1. Introduction

pas have existed since ancient times. Fans of "taking the waters" or, more recently, wellness seekers have been the target of reinvented business modalities of dealing with the human need for getting away from it all or the desire to be forever young.

The International Spas Association (ISPA 2002(ISPA -2008) ) defines spas as places meant to provide wellbeing through professional services that allow the renewal of mind, body and spirit. The current and predominant spa business model is the amenity spa (the "wellness area" is an ancillary service), due to its offering of a more comprehensive experience than the traditional destination spa (Mak et al, 2009;Keri et al, 2007). Travellers whose main motivation is not wellness (those who usually attend amenity spas) represent 87% of wellness tourism trips (Stanford Research Institute, 2013). The Global Wellness Institute and the Stanford Research Institute (2013) emphasize that the wellness or spa industry accounts for $438.6 billion, which represents 14% of all domestic and international tourism expenditures.

Several organizational theories have dealt with how industries or firms evolve from a dynamic (the PLC or S Curve, Lewitt, 1965Lewitt, -1966) ) or a static (Five-Forces Framework, Porter, 1980; Business Models, Zott et al., 2011) viewpoint. Anita Mc Gahan (2000) stresses that both approaches are not enough to explain industry evolution and predict profitability. This is related to the Author: e-mail: [email protected] pattern of innovation present in each industry. A similar position to Mc Gahan's is maintained by Abernathy & Clark (1985), who affirm that industries grow according to four different models of innovation which are closely linked to different managerial environments and evolution processes.

The study of the spa industry according to the PLC and business model theories has evidenced that both constructs have not entirely elucidated its evolution (Vazquez-Illa, 2014).The kind of innovation present in the spa industry is clearly pointed out as the reason for its high competitive intensity and the industry's partial nonconformity to PLC theory. Early entry into the industry, size, and the achievement of a dominant design at maturity does not deter new entrants which eventually increases rivalry among incumbents. The competition is further reinforced by the fact that real estate investments are not easily discarded when confronted with a crisis (PKF, 2009). New entrants are attracted to the industry by the apparent ease in gaining a position in the market (Vazquez-Illa, 2014) as a result of the short-lived dominant designs in the industry.

All the mentioned factors lead to pose the question of how innovation shapes the spa industry and how it determines its evolution. This paper aims to answer this question.

Employed methodologies are literature review, an analysis of a sample of European and American spas, and an in-depth case study on a European spa company. Research methodologies include both primary and secondary web-based approaches. More than 50% of Spain's resort spas or spa resorts, plus the ten most distinguished European and North American destination spas have been subject to direct observation.

The use of qualitative methodologies is a result of the embryonic state of research on this sector and, consequently, the lack of a commonly-shared theory to aid in the explanation of the whole phenomenon that would justify deductive methods. Abercrombie et al. (1980), Yin (1984), Eisenhardt (1989) stress the usefulness of the casestudy in the preliminary stages of research because it allows the development of hypothesis that eventually may be proved with a higher number of cases.

Although qualitative methodology is mainly reserved for the development of theory by using the inductive method, this does not deny the principle Consequently, the work is structured in the following way. First, theoretical propositions are developed. Second, the illustrative case of the Company Terma Europa Spas is subject to analysis to unveil how the company deals with innovation. Third, a discussion on spa industry conformity to the propositions is carried out. Fourth, innovative proposals on spa business models are introduced. Finally, conclusions are drawn.

Conclusions underscore that easy to imitate market niche innovation (Abernathy& Clark, 1985) shapes the industry, bringing about a scenario of high intensity competition due to the low entry barriers. As a result, early entry and size do not become crucial factors in imposing a dominant design and defending a position in the market since innovation is mainly introduced by new entrants. On the other hand, market-pull innovation rules the industry because of its multiple customer contacts. The design of low-cost and low-luxury models whose choices incorporate the industry's critical factors of success (spa design with more emphasis on collective use, standardization of service providing, and product bundling) seems to be the best way to flee the vicious spiral of intense rivalry.

