1. Managing Bridging Capital in Post-Disaster Governance Networks in the United States and Indonesia

Liza Ireni-Saban Abstract-Purpose -This paper aims to explore the strategic use of bridging capital by brokers to facilitate coordination among civil society and state actor engaged in disaster response and relief efforts. Researching the dynamic of governance networks provides insights into the process of coordination and information and resource exchange to better utilize disaster management. Bridging capital used by brokers in disaster governance network allows mediating the flow of information among disconnected actors. The paper compares governance networks patterns and brokerage roles using evidence from the Gulf Coast Hurricanes (United States) and the West Sumatra Earthquakes (Indonesia).

Design/Methodology -The methodological approach used to explore brokerage roles is among interacting network members -ego-network. In an ego-network each actor is connected to every other actor in the network. However, there could be members of the network who are not connected directly to one another. Formalization of brokerage roles in a disaster setting assigns each actor in the network a numerical score that sums the different occasions of brokerage activity in which that specific actor is involved. The numerical score (brokerage score) is calculated by counting the number of times each actor plays the role specified in each brokerage category. Using techniques of social network analysis (SNA) can identify which organizations played brokers within governance networks during the phase of disaster response and relief efforts in United States (The Gulf Coast Hurricanes, 2005) and in Indonesia (the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami). The data was then analyzed by means of social network analysis using UCINET 6 software, as well qualitative analysis, from which the conclusions in this research are derived.

Findings -SNA analysis of the disaster governance network indicates greater effectiveness in terms of achieving coordination in the Indonesian case than in the US case. The findings of the research show that in the Indonesian case, the strategic use of domestic and international agencies as brokers is critical to build the bridging capital for successful coordination. In Indonesia response and relief efforts relied largely on local community capacities and partnerships with domestic public organizations, NGOs, and International agencies. Such partnerships were crucial not only for the effectiveness of the relief efforts but also to mobilize a relatively independent civil society. With the application of brokerage role analysis to the 2005 Katrina hurricane, U.S. state organizations were found to have relatively fewer ties in the network, with less potential to bridge other actors. A possible explanation of the differences between the U.S. and the Indonesian case based on network analysis and the findings from previous studies, could be that government committees such as the CBNO and civil society organizations had a builtin coordination structure that enabled them to frequently communicate with advocacy organizations that engaged in the recovery efforts. These committees became significant brokers on the basis of an expert authority that can be used by government to legitimize the subsequent regulatory outputs.

Research limitations -The present brokerage roles analysis suffers from several shortcomings. The data collected might be biased as most interactions are self-reported. In the case of both the Gulf Coast Hurricanes (United States) and the West Sumatra Earthquakes (Indonesia) recorded data collection was complex due to the fact that these countries had to face with massive damage which imposed constraints on access to state and local NGOs' resources and information. In addition, the data used in network analysis concerns ties among organizations rather than data on the attributes of each organization, such as data on members represented in these organizations, which could indicate the extent of an organization's fragmentation, and its functionality. In addition, in the case of Indonesia, recorded data collection was complex due to the different scale of disaster effects in different provinces in Indonesia. Such complexity was also exacerbated given the experience of thirty years of civil war in the region. In addition, the data used in network analysis concerns ties among organizations rather than data on the attributes of each organization such as data on members represented in these organizations, which could indicate the extent of an organization's fragmentation, which can undermine its functionality.

Practical Implications -The Gulf Coast Hurricanes (United States) and the West Sumatra Earthquakes (Indonesia) yielded insights into the importance of investment in bridging capital as a tool for managing the relationships between civil society and state organizations engaged in disaster response efforts to meet the demands of good governance. Based on the research findings, we propose enhancing collaborations between public officials and civil society organizations to build bridging capital in the disaster recovery by identify brokers that facilitate the flow of resources and information in the network that has already achieved credibility and reputation within communities at risk, strengthening the capacities of those possible brokers to avoid overload on formally designed brokering agencies and developing an entrepreneurial network in which a great number of entrepreneurs who fill the structural holes of the network can assist affected communities to articulate their needs in a way that enables the government to act on them. By drawing insights from governance networks studies we may be able to identify patterns of interactions between members in a network of embedded ties to increase successful disaster response management. The methodological approach used to assess the structural relationships among interacting members within the governance network and how those relationships yield varying effects is social network analysis (SNA). SNA is employed to assess how bridging capital is translated into a mediator within network governance to complement the scarcity of information and resources. More specifically, it is suggested that by using their capacity to make connections between collaboration opportunities, entrepreneurial brokers mobilize an effective, more accountable response system. (Mashaw 2006) For that, this paper applies the G&F brokerage roles framework to identify categories in which we might study the strategic use of brokers to facilitate an inclusive institutional structure that can enhance coordination among various members engaged in disaster relief efforts.

