubi (2008) and Olson and Zoubi (2011). banks are more profitable, but the results are only significant (although weak) for the dual-bank sample. banks, and small conventional banks when ROAE is the measuring variable. In addition, the results show that small Islamic banks are more cost efficient than small conventional banks, but the latter are more revenue and profit efficient. Although small Islamic banks should be encouraged to merge, in general the results here are almost identical in both of the samples.

Also, the analysis shows that, on average, Asian Islamic banks are more cost efficient than all other banks (in Africa and the Middle East and Turkey), conventional or Islamic. The revenue-efficiency analysis reveals that African banks are more revenue efficient than banks in other regions. However, the results differ between the two samples: Islamic banks prevail on NIM and OPIR in the total sample, whereas conventional banks are stronger on both outcomes in the dual-bank sample. With respect to profitability, Islamic banks in the Middle East and Turkey are the most profitable in both samples when ROAA is the measuring variable. On the other hand, the ROAE variable shows mixed results. In the dual-bank sample, conventional banks in the Middle East and Turkey are the most profitable. For the entire sample, conventional banks in Africa are the most profitable. All of these results are significant at the 1% level.

Furthermore, the results related to Asian region reveal hat conventional banks are more revenue and profit efficient compared to its counterpart. On the other hand, the results of the African region show, in large, that Islamic banks are more cost and revenue efficient than conventional banks, however its profit efficiency is lower. Meanwhile, the efficiency analysis of conventional and Islamic banks in the Middle East and Turkey region did not give a conclusive results concerning revenue and profit efficiency, this because the outcome of the both samples (whole and dual-bank) are different. However the results of cost efficiency generally indicate the Islamic banks are more cost efficient.

It is worth noting that when only Islamic banks in the three regions are compared, African banks are the most revenue efficient, Asian banks are the most cost efficient, and banks in the Middle East and Turkey are the most profitable; these findings are consistent with Bader et al. (2007). This is true for the total sample and the dual-bank sample. When conventional banks are compared with one another, for the most part there are no significant variations by region. This shows that location plays an important role in the performance of the Islamic banking industry. This could be attributed to regulations, differences in GDP growth and GDP per capita, development of capital markets, and level of economic activity. Also, the analysis of both samples confirmed that Islamic banks were superior to conventional banks in controlling costs. However, there is a room for Islamic banks to improve their revenue efficiency. On the other hand, the results for profit efficiency are not conclusive-Islamic banks do better on ROAA, and conventional banks do better on ROAE. But, if income smoothing practices taken into account it can be said that Islamic banks are more profitable.

Finally, the results of the entire sample are almost identical to Bader et al. (2007), but both are slightly different from the results of the dual-banking system sample, where Islamic and conventional banks are compared based on size and location. No. Country/year 1992Country/year 1993Country/year 1994Country/year 1995Country/year 1996Country/year 1997Country/year 1998Country/year 1999Country/year 2000Country/year 2001Country/year 2002Country/year 2003Country/year 2004Country/year 2005Country/year 2006