2. II.

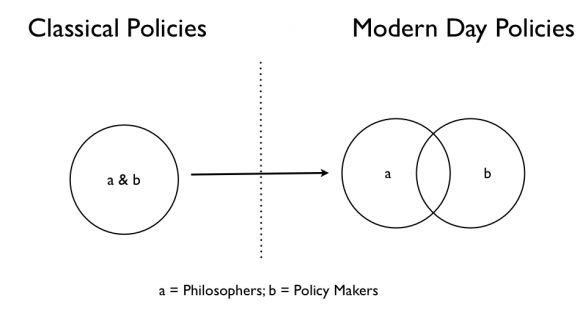

3. Theoretical Propositions a) Proposition 1

Early innovation comes as a consequence of companies concentrated in geographical clusters, which makes the quick diffusion of tacit knowledge (Audretsch and Feldman, 1996) possible. Tidd et al. (2005) define innovation as changes affecting product, process, position or paradigm, i.e., changes in the underlying mental models which frame what the organization does. They highlight the difference between incremental or evolutionary innovation, and radical, disruptive or paradigmatic innovation. Paradigmatic innovation derives from Kuhn's reflections on the structure of scientific revolutions (1962), stating that a paradigm is what members of a scientific community share. Kuhn's notion of paradigms as a set of expected solutions to accepted problems is also applied to the definition of technological paradigms (Peine, 2008). It turns out from its application that there are industries in which different paradigms coincide and paradigm communities can cooperate to make innovation happen.

4. b) Proposition 2

New competitors are the advocates of product innovation at the preliminary stages while present incumbents are the driving force of process innovation at the maturity stage (Klepper, 1992(Klepper, -1996(Klepper, -1997;;Mueller and Tilton, 1969;Utterback and Suarez, 1993;Plog, 2001;Agarwal and Audretsch, 2001).

The lack of a commonly-accepted design at preliminary stages tends to foster product innovation outside the standards and procedures of present incumbents, favouring new competitors. However, when a design is widely accepted at the maturity stage, innovation tends to focus on the production process rather than on the product itself which enhances incumbent position when faced with new entrants.

5. c) Proposition 3

A business model with open innovation makes the task of detecting changes in the environment easier (Kuhn, 1962;Abernathy and Clark, 1985;Durand, 2001;Chesbrough, 2007;Chesbrough et al., 2007;Peine, 2008).

Many outside changes may question a business model viability, especially when an industry reaches its carrying capacity; hence, the importance of designing models with open innovation or the ability to incorporate innovative activity developed by other companies.

6. d) Proposition 4

Market-pull innovation characterizes the service sector and, especially, the hospitality industry (Narver and Slater, 1990;Mansury and Love, 2007;Hall et al., 2009;Trigo, 2009;Hjalager, 2010).

The significant number of customer contacts in the spa industry allows for the development of close ties with the customer which eventually brings about demand-pull innovation through the detection of articulated and even latent market needs.

7. e) Proposition 5

The emergence and duration of stages is a function of the way an industry shapes innovation (Abernathy and Clark, 1985 Market niche innovation is easily subject to imitation due to its reduced impact on present technology. As a result, it does not allow for the development of a sustainable competitive advantage. Eventually, it only triggers an increase in industry competition with the subsequent reduction of income.

8. III.

Case-study Analysis a) Justification TermaEuropa was selected for study due to its consideration as the first hotel spa company that was launched in Spain (2001) to cater to emerging segment needs (the relaxation segment). The company represents the transition from the older paradigm to the new one, the wellness and well-being paradigm.

It involves a case study with multiple levels of analysis. Its justification derives from Yin's (1984) and Eisendhardt's (1989) defence of the selection of a single case with multiple levels of analysis in order to better illustrate the occurrence of a phenomenon in its preliminary stages.

Eisendhardt (1989) points out that case-study methodology combines ways of gathering data such as: analysis of company files and records, interviews, surveys and observation. In the case of TermaEuropa, the instrument used was analysis of company files and records with qualitative and quantitative information, observation and empirical evidence.