Using evidence from recent disaster events such as the Gulf Coast Hurricanes (United States) and the West Sumatra Earthquakes (Indonesia), it is argued that the comparison between these cases provides a setting by which we can further explore the strategic use of brokers to mobilize an effective response system in different governance networks. In this paper we focus on how institutional differences between the two countries, created by a diverse web of relationships between civil society and state organizations engaged in disaster response efforts may yield varying effects on disaster management performance. The American context represents old and mature civil society, while the Indonesian case represents young civil society, which until 1998 experienced dependence on an authoritarian regime. (Antlöv, Brinkerhoff, and Rapp 2010) This article is organized in three sections. The first section presents the relevance of governance network research regarding how bridging capital benefits coordination in disaster response and relief phase. The methodological section introduces social network analysis (SNA) to identify the structural relationships among interacting members and brokerage roles within the governance network and how those relationships yield varying effects. The third section presents empirical evidence from the selected case studies to assess the role of brokerage in increasing bridging capital for effective coordination in disaster relief efforts in the United States and Indonesia. This paper concludes with some practical implications for applying brokerage role analysis to underscore the value of state-civil society patterns of interactions to better target relief efforts and by extension, proactive disaster resilience building efforts.

2. II.

3. Bridging Capital and Governance Networks

Within the framework of social capital, structural characteristics of networks, i.e., an actor's position in a social network as determinant of its opportunity constraints is in relation to social capital associated with norms of reciprocity and trust. Thus, social network theorists have linked horizontal relationships with cooperative behaviors and norms of trust and reciprocity. (Thompson 2003) According to Thompson, trust is conceived as a fundamental norm of social networks; it is "established to precisely economize on transactions costs." (2003,32) Norms of trust and reciprocity are expected to increase the level of coordination by reducing uncertainty surrounding a partner's behavior and predict his future actions; "trust implies an expected action . . . which we cannot monitor in advance, or the circumstances associated with which we cannot directly control. It is a kind of device for coping with freedoms of others. It minimizes the temptation to indulge in purely opportunistic behavior." (2003,46) From a strategic point of view, the "bridging capital" of network actors is a form of intangible asset that is closely related to the bonds of connectedness formed across diverse actors engaged in a network that The question remains of how bridging capital translates into a mediator within governance networks to complement the scarcity of information and resources. Burt refers to the role of brokers by applying the notion of "structural holes" or "weak spots" in the overall structure or solidarity of the network. (Burt 2000) These holes or unconnected actors should be identified by an entrepreneur actor in a network to create a link between the two for possible collaborative opportunities. (Marsden 1982) Viewed in this way, when such structural holes identified as strategic positions are filled with brokers having bridging capital, the flow of information and resources becomes more efficient and effective. It should be noted that brokers do not necessarily presume to have their own resources and information, but rather they may have access to or control of the flow of resources and information among other actors, and they benefit from their embedded positions in a network.

The next stage is to examine the strategic use of brokers in the emergency response context; that is, how to make those brokers work for the shared goal of the emergency response system. Studies have long stressed the failure of coordination as a central factor in explaining poor performance during recovery phases in disaster management. ( identifies four main types of structural embededness in an emergency response network. Some actors are isolated from others, others take the dominant position in the network and serve as coordinators, some are more peripheral in that their interactions depend mostly on the coordination of brokering agencies, and other agencies take brokerage roles and strategically use their embeddedness in the network to achieve the shared goal of the network, using their reputational capital.