| Year |

| Volume XVI Issue I Version I |

| ( ) |

| Global Journal of Management and Business Research |

| 28 |

| efficiency Revenue efficiency Profit efficiency | |||||||

| CTIR | NIER | NIM | OPIR | ROAA ROAE | |||

| Big banks | M | 150.35 | 2.96 | 3.25 | 1.70 | 1.05 | 12.26 |

| SD | 101.38 | 3.56 | 2.97 | 1.54 | 2.51 | 6.70 | |

| Small banks M | 189.69 | 4.87 | 4.68 | 3.45 | 1.16 | 11.03 | |

| SD | 167.66 | 4.79 | 4.74 | 3.16 | 4.29 | 10.08 | |

| t-test | 10.89 | 17.29 | 14.65 | 28.65 | 1.31 | 5.55 | |

| 2016 |

| Year |

| Volume XVI Issue I Version I |

| ( ) C |

| Research |

| Cost efficiency | Revenue efficiency | Profit efficiency | |||||||

| Region Statistic | CTIR | NIER | NIM | OPIR | ROAA | ROAE | |||

| Africa | M | 220.18 | 5.53 | 5.24 | 3.94 | 1.23 | 13.00 | ||

| SD | 163.88 | 4.10 | 4.06 | 3.01 | 1.63 | 10.70 | |||

| Asia | M | 147.88 | 3.86 | 3.40 | 2.46 | 1.01 | 11.00 | ||

| SD | 114.98 | 5.80 | 3.34 | 2.49 | 1.85 | 8.09 | |||

| Middle | M | 149.28 | 2.71 | 3.51 | 1.64 | 1.27 | 11.47 | ||

| East and | SD | 112.52 | 2.20 | 4.25 | 1.64 | 1.23 | 7.00 | ||

| Turkey | |||||||||

| ANOVA p Between | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||

| groups | |||||||||

| Cost | Revenue | Profit | |||||||

| efficiency | efficiency | efficiency | |||||||

| Bank category | Statistic | CTIR | NIER | NIM | OPIR ROAA ROAE | ||||

| African conventional M | 215.65 | 5.58 | 5.15 | 3.84 | 1.23 13.29 | ||||

| SD | 153.43 | 4.16 | 3.751 | 2.99 | 3.10 11.00 | ||||

| African Islamic | M | 272.22 | 4.91 | 5.66 | 5.00 | 1.13 11.05 | |||

| SD | 211.19 | 2.91 | 6.02 | 3.23 | 1.83 | 7.76 | |||

| t-test | 4.59 | 1.71 | 1.66 | 5.51 | 0.42 | 2.64 | |||

| Asian conventional M | 149.55 | 4.00 | 3.50 | 2.60 | 1.06 11.10 | ||||

| SD | 118.05 | 6.12 | 3.41 | 2.66 | 2.75 | 7.94 | |||

| Asian Islamic | M | 109.44 | 2.34 | 2.06 | 1.31 | 0.21 | 6.06 | ||

| SD | 128.31 | 1.50 | 2.05 | 0.85 | 1.55 10.54 | ||||

| t-test | 3.63 | 2.64 | 4.52 | 5.777 | 3.33 | 6.31 | |||

| Middle East and | M | 153.30 | 3.01 | 3.97 | 1.60 | 1.25 11.74 | |||

| Turkey conventional | SD | 114.05 | 2.47 | 4.85 | 1.73 | 3.13 | 7.32 | ||

| Middle East and | M | 167.91 | 2.33 | 2.80 | 2.04 | 1.37 10.60 | |||

| Turkey Islamic | SD | 151.83 | 1.50 | 1.94 | 2.10 | 1.73 | 7.23 | ||

| t-test | 2.11 | 4.85 | 4.82 | 4.65 | 0.75 | 2.76 | |||

| ANOVA p | Between | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| groups | |||||||||

| Cost | Revenue | Profit | ||||||

| efficiency | efficiency | efficiency | ||||||

| size | Category | Statistic | CTIR NIER | NIM | OPIR ROAA ROAE | |||

| Big Conventional | M | 158.58 | 3.31 | 3.60 | 1.79 | 0.84 | 11.18 | |

| bank | ||||||||

| SD | 121.72 | 4.32 | 4.16 | 1.71 | 4.82 | 7.25 | ||

| Islamic bank M | 137.91 | 2.45 | 2.51 | 1.98 | 1.98 | 9.38 | ||

| SD | 109.93 | 1.63 | 1.90 | 2.26 | 2.15 | 7.32 | ||

| t-test | 3.34 | 3.80 | 5.48 | 1.25 | 0.78 | 2.96 | ||

| Small Conventional | M | 155.15 | 3.32 | 3.61 | 1.18 | 0.86 | 11.15 | |

| bank | ||||||||

| SD | 117.11 | 4.33 | 4.17 | 1.72 | 4.84 | 7.22 | ||

| Islamic bank M | 138.17 | 2.46 | 2.49 | 1.99 | 1.02 | 9.35 | ||

| SD | 109.66 | 1.63 | 1.88 | 2.61 | 2.14 | 7.35 | ||

| t-test | 2.85 | 3.84 | 5.64 | 2.14 | 0.73 | 2.98 | ||

| ANOVA p | Between | .000 | .000 | .000 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.01 | |

| groups | ||||||||

| Cost efficiency | Revenue efficiency Profit efficiency | ||||||

| Category | Statistic | CTIR | NIER | NIM | OPIR ROAA ROAE | ||

| Conventional | Mean | 182.09 | 3.30 | 3.60 | 1.80 | 0.85 | 10.00 |

| banks | |||||||

| SD | 121.97 | 4.30 | 4.15 | 1.72 | 4.80 | 35.74 | |

| Islamic | Conventional | Total no. of | ||

| No. | Country | banks | banks | banks a |

| 1 | Afghanistan | 3 | 3 | |

| 2 | Albania | 11 | 11 | |

| 3 | Algeria | 1 | 12 | 13 |

| 4 | Azerbaijan | 16 | 17 | |

| 5 | Bahrain | 6 | 6 | 17 |

| 6 | Bangladesh | 5 | 27 | 33 |

| 7 | Benin | 8 | 8 | |

| 8 | Brunei | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 9 | Burkina Faso | 9 | ||

| 10 | Cameroon | 11 | 11 |

| 35 Nigeria | 2 | 4 | 6 10 12 13 13 14 15 18 18 17 16 18 18 19 18 | ||||||||||||||

| 36 Oman | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 37 Pakistan | 3 13 13 16 17 17 17 17 17 16 16 20 22 25 29 29 29 | ||||||||||||||||

| 38 Palestine | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 39 Qatar | 0 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 40 Saudi Arabia 1 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 11 11 11 11 | |||||||||||||||||

| 41 Senegal | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 42 Sierra Leon | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| 43 Sudan | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 14 14 17 15 11 14 18 23 23 | |||||||||

| 44 Suriname | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 45 Syria | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 7 11 11 | ||

| 46 Tajikistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 47 Togo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 48 Tunisia | 4 13 13 13 13 13 15 15 16 16 15 14 14 15 15 15 15 | ||||||||||||||||

| 49 Turkey | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 22 22 26 30 31 35 34 35 34 34 | ||||||||||

| 50 Turkmenistan 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 51 Uganda | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 10 11 11 11 11 11 11 11 11 | |||||||||

| 52 UAE | 1 14 16 16 17 17 18 18 17 18 20 20 19 20 20 20 20 | ||||||||||||||||

| 53 Uzbekistan | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 8 11 11 10 10 11 8 | ||||||

| 54 Yemen | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 84 235 280 321 361 381 399 441 466 490 507 532 553 588 605 625 597 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2007 2008 |

| No. Country/year 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 Algeria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 Bahrain | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 3 Bangladesh | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 Brunei | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 Egypt | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 Gambia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 Indonesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 Iraq | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 Jordan | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 10 Kuwait | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 Lebanon | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 12 Malaysia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 11 11 11 | |||

| 13 Mauritania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 Pakistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 15 Palestine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 Qatar | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 17 Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 18 Senegal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 Syria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 20 Tunisia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 21 Turkey | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 22 UAE | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 23 Yemen | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 3 13 13 18 19 21 24 25 25 30 37 40 41 50 61 66 67 | ||||||||||||||||