The rigor of the analysis is demonstrated by the observation of the principles of internal validity: there is a cause/effect relationship between the company's strategy and the achieved results. Construct validity: the variables subject to study are set forth and described. External validity: analytical generalization based on the theoretical propositions is possible; and reliability: the absence of random error is assured through the possibility of examination of original documents by other researchers (Campbell and Stanley, 1963).

9. b) Innovations

The company's success is undoubtedly a function of its relentless effort to innovate as a way to remain competitive. All the company's innovation derives from its relationship with the customer. The customer's opinions and latent demands are subject to scrutiny though a monthly survey from the beginning of operations. Surveys address, in a consistent way, quality and marketing issues, allowing TermaEuropa's executives to make decisions that closely follow its target markets; this provides a high probability for success.

Table 1 presents some of the innovations implemented according to each category. The company itself can be considered its greatest product innovation. Never before had a hotel spa chain been launched in the Spanish market under the same brand with common procedures and operations while having different hotel designs in each location. Offering packages well focused on the determinant motivations of customers is the second product innovation. Reviewing TermaEuropa's company files and records one may clearly establish the link between target market motivations and its product offerings meant to exceed expectations: Feeling well.

Relieving an ailment, being pampered, and getting away from it all? Our treatments aim at all of these pleasurable sensations for our guests. Therefore, we train our therapists to do not only a good job but also to convey tranquillity and make our client feel as if they were the only one.

10. PRODUCT INNOVATIONS MARKETING INNOVATIONS

The company itself Marketing Intelligence Link of motivations with target markets-product/service offering and programmes to relax, look better and feel well

11. Relationship marketing

12. Product presentation Communications

13. PROCESS INNOVATIONS ORGANIZATION INNOVATIONS New call center and its impact on customer quality perception

Implementation of a revenue management system

14. Standardization of service New compensation policy for hotel general managers

15. Innovations meant to increase demand

16. Innovations meant to reducing costs and increasing production capacity

rid of stress and ease our ailments, reproducing an environment that conjures up images of remote paradises, in silence perhaps broken only by the sound of water.

It is precisely the thermal and mineral water used in many of our establishments what differentiates them from the rest. After having a thermal bath or a shower, or after being massaged under the water, the skin is soft and brilliant, and our body has assimilated some of the minerals in the mineral water.

Sleeping, perhaps dreaming. A large 2x2 bed which lets us sleep and dream. A good shower, warm decoration, where elegance and efficiency coalesce in aharmonious ensemble. Our complimentary bath robe, free mini-barand amenities. You only have to sit in front of the window and contemplate the countryside.

Always walking. Guided hiking is the most demanded activity by our clients. The location of our spa resorts surrounded by nature makes it possible to enjoy this activity intensely.

Meeting is a prize in health. An important decision taking, a well-deserved break for the team, a convention, an incentive trip? Find out how to achieve unbeatable teams, making them live a memorable experience.

The call for target market motivations depicted above, is complemented with an array of programmes that translate expectations into benefits to be obtained with multiple treatments: Packages: Relaxation-Beauty-Therapy

To unwind, getting away from it all, feeling the thermal water's sedative powers.

To look better, achieving soft skin and a fresh look with beauty treatments reinforced by mineral water. To feel well, relieving numerous ailments.

The traditional product offering at spas is not overlooked but presented in a different way under the name feeling well that matches perfectly with its primary segment's (the relaxation segment) broad concept of health.

Product innovations are also derived from new product offerings under the terms "relaxation" and "beauty," unknown in most European spas until the dominant paradigm changed in the 1990s.