According to Burt (2000), during disaster events, governance networks tend to become less dense and thus likely to provide more strategic opportunities for entrepreneurial agencies. In this less dense network, actors may face severe problems of isolation that may challenge their access to critical information and resources, and only those actors endowed with bridging capital may play a critical role of connecting fragmented clusters. This paper addresses the typology of brokers in a network provided by Gould and Fernandez (1989). Gould and Fernandez categorized five types of brokerage roles: coordinator, consultant, gatekeeper, representative, and liaison. The coordinator is an agency that brokers a relation between two members of the same group; the consultant brokers a relation between two members of the same group, but is not itself a member of that group; the gatekeeper is a member of a subgroup who is at the boundary and controls access of external members to the group, the representative is a member of a subgroup that represents that group in connection with external partners, and liaison is a brokering agency that connects a relation between two groups, but is not part of either group. (Hanneman and Riddle 2005) The methodological approach used to explore brokerage roles is among interacting network members -ego-network. In ego-network each actor is connected to every other actor in the network. However, there could be members of the network who are not connected directly to one another, and if only ego has connections with other members of the network, ego may serve as a broker. As such; ego falls on the paths between the other actors in the network. (Hanneman and Riddle 2005) Operationalization of brokerage roles in a disaster context should take into account these categorization distinctions using techniques of social network analysis (SNA).

III.

4. Case Studies

The article uses case studies of disaster events that occurred in 2005 in the United States (Gulf Coast Hurricanes) and in 2004 in Indonesia (the West Sumatra Earthquakes). In Indonesia about 800 people were reported dead, with an estimate of more than 2,000 casualties. In addition, it was reported that hundreds of buildings had collapsed, which left thousands of people homeless. On August 29, 2005, the center of Hurricane Katrina passed east of New Orleans; winds downtown were in the Category 3 range with frequent intense gusts and tidal surges. At least 1,836 people lost their lives and eighty percent of New Orleans was flooded, with some parts under 15 feet (4.5 m) of water. The comparison between these cases provides insights into the governance networks involved in the policy domain of vulnerable communities' resilience efforts. the United States and Indonesia based on empirical data collected from 2005 to 2010, using a value matrix in which the intensity of the connections between the actors was valued between 0 (no relationship) and 3 (for a strong relationship). The data was then analyzed by means of social network analysis using UCINET 6 software, as well qualitative analysis, from which the conclusions in this research are derived. There were three phases in this study: 1. Data collection and mapping: the collected data for this study issued from content analysis of SITREPs (situation reports) that referred specifically to disaster response activities targeting vulnerable groups. Data on interactions between organizations was also collected from other sources such as news reports, governmental bills, proposals, statements, press releases, testimonies at government hearings, and websites of organizations engaged in disaster response using Lexis-Nexis program. The top 50 organizations from 2005-2010 were identified. The structured data from content analysis was used to map civil society and government organizations engaged in disaster response efforts. 2. The structured data from content analysis was used as an input to social network analysis (SNA). To run UCINET 6 software (Borgatti, Everett, and Freeman 2002), we produced a mode network (organization × organization matrix) using the coded interactions in which the intensity of the ties between members of the network was valued between 0 (no interaction) and 3 (for a strong interaction). A rating of 0 identifies that two actors have no regular contact or relationship; a rating of 1 indicates a level of weak relationship with low level of information exchange; a rating of 2 indicates more frequent interaction while all response efforts are made independently; a rating of 3 indicates strong ties with frequent interaction and reciprocity in information and resource exchange. (Marsden, P. V., and Campbell, K. E. 1984) Three network centrality measures were calculated as sources of advantage: degree, closeness, and betweenness. Degree measures the instant ties that an actor has, closeness measures the distance of an actor to all others in the network by focusing on the geodesic distances from each actor to all others, and betweenness measures the number of times an actor falls on the geodesic paths between other pairs of actors in the network, which indicates the extent to which such an actor can play the role of a broker. (Hanneman 2001) In addition, we used UCINET 6 software to compute and identify the number of brokerage roles played by different actors based on G & F brokerage roles typology .The frequency distribution of the number of brokerage roles that each ego node played during the response phase was created from ego network analysis and G & F Brokerage roles analysis.