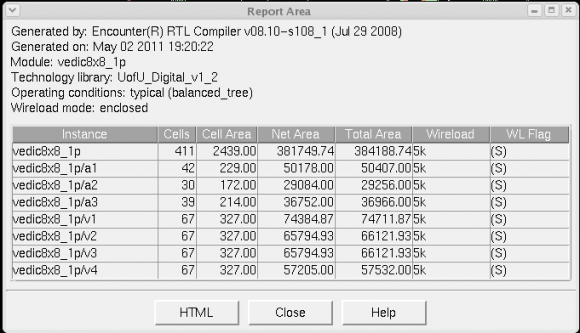

ii. Process Innovations An efficient running of daily operations underlies the success of TermaEuropa. Due to the company's belonging to a market that was emerging, heavily fragmented and less professional, the introduction of several management tools which were highly extended in other sectors has evolved into a phenomenon of The first process innovation is the restructuring of the reservations system. Until the emergence of TermaEuropa, the usual procedure was to collect reservations in manual form. Customers could make hotel reservations, but not the reservation of treatments. This hindered efficient organization of service providing (timely allocation of personnel and resources). When clients at hotels wanted to contract a service, they were told to remain in their rooms waiting for a phone call from the treatment area, or even worse, to idle in the waiting room for an indefinite period of time.

In the industry, it was widely considered that it was not possible to reserve a treatment room before the client's arrival, since the treatment had to be decided upon by the spa physician. In fact, Micros-Fidelio, the most extended software in the hotel industry, did not distribute spa management software until the late 1990s. Hence the first spa management software had to be customized to resort needs.

The implementation of a call centre with highly trained operators in the hotel spa field produced a positive impact on the TermaEuropa project. In one call, customers could reserve both room and treatments and were advised what program to buy according to their objectives.

The standardization of service providing constituted the second critical process innovation. Until then, the extended belief was that it was not possible to standardize treatments like massages in the way it is done in other areas of hotel service. The experience of TermaEuropa shows that it is possible.

Massage standardization implies that therapists must understand they are generating an experience for the customer where everything counts: a warm welcome, what it is said, how it is said, the atmosphere, and the way of massaging the client. The urban legend saying that it is impossible to produce a massage equal to another one since a pair of hands are not equal to another is hardly true. This fact does not belie the principle that operating procedures may be established to determine how hands have to move, the exact pressure exerted or the points to be covered. This obviously requires sound training sessions for therapists. Here, the advantages are paramount: the company may focus on selling time since the customer does not notice any difference among therapists, staffing becomes easier, workload is adequately distributed, and, eventually, labour costs are reduced for the establishment.

Examining TermaEuropa's operations manual is highly illustrative of the steps taken in an effort to standardize the service: Massage room preparation before the service: Light should be dimmed to recreate an intimate space

The décor and design of our facilities don't play a minor role in this whole process seeking to help us get innovative. This has triggered a virtuous effect in all the company departments.

Temperature must be adapted to the client's comfort The room must be equipped as established Information about workload Customer service Procedure to welcome the client How to communicate the client the procedure to follow How to apply the massage Client's farewell iii. Organizational Innovations Two organizational innovations are outlined: the implementation of a revenue management strategy at La Alameda Day Spa (one of Terma Europa's properties), and the linkage of Terma Europa's management salaries to the company's productivity.

The application of revenue management within the spa industry is still in its infancy. However, it is an innovation with the capacity to generate revolutionary effects if being applied from a strategic viewpoint, allowing for value capture for the company together with value creation for the customer (Kimes, 2009).

Revenue management, yield management at first, was born in the field of the airline industry as a way of obtaining the maximum possible yield per available seat. The hotel industry incorporated this tool later on as a way of obtaining better performance per available room, even per available seat in a restaurant. In essence, it is about selling the adequate capacity to the adequate customer, at the right moment and at the right time.

Hotel rooms, restaurant seats, and treatment rooms (and available spaces for sale at activity pools) are perishable inventories. In these kinds of industries, the lack of occupancy or sale of an available capacity entails two types of costs (Kimes, 2009): a labour cost from unused workforce and an opportunity cost from the income lost as a result of the lack of occupancy of available capacity for sale.

The first stage in developing a revenue management strategy consists of evaluating demand.

Figure one describes how the demand evolves at La Alameda Day Spa by time of the day and week day. The representation of the data reveals some conclusions regarding demand behaviour and facilitates the measures to be taken in order to obtain a better yield in those facilities.

Source: Terma Europa's company files and record The demand analysis is fully developed, covering different services, times and days in order to develop a guide to help in forecasting demand and correctly allotting human resources and products. This strategy implementation has positively impacted the operation's bottom line, discarding the previously ubiquitous general discounting that was clearly damaging the spa's returns, and endorsing fenced rates.

Herein follows some examples of how the company implemented the revenue management strategy on the internet. Criteria for implementing online reservations according to revenue management protocol for the Roman Bath and the Activity Pool:

The client can make reservations on the following products (treatment reservations will also be available at a later date): Roman Bath and Activity Pool.

All the published rates are VAT included. There are different prices according to days/times/services. Management may change the rates.

To obtain a discounted rate, there is no time span for these two facilities, however, for treatment reservations some time period will be demanded to allow for adequate staffing; the reservation should have been entirely paid; reservations must be made through the web.

Cancellation policy: there is no possibility to cancel, only to move the reservation to another day/time if available.

Table 2 shows a display of prices and services offered throughout the week under the principles of revenue management. Rates are fenced to specific times to allow for product differentiation and targeting of different market segments.

Table 2 : Fenced rates for the activity pool according to time and weekday Source: Termaeuropa's company files and records Another organization innovation with a positive impact on productivity is the linkage between the salary compensation of hotel spa general managers to the fulfilment of an array of financial and quality objectives (see table 3).The study of the Ratios of Control for TermaEuropa hotel spa General Managers shows Kaplan and Norton's influence on TermaEuropa's upper management in the sense that financial results are not the only critical aspect to be considered when analysing companies. Staff capacity, the fulfilment of established procedures and client satisfaction are also key factors for success. Financial data give an overall picture of the company at the present time; however, quality ratios anticipate future value creation for the shareholders. General Managers obtain a quarter of their bonuses if their customers rate their properties 4 out of 5 on average, or express satisfaction more than 80 per cent of the time. Their bonuses are also dependent on financial concerns. The so-called magic formula stipulates that cost of sales must not go beyond 14 percent of net sales (5 percent in the case of a day spa); wages should be 34 percent of net sales or less; the rest of non-assigned operating costs should not go beyond 20 percent of net sales. Finally, salary compensation is also determined by internal quality surveys and independent external surveys regarding tricky issues such as the presence of bacteria at water sources or the kitchen.

Instruments used for data collection in order to establish manager bonuses are: the satisfaction survey, the tabulation system and the evaluation form. Next, the 2007 satisfaction index for TermaEuropa spas and the standard customer survey are displayed as figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Source: TermaEuropa's company files and records Por favor, valore del 1 al 5 cada uno de nuestros servicios. Siendo 1 la nota más baja y 5 la más alta. Please, fill in the blank boxes with your marks for our service, being 1 the lowest score and 5 the highest one.

L L K J J L L K J J These innovations take place in the field of marketing intelligence, relationship marketing and communications. Marketing intelligence emphasizes that knowledge of market trends, consumer viewpoints and competition are key factors for increasing customer data bases to reinforce links with the customer and promote their loyalty. It is derived from the fact that a company's customer data base constitutes its most valuable asset (Lewis and Chambers, 1989).

Communication is one of the marketing-mix tools meant to tangibilize the product/service offering (Renaghan, 1981). Some instances of the communication strategy followed by the company are reproduced to illustrate its business concept. The brochure of figure four shows how the company attempts to connect with its primary target market's expectations: a massage and water treatment to encourage sales. England, the leading country in the Industrial Revolution in the manufacturing sector, is also a country at the forefront of the leisure industry, developing the first thermal spa resorts in the late 18th century (Bacon, 1997). Spa resorts were concentrated in that country reaching the figure of 200 units by the mid-19th century. This reinforces proposition number 1 that claims preliminary innovation tends to appear in geographic clusters.

renewed German spa towns. New entrants are also the protagonists of product and process innovation when amenity spas appeared for the first time in the last quarter of the 20th century; when the wellness paradigm prevails, most of the companies that capitalize on relaxation trends are new entrants from the hotel sector and without links to the hospitality sector (Weisz, 2001; Orbeta Heytens and Tabacchi, 1995).