V.

5. Findings and Discussion

6. a) United States

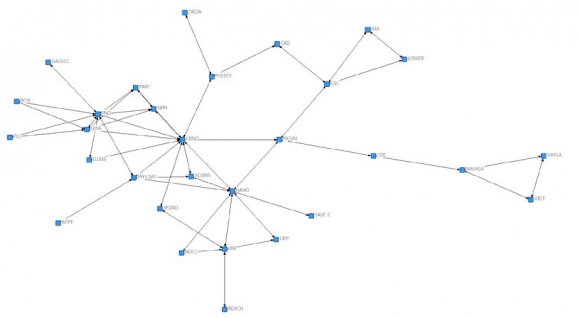

A visual representation of the overall network of organizations' interactions in community resilience efforts in the United States is presented in Figure 1. As indicated, the logic underlying measures of degree centrality is that actors who have more ties have greater opportunities, which makes them less dependent on any specific other actor, and hence more powerful. (Hanneman 2001) Table 1 presents the measures of degree of centrality. According to Table 1, CBNO has the highest level of degree centrality, followed by PNO (which means that other actors in the network seek to have ties to them, and this may indicate their importance). The Committee for a Better New Orleans (CBNO( was involved in the New Orleans Coalition on Open Governance (NOCOG), which consisted of six groups committed to promoting open, responsive, and accountable government and governance in New Orleans. NOCOG provides a broad-based, diverse representation of any organization in the city and a focus on change at systemic levels. 1 Within the NOCOG, CBNO engages in promoting the program of New Orleans Citizen Participation (CPP), which enables citizens to effectively participate in city government's priority-setting and decision making, and to provide an arena for open dialog between communities, neighborhoods, and city administration and government. This initiative is set to include the rights and needs of all communities for building a consensus-based decision-making structure that addresses the interests of the city as a whole. The mission of Puentes New Orleans, a non-profit community development organization, aimed to enhance community inclusion and participation in decision making. 2 In this case, the network centralization is 25.45, which leads to the conclusion that there is a lower amount of concentration or centralization in this whole network. A lower level of variability indicates that positional advantages are rather equally distributed in this network. However, degree centrality may take into account only the immediate ties of an actor. Thus, we need to add other measures such as closeness centrality to assess the structural advantage exerted by direct bargaining and exchange, such as the geodesic distances for each actor. Table 2 presents the measure of closeness centrality. We can see that CBNO, MQVN, and HANO are the closest or most central actors using this measure, because the sum of these actors' geodesic distances to other actors is the minimum possible sum of geodesic distances (the least farness). The post-Katrina recovery policies of the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) followed the "better and stronger" goal, and included wholesale destruction of still-viable public housing units in order to transform public housing residents' behavior. (NESRI. 2010) However, these "policies" were conceived as excluding black residents from articulating their special needs and concerns, making them powerless and unwelcome in their own communities. (Landphair 2007) Despite lack of material competencies, the Vietnamese community, united by the Mary Queen of Vietnam (MQVN) Catholic Church and Community Development Corporation, had already begun planning prior to the storm. The critical role played by the MQVN Catholic Church in community planning and recovery from Katrina fosters social cooperation and community rebound in the wake of disaster. (Weil 2011, 211-13) Pre-Katrina, MQVN's efforts were concentrated in Vietnamese-language religious services, Vietnameselanguage education, and occasional weekend markets for selling Vietnamese produce, arts, and crafts that allowed members to establish a distinguished ethnicreligious-language community.