17. c) Proposition 3

Proposition number 3 holds true through recent history. The growth stage of the industry extends up to the last quarter of the 19th century when maturity comes and, eventually, declines due to the questioning of the Hygienic movement -whose principles fostered the change of environment, like the one typically experienced at a stay in a spa, as the best remedy for b) Proposition 2 However, contrary to proposition number 2, process innovation was carried out by new entrants, the any disease-and the rising competition of beach resorts (San Pedro, 1994).

The decline was not overcome until the 1960s in the US (Tabacchi, 2010). The new destination spa did not have anything to do with its predecessor (radical innovation), nor were its customers the same, nor were its treatments, putting aside thermal waters and opting for strict diets and strenuous exercises as the way to beauty. The radical US change may be considered an architectural one in the sense depicted by McGahan (2000) because the principles of the thermal paradigm are subject to substitution.

In Europe, however, the traditional destination spa survives, slowly incorporating (incremental innovation) some of the services provided by American spas (Bywater, 1990; Intelligent Spa Pte Limited, 2009). The influence of the fitness craze is more evident in the increasing number of fitness day spas that started to open since then.

The fitness destination spa model was gradually replaced by the amenity spa business model in the US in the 90s (evolutionary innovation) (Orbeta Heytens & Tabacchi, 1995;Van Putten, 2003).

In Europe, the transition from the pseudotraditional destination spa to the amenity spa business model took place in a more drastic way, bringing about a new paradigm (radical innovation) (Bell & Vazquez-Illa, 1996). The spa sector experienced radical innovation due to the questioning of the thermal spa paradigm in order to open industry establishments to younger clients yearning for relaxation treatments. This was very distant in its concept and execution from the traditional rheumatic treatments meant for the older segments.

Only those spa business models with open innovation were able to adapt its value proposition to the emerging relaxation segment, both in US or Europe (Les Dossiers de la Lettre Touristique, 1992; Bywater, 1990;Orbeta Heytens and Tabacchi, 1995). The analysis of the TermaEuropa Spas Company clearly supports this.

18. d) Proposition 4

Most innovations in the industry are of a demand-pull type (proposition 4), as a consequence of multiple customer contacts (McNeils and Ragins, 2005; Montenson and Singer, 2003). Demand-pull innovation presides over the evolution of the industry as previously demonstrated in the case study.

Table four displays several innovation proposals relating to the spa industry, all of a demand-pull type. The list differentiates between innovations aimed at increasing product demand or marketing innovationsand those meant to improve production capacity and cost reduction -process and organization innovations (OECD/European Communities, 2005)-.

Some product innovations indirectly generate cost reductions, such as in the case of spa suites, short treatment menus or low-cost models. Within marketing innovations, the creation of theme packages stands out. It is worth noting the implementation of revenue management strategies as an organizational innovation, and the redesign of service providing for emerging segments as process innovation, among innovations aimed at increasing production capacity. kind of innovation present in the industry -market-niche innovation, where mere refinements in technology may bring about new linkages with the market and affect incumbents' position while reducing entry barriersdetermines the current intensity of competition and the shorter duration of life cycle stages. Furthermore, this kind of innovation is easily subject to imitation due to its reduced impact on present technology (Abernathy and Clark, 1985), which prevents companies from gaining a sustainable competitive strategy based on the features of their innovations. The turbulent state of the industry and its predominant business model characterized by inadequate product design, on the supply side, and confusion or/and discontent, on the demand side (Vazquez-Illa, 2014), are explained by market-niche innovation that shapes the spa industry. This kind of innovation is derived from a specific managerial culture which is very dependent on their ties to customers (demand-pull innovation characterizes the industry as stated previously), allowing for constant instability regarding the dominant design. Since innovations are not of an architectural scope, it is easier for new entrants to foray into the market through mere refinements in technology which brings about new ties to customers.

V.

19. Proposal of new spa business models

As a result of the preceding analysis, two new business models are proposed that incorporate and further develop many of the innovations pointed out in previous sections.

Low-cost concepts have lately been at the forefront of the business arena, and in every single sector, as a general attempt to determine operating models allowing for good quality products at affordable prices and, therefore, outstanding profits (Montenson & Singer, 2003;Marti, 2010). Furthermore, Johnson (2010) states that there is a business opportunity for a company capable of providing IKEA-style hospitality: a company that is highly focused on its target market permitting differentiating and affordable service providing.

In the last two decades, most amenity spas have mistakenly reproduced the destination spa business model without counting on its core segment: which are followers of a holistic approach to the use of spa services and, as a consequence, potent consumers of a variety of treatments. The results of that strategy have globally been very poor, mainly for those hotels without a local market to target. Most hotel customers are peripheral spa consumers (they never book a treatment) or, that being the case, it is a relaxation related service, i.e., a plain massage (Tabacchi, 2010;Keri et al, 2007). As a result, as a norm, developing large establishments with an array of services fully resembling the destination spa business model is destined for failure.

this is what has prevented them from fully taking advantage of social trends in fitness and relaxation. The tendency to replicate the destination spa model has brought about treatment rooms equipped with medical appliances nobody uses or sophisticated baths subject to unending amortization periods. At the same time, collective areas are scarce when their return rate is notably superior to individual treatments' rate, whose ratio of one employee per customer becomes a heavy burden to assume. The growth stage of the spa product cycle has allowed it, however, to capitalize on fitness and relaxation trends, although something is changing on the horizon.

20. a) Low-cost spa

The proposed low-cost spa (figure 7) is a concept designed to cater to peripheral consumers' needs (the fact of being a secondary segment comes from its lack of conscious empathy with the industry's philosophy, not because its numbers are not critical at vacation times). This customer mainly goes to spas at vacation periods and never books a treatment. This consumer only patronizes spas for having a good time and for using its collective and mainly water-related facilities: activity pools or water courses with pools at different temperatures, sauna and steam rooms. Thus, all the spa treatment rooms, costly to build and costly to equip, become unnecessary. Furthermore, labour costs are heavily trimmed as a consequence of reduced customer contacts.

The proposed concept is designed to question the three main features of the traditional spa business model: capital intensity; people intensity and quality control intensity. The low-cost spa concept is a back-tobasics strategy giving hospitality customers what they really expect from a spa experience and, thereby, reducing spa overhead and dramatically improving its results.

The shift to low-cost spas is likely to be considered as the next paradigm innovation in the spa industry, lowering prices and costs to open its services to larger markets. -The positioning statement seeks to develop collective areas such as activity pools, quite suitable for group use (family or friends), which provide great satisfaction to their users and allow for sharing a common enjoyable experience. This reduces a spa's customer contacts which lowers labour and training costs. This justifies a medium-low price strategy that fosters the scope of the market, allowing for the targeting of the peripheral consumer and the depicted positioning statement. -The targeting of the peripheral consumer is crucial for the success of the model. While a secondary segment for the spa industry, peripheral consumers are great in numbers and necessary clients to fill spas at vacation times. This spa user does not reserve individual treatments, hence spas save construction costs for treatment rooms and those incurred in furnishing rooms. This reinforces the medium-low pricing strategy and triggers the already stated consequences. -The medium-low pricing strategy has the positive effect of enlarging the target market to become an attractive offering even for peripheral consumers.

21. b) Low-luxury spa

The low-luxury spa (figure 8) is a variety of the low-spa concept. It is meant to cover the relaxation segment's needs. This consumer considers spas as places for relaxation and is the predominant client at most spas. Their sought after spa experience is that of a relaxation massage followed or preceded by a sort of relaxing bath. Standardization of the service and product bundling are key factors of success for this kind of spa in order to control costs while preserving quality perception. The choices bring about the consequences set forth herein.