In the wake of Katrina, MQVN's efforts included building a retirement home in a park-like setting, accompanied by an urban farm and farmers' market. The community even convinced FEMA to build a temporary trailer park on the site, laying all the plumbing and electrical work in such a way that it could then be transformed into the foundation of a retirement center. The coordinating competency of the church was reflected by the high degree of overlap between leadership within the church and formal secular civic activities including The Boards of Directors of the National Alliance of Vietnamese American Service Agency (NAVASA), Vietnamese Initiatives in Economic Training (VIET), the Community Development Corporation (CDC), and the Vietnamese-American Youth Leaders Association (VAYLA) (all housed at the church), which frequently overlap with each other and with the Pastoral Council. 4 Through these collaboration initiatives, the church provided space for after-school tutoring, English-language courses, Vietnameselanguage classes, youth leadership development, and business development. Another actor nearly as close, is Mayday, which engaged in the Campaign to Restore National Housing Rights, a coalition of housing rights groups from around the country that have united to force the U.S. federal government to recognize its obligation of adequate housing for all.

Table 2 also points to the ACRON and JFGNO organizations, which scored relatively high in closeness centrality but lower in other dimensions; thus they possess structural advantage exerted by direct bargaining and exchange, such as the geodesic distances for each actor rather than creating immediate ties with other actors in the network. The Jewish Federation of Greater New Orleans (JFGNO) engaged in extensive community recovery planning, building on a long-standing tradition of community competency. (Weil 2011) Due to its economic competency, the Jewish community was able to offer financial and communal incentives with event invitations to attract young people in both the business and the nonprofit realms. The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACRON) has acted on behalf of the low-income neighborhoods and families in New Orleans to raise their voice in decisions about rebuilding, and also instituted the ACORN Katrina Survivors Association, which became the first nationwide organization of displaced low-income New Orleans residents. 55 3 presents the measure of centrality betweenness, which provides a third aspect of a structurally advantaged position -the being between other actors. First we can see that there is a lot of variation in actor betweenness (from 0 to 414.533) and that there is a relatively high variation (std.dev.=103.035 relative to mean betweenness of 60.00). Despite this, the overall network centralization is high (45.17). In terms of structural constraints, there is high amount of "power" in this network, although we know based on the previous measures that one-fifth of all connections can be made in this network without the aid of any intermediary -which explains why there can be a lot of "betweenness". CBNO, MQVN and HANO appear to be relatively much more powerful than others, as indicated by this measure. Table 3 also shows that CSC and PNO scored the sixth and seventh highest, respectively, in their role as bridge among several organizations in the network. However, in its score of degree centrality, PNO is in a good position to gain information and resources from other actors in the network without the aid of an intermediary (relying on other organizations in reaching other actors in the network) rather than CSC (Table 1). Among efforts to advocate for addressing equity in recovery and rebuilding processes such as the Broadmoor Improvement Association and the Lower 9th Ward Neighborhood Empowerment Network Association, is the Churches Supporting Churches (CSC). The Churches Supporting Churches is a coalition of national and local churches aimed at increasing the engagement of community low income residents in policy advocacy by using participatory and formative evaluation and feeding back the results to the city recovery management officials and community members to incorporate the results into post-hurricane rebuilding programs. In order to corroborate these findings, we created an ego network of the top 30 organizations and calculated the number of brokerage roles played by them. From G & F brokerage role analysis, not even one organization served in a brokerage role. Thus, the G & F brokerage analysis results are compatible with the previous network analysis. It seems that if the recovery efforts for vulnerable communities were coordinated, G & F brokerage analysis would show a significant number of administrative or civil society organizations that took coordinator, liaison, and representative roles in connecting to other actors within the network. According to the ego network map and G&F brokerage roles analysis, we found that both state and civil society organizations did not take a leading role in a network to initiate or guide coordinated and collaborative efforts in response to vulnerable communities' resilience. (Kobila, Meek, and Zia 2010)

7. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

8. Indonesia

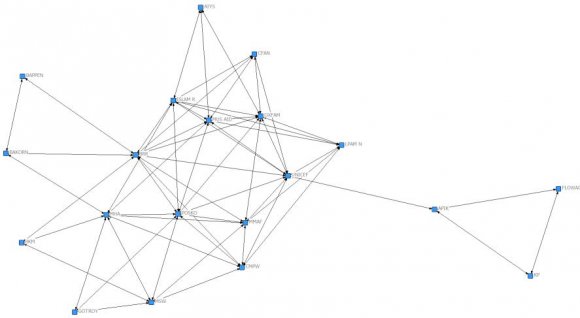

The map of the overall network of organizations' interactions in communities' resilience efforts in Indonesia is presented in Figure 2. Table 4 presents the measures of degree of centrality. According to Table 4, BRR has the highest level of degree centrality, followed by POSKO. On 13 January 2004, the village leaders established a posko (community command post) to represent the people in daily coordination meetings with aid workers. The posko entailed collection of accurate information on surviving families and needs, and coordinated the search and rescue (burials) along with coordinated emergency efforts and food distribution. During February 2005, schools were opened in tents. (Scheper 2006) The aftermath of the tsunami in Aceh province and Nias Island in Indonesia on December 26, 2004, destroyed hundreds of thousands of buildings leaving approximately 190,000 homeless, and 67,000 people including children living in barracks or tents. (BRR 2005) The 2004 disaster provided the government an opportunity to involve community stakeholders in postdisaster settlement and shelter decision making. Affected communities in Aceh became actively involved in the reconstruction process, putting pressures on the government by the Badan Rehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi (the institution in charge of coordinating Aceh's reconstruction) to use Western-modern style rather than timber dwellings as they symbolized a more developed and progressive image even at the cost of safety and security. (BRR 2006a(BRR , 2006b) Despite commitment to provide large compensation grants and support by international NGOs, Aceh suffered from a lack of professional or experienced construction staff, which did not match the international guidelines for transitional settlement and shelter to ensure sound technical advice for safer rebuilding. (UNHCR 2007) This problem was further intensified by the fact that many government offices were destroyed in the disaster, which resulted in poor coordination among organizations, and lack of coherent and consistent reconstruction policies.

In the Indonesian disaster setting, network centralization is 26.51, which leads to the conclusion that there is a lower amount of concentration or centralization in this whole network, similar to the level of centralization found in the U.S. case. A lower level of variability indicates that positional advantages are rather equally distributed in this network. Table 5 presents the measure of closeness centrality. The table shows that UNICEF, OXFAM, and MUS AID are the closest or most central actors using this measure, because the sum of these actors' geodesic distances to other actors is the minimum possible sum of geodesic distances (the least farness). International NGOs such UNICEF, OXFAM, and MUS AID were effectively coordinated with Indonesian domestic agencies. (Lassa 2012;Pandya 2006) Table 6 presents the measure of centrality betweenness. We can see that there is a lot of variation in actor betweenness (from zero to 100.363) and that there is a relative high variation (std.dev.=27.668 relative to mean betweenness of 21.200). The overall network centralization is low in comparison to the U.S. case (24.37). In terms of structural constraints, there a considerably low amount of "power" in this network, which denotes a low level of "betweenness". UNICEF, BRR, and APIK appear to be relatively much more powerful than others, as indicated by this measure. Table 6 also shows that ISLAM R and MUS AID are scored fifth and fourth while MMAF and OXFAM are scored the eighth and ninth highest, respectively, in their role as bridges among several organizations in the network. However, in its score of degree centrality, OXFAM is in a good position to gain information and resources from other actors in the network without the aid of an intermediary rather than MUS AID (Table 4). In order to corroborate these findings, we issued an ego network of the top 21 organizations and calculated the number of brokerage roles played by them. Table 7 presents the frequency distribution from ego network analysis and G & F Brokerage roles analysis. From G & F brokerage role analysis, major public agencies such as MHA, MMAF, and international organizations such as UNICEF, OXFAM, MUA AID, and ISLAM were major brokering agencies in this network. By following G & F typology of brokerage roles, MHA played brokerage roles most frequently. Especially during the recovery phase, MHA's brokerage roles were coordinator, gatekeeper, and representative. It created connections for active interactions with other domestic agencies and served as a major collaboration facilitator among domestic and international agencies to deal with vulnerable communities during the recovery phase. The consultant role played by the MMAF provides empirical evidence of the possible use of competent domestic agencies as brokers in disaster management systems. Similarly, UNICEF served as a significant broker for types of coordinator, gatekeeper, and representative roles; thus it maintained close collaboration with other international agencies. It is suggested that joint operations from international organizations needed to pass the gate of both public and international organizations. At the same time, collaborations from all different levels of jurisdictions in the public sector were played within MMAF, ISLAM R, and MUS AID (consultant role) where coordination among different groups of agencies were played by OXFAM (liaison role). As shown in Table 7, the major brokerage roles in this network were played by both domestic public (administrative) and international agencies. Thus, the G & F brokerage analysis results are compatible with the previous network analysis and the network map.