-The positioning statement leads to developing collective areas such as water courses, and treatment rooms. This implies product bundling in order to tangibilize the offering to the target market. The tangibilization must incorporate the target segment's sought-after experience of a massage plus a water treatment. This requires a revenue management strategy to obtain the highest yield per available space and the highest productivity per employee; this supports a moderate pricing strategy requiring the standardization of the service providing to assure a cost control strategy that eventually favours the targeting of the relaxation segment and a positioning statement of escape and relax.

-The profile of the relaxation segment is the most common at spas worldwide (PKF, 2009; Stanford Research Institute, 2013). The satisfaction of its expectations activates the series of consequences already described. -The moderate pricing strategy implies the standardization of service as a way to reach the necessary cost control making the targeting of the relaxation segment with a positioning statement of escape and relax possible.

VI.

22. Conclusions

The research's objectives were the creation of theory to help in the explanation of how innovation occurs in the spa industry and how the kind of innovation present in the industry determines its evolution. The undertaken research yields the following results: 1. Preliminary innovation happens in clusters.

23. Spas with open innovation have always anticipated

and capitalized on changes in the environment. 3. Market-pull innovation rules the industry as a consequence of its multiple customer contacts.

24. Low-Luxury

| Source: own |

| i. Critical Product Innovations |

| Year | |

| 2 | |

| INNOVATIONS AIMED AT INCREASING DEMAND | |

| PRODUCT INNOVATIONS: | MARKETING INNOVATIONS: |

| TREATMENTS AND FITNESS (McNeil & Ragins, 2005) | THEME PACKAGES (Monteson & Singer, 1992) |

| CHOICE OF THERAPIST GENDER (McNeil & Ragins, 2005) BASIC PACKAGES (Monteson & Singer, 1992) | |

| LESSENING SPA MENU (Monteson & Singer, 2003) | SELLING OF BRANDED PRODUCTS (Reena, 2007) |

| SPA CLUSTER SUITES DEVELOPMENT (Reena, 2007) | PRESENCE IN THE RESORT (Monteson & Singer, 1992) |

| CONDO-SPA PARA "YOUNG OLDS" (Dwight, 1991) | POSITIONING (Monteson & Singer, 1992) |

| SPA COSMETICS BRAND (ISPA, 2009) | BRIDAL SHOWERS (Monteson & Singer, 1992) |

| LOW-COST MODEL (Rogers, 2008) | CREATE MANLY NAMES (McNeil & Ragins, 2005) |

| CROSS-SELLING STRATEGIES (McNeil & Ragins, 2005) | |

| FIRST-TIME WEB USERS(McNeil & Ragins, 2005) | |

| LIFESTYLE SEGMENTATION (Vyncke, 2002) | |

| INNOVATIONS AIMED AT REDUCING COSTS AND INCREASING PRODUCTION CAPACITY | |

| PROCESS INNOVATIONS: | ORGANIZATION INNOVATIONS: |

| IN-ROOM MASSAGES (Cavallari, 2008) | FLEXIBILITY AND VERSATILITY (Monteson & Singer, 1992) |

| EMPLOYEE CATEGORIZATION (Monteson & Singer, 1992) | |

| REVENUE MANAGEMENT (Kimes, 2009) | |

| LOWERING SPA LABOR COSTS (Monteson & Singer, 2003) | |

| Source: own | |

| e) Proposition 5 | |

| © 2014 Global Journals Inc. (US) | |

| 5. Easy | to | imitate | niche-creation | innovation | |

| characterizes the industry | Spa | ||||

| Bundling product | POSITIONING: Escape and relax | Collective facilities (a water course), and treatment rooms | |||

| Sought-after experience: Massage plus water treatment | TARGETING: Relaxation segment | Cost control | |||

| PRICING: | Standardization | ||||

| Revenue | Moderate | of service | |||

| management | |||||