9. VI.

10. Summing up

By identifying the major structural features in network analysis we are able to address the barriers to building coordination among state and civil society organizations. SNA analysis of the disaster response phase network indicates greater effectiveness in terms of achieving coordination in the Indonesian case than in the United States case. The findings of the research show that in the Indonesian case, the strategic use of domestic and international agencies as brokers is critical to build the bridging capital of a successful coordination system to address the needs of affected communities. In Indonesia relief efforts relied largely on partnerships between civil society and state agencies. Such partnerships were crucial not only for the effectiveness of the relief efforts but also to mobilize a relatively independent civil society. Government, NGOs, and INGOs support for and further development of local communities' capacities in the disaster recovery process is essential for proactive resilience building an development of civil society based on Asian solidarity and cultural norms of mutual assistance. (Seybolt 2009) With the application of brokerage role analysis to the 2005 Katrina hurricane, state organizations were found to have relatively fewer ties in the network, with less potential to bridge other actors. Civil society organizations took the lead and allowed for open dialogue with effected communities to enable a shared understanding of needs and priorities in the face of adversity. (Ruscher 2006) However, this goes against the suggestion that civil society organizations have maintained consistent visibility to mobilize a relatively independent civil society in times of disaster. A possible explanation of the differences between the U.S. and the Indonesian case based on network analysis and the findings from previous studies, could be that government committees such as the CBNO and civil society organizations had a built-in coordination structure that enabled them to frequently communicate with advocacy organizations that engaged in disaster response efforts. (Yee 2004) These committees became an increasingly became significant brokers on the basis of an expert authority that can be used by government to legitimize the subsequent regulatory outputs.

11. VII.

12. Conclusion

Natural disasters impose constraints in enhancing coordination more than in "good times". In terms of the bridging capital (BC) framework introduced in this paper, state and civil society organizations must manage their bridging capital strategically in response and relief efforts to reduce disaster vulnerabilities.

The Gulf Coast Hurricanes (United States) and the West Sumatra Earthquakes (Indonesia) yielded insights into the importance of investment in bridging capital as a basis for good governance. In the case of Katrina in 2005, civil society organizations and groups developed joint projects and networking with government actors by encouraging marginalized communities to participate in disaster recovery and assessment of risks. Collaborations with government actors relied heavily on civil initiatives rather than on state initiatives. Thus, civil society organizations' performance in the wake of Katrina symbolizes a proactive stance in building a cooperative sphere within civil society organizations and with state agencies, although they did not take brokerage roles to share their valuable resource with state agencies in the network to pursue collective goals. In the case of the West Sumatra Earthquakes, admirable spontaneous and voluntary cooperation in the disaster-affected areas in Indonesia were facilitated by coordination between government and civil society underlying the long tradition of solidarity and cultural norms of mutual assistance. State and civil partnership were especially essential in empowering post-tsunami vulnerable groups such as women, children, refugees, and the elderly. These partnerships are also crucial in terms of bridging capital, in the broader social, political, and economic context by opening up possibilities of providing an associational sphere, which enables reduction of the long-term government suspicion of NGOs. (Brass 2012;Reimann 2006) Both domestic and international organizations filled the structural holes of the network to maintain the capacities and involvement in the government disaster management system of communities at risk. Thus, by studying the role of brokers in times of disaster, scholars may better address the way bridging capital impacts the quality of democratic anchorage in the long run.

Based on the research findings, we propose to build bridging capital in disaster management through the strategic use of brokers by identify brokers that facilitate the flow of resources and information in the network that has already achieved credibility and reputation within communities at risk; strengthen the capacities of those possible brokers to avoid overload on formally designed brokering agencies and develop an entrepreneurial network in which a great number of entrepreneurs who fill the structural holes of the network can assist affected communities to articulate their needs in a way that enables the government to act on them.

13. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

Volume XIV Issue VII Version I Year ( )

A

| Year |

| Volume XIV Issue VII Version I |

| ( ) |

| Global Journal of Management and Business Research |

| SSQ=Sum of Squares; MCSSQ=Mean Centered Sum of Squares; EucNorm |

| =Euclidean Norm |

| Betweenness | nBetweenness | |

| Mean | 60.000 | 7.389 |

| Std Dev | 103.035 | 12.689 |

| Sum | 1800.000 | 221.675 |

| Variance | 10616.162 | 161.011 |

| SSQ | 426484.844 | 6468.321 |

| MCSSQ | 318484.844 | 4830.329 |

| Euc Norm | 653.058 | 80.426 |

| Minimum | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Maximum | 414.533 | 51.051 |

| Degree | NrmDegree | Share | |

| Mean | 13.400 | 23.509 | 0.050 |

| Std Dev | 6.240 | 10.948 | 0.023 |

| Sum | 268.000 | 470.175 | 1.000 |

| Variance | 38.940 | 119.852 | 0.001 |

| SSQ | 4370.000 | 13450.292 | 0.061 |

| MCSSQ | 778.800 | 2397.045 | 0.011 |

| Euc Norm | 66.106 | 115.975 | 0.247 |

| Minimum | 6.000 | 10.526 | 0.022 |

| Maximum | 27.000 | 47.368 | 0.101 |

| Network | |||

| Centralization=26.51% | |||

| Heterogeneity=6.08% | |||

| Normalized=1.14% | |||

| Degree | NrmDegree | Share | |

| BRR | 27.000 | 47.368 | 0.101 |

| POSKO | 23.000 | 40.651 | 0.086 |

| UNICEF | 19.000 | 33.333 | 0.071 |

| OXFAM | 18.000 | 31.579 | 0.067 |

| MUS AID | 18.000 | 31.579 | 0.067 |

| MAH | 18.000 | 31.579 | 0.067 |

| ISLAM R | 18.000 | 31.579 | 0.067 |

| CMPW | 17.000 | 29.825 | 0.063 |

| LPAM N | 16.000 | 28.070 | 0.060 |

| Notes: SSQ=Sum of Squares; MCSSQ=Mean Centered Sum of Squares; EucNorm=Euclidean Norm | |||

| inFarness | inCloseness | |

| Mean | 40.200 | 40.200 |

| Std Dev | 8.936 | 10.303 |

| Sum | 804.000 | 804.000 |

| Variance | 79.860 | 106.160 |

| SSQ | 33918.000 | 34444.000 |

| MCSSQ | 1597.200 | 2123.200 |

| Euc Norm | 184.168 | 185.591 |

| Minimum | 28.000 | 29.000 |

| Betweenness | nBetweenness | |

| Mean | 21.200 | 6.199 |

| Std Dev | 27.668 | 8.090 |

| Sum | 424.000 | 123.977 |

| Variance | 765.532 | 65.450 |

| SSQ | 24299.438 | 2077.514 |

| MCSSQ | 15310.638 | 1309.004 |

| Euc Norm | 155.883 | 45.580 |

| Minimum | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Maximum | 100.363 | 29.346 |

| Network | ||

| Centralization=24.37% | ||

| Betweenness | nBetweenness | |

| UNICEF | 100.363 | 29.346 |

| BRR | 71.903 | 21.024 |

| APIK | 68.000 | 19.883 |

| MHA | 35.307 | 10.324 |

| ISLAM R | 26.678 | 7.801 |

| MUS AID | 26.351 | 7.801 |

| POSKO | 20.380 | 7.705 |

| MMAF | 17.720 | 5.959 |

| OXFAM | 16.526 | 5.181 |

| SSQ=Sum of Squares; MCSSQ=Mean Centered Sum of Squares; Euc | ||

| Norm=Euclidean Norm | ||

| Name | Coordinator Gatekeeper Representative Consultant Liaison Total | |||||

| MHA | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| UNICEF | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| ISLAM R | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| MUS AID | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| MMAF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |