1. Introduction

ost-conflict or in conflict countries, such as Iraq, are characterized by damaged economies and fragile states' institutions that require rebuilding as a precondition for sustainable economic development (The World Bank, 2011). Foreign direct investment has become a valuable tool to rejuvenate industries, rebuild infrastructures, and eventually aid in the process of peace building (Turner, Aginam & Popovski, 2008). However, international business transactions involve interactions by individuals with different cultural value systems. Multinational enterprises (MNEs) operating in different countries face the burden of adapting to local culture manifested by the nation's political economy, people's customs, language, education, and religion (Tihanyi, Griffith & Russell, 2005). The difference between MNEs' home culture and that of their host countries of operation, that is, cultural distance, has been addressed extensively by current literature (Drogendijk & Slangen, 2006;Fiberg & Loven, 2007;McSweeney, 2002;Rozkwitalska, 2013;Tihanyi et al., 2005). The underlying concept of cultural distance is the effect on business relationships and management of MNEs by the behavior of people of different cultures. Cultural distance has been used as an explanatory variable in the entry mode choices made by MNEs in a foreign country (Fiberg & Loven, 2007).

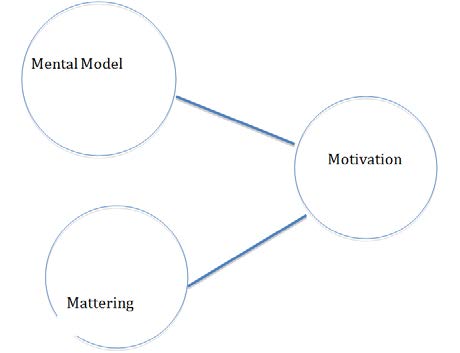

According to Dunning's eclectic paradigm, a firm's ownership and internalization advantages, in addition to locational advantages, are important determinants of foreign direct investment (FDI) choice of entry mode (Dunning 2001). Existing literature on the role of location specific factors impacting FDI entry strategies (see Figure 1) included host country political and security risks, market size, human capital, technological gab, cultural distance, state and economic institutions, corruption, natural resources, openness of economy, and banking system ( Post conflict countries, such as Iraq, and due to their political instability tend to attract smaller amounts of FDI than those with more stable state and economic structures. In contrast to political and security risks, culture is interacted in market actions and conditions in a given country through people's beliefs, traditions, customs, practices, and value system (Keillor, Hauser & Griffin, 2009). Hofstede (1983, p. 76) defined culture as ".. its essence is collective mental programming; it is that part of our conditioning that we share with other members of our nation, region, or group but not with members of other nations, regions, or groups".

Large cultural distance limits a firm's ability to exploit its ownership advantages in foreign markets. Competing against local companies would be difficult as is the case in managing local employees, customers, suppliers and relationships with government officials. Acquiring local business will allow the foreign firm to understand the host country's environment as well as establish the necessary local business networks (Hu et al., 2012). In host countries where MNEs have strong technological advantages and international presence, greenfield and joint-venture investments are utilized. MNEs have also relied on the skills and knowledge of host country expatriates to manage operations in their countries of origin, although the number of those expatriates is small compared to home country expatriates (Joshi & Ghosal, 2009). MNEs send their own home country employees to manage their foreign operations in accordance with their home country culture (Patrick, Felicitas & Albaum, 2005). Those home nationals, while lacking good understanding of local culture, tend to have a better understanding and greater commitment to MNEs corporate goals than those hired locally (O'Donnell 2000). Due to MNEs preferring their own home country expatriates to run their operations abroad, the role of host country expatriates in narrowing the cultural distance between that of their employers and their countries of origin seems to be contingent on availability of opportunities provided to them by their employers.

Cultural distance, as used by current literature, refers to differences between cultures of national groups; each having their own characteristics of shared single dominant language, political system, educational system, army, as well as shared mass media, market, and national symbols (Schwartz, 1999). In heterogeneous countries with distinctive cultural groups (i.e. minorities), such as Iraq, the description of national culture referred to that of the dominant majority group, and in case of Iraq, that of its Arab majority. Kurds, as the dominant ethnic group in the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region of Iraq have a distinct culture compared to that of Iraqi Arabs, who dominate other parts of the country.

As a post conflict country with ongoing low scale insurgency, Iraq suffers from violent activities of terrorists groups that target civilian population as well as economic targets. The semi-autonomous Kurdistan region has enjoyed a relative security compared to other parts of Iraq. Investment activities in Kurdistan region have been more active compared to other parts of Iraq (Hanna, Hammoud & Russo-Converso, 2014).

This study addressed a need in current literature, that of the impact of host country distinctive cultures in heterogeneous and post-conflict countries, such as Iraq, on foreign direct investment and its mode of market entry. The research questions that were addressed are: 1. What is the impact of cultural distance on foreign direct investment activities in the post-conflict country of Iraq? 2. How does cultural distance affect MNEs choice of market entry mode in Iraq? 3. What is the role of regional differences in influencing MNEs decisions to invest in Arab and Kurdish parts of Iraq?

The first research question will address impact of cultural distance in influencing MNEs decisions to invest in the post-conflict country of Iraq. The second question will address the choice of mode of market entry (e.g. greenfield investment, joint ventures or Merger and Acquisitions) foreign direct investments take in Iraq. The third question will address the role of regional differences in influencing MNEs decisions to invest in a particular region of the host country.

2. II.

3. Research Method

This study utilized a qualitative research method and explorative case study design to answer the research questions. Qualitative research examines a setting or a phenomenon from the perspective of deep understanding rather than micro-analysis of limited variables, as the case is with quantitative research. Instead of trying to prove or disprove a hypothesis, qualitative research seeks themes, theories, and general patterns to emerge from the data. Qualitative research is "hypothesis generating" (Merriam, 1988, p. 3) rather than hypothesis testing as is the case with quantitative research.

Despite the limitations of a single-country study, each case produces a more detailed picture and provides practical policy inferences. Single case study could be used as a comparative method when using "concepts that are applicable to other countries to make larger inferences beyond the original country used in the study" (Landman, 2008, p. 28). Case study was chosen due to the need for an in-depth understanding of cultural distance, as a locational factor, and the challenges facing FDI in a heterogeneous and post-conflict country, such as Iraq. The primary data for the case study were collected through one-on-one interviews with subject matter experts (SMEs) while secondary data were collected through conducting a review of publically available documents (e.g. reports by government agencies and private organizations). As with all data, analysis and interpretations were required to bring order and understanding.

Determining sample size in qualitative studies is based on the concept of saturation when the collection of new data does not shed any further light on the issue under investigation (Sandelowski, 1995). To ensure most or all important perceptions are covered, qualitative samples must be large enough but not too large to cause data to be repetitive, and eventually redundant (Mason, 2010). In purposeful sampling, a small sample that has been systematically selected for typicality and relative homogeneity provides far more confidence that the conclusions adequately represent the average members of the population than does a sample of the size that incorporates substantial random or accidental variation (Maxwell, 1998). Based on the research topic, a sample size of 15 SMEs was sufficient to satisfy the concept of data saturation and to meet the research purpose. The participants were Iraqi government officials, employees of MNEs investing in Iraq, and members of the academia or professionals familiar with the topic. The selection of SMEs was based on the demonstrated knowledge by the selectee of foreign direct investment and Iraq reflected either by job position or publications that confirm knowledge in the subject area. Employees of MNEs were chosen for their professional knowledge in the subject rather than as representatives of their respective employers. The interviewees were solicited to explain SMEs' views on what they consider to be the factors impacting FDI in Iraq, specifically cultural distance, and why they believe so. A semi-structured and an in-depth interviewing format were utilized for the collection of data.

Interviewing was performed in Iraq. English was the main language of interviewing, however, in interviewing Iraqi officials, Arabic language was used when appropriate. The researchers were well versed in both Arabic and English with native-level proficiency in both languages, and were well aware of cultural sensitivities and practices. Most Iraqi officials

4. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

Volume XIV Issue IV Version I Year ( ) interviewed were English-speaking individuals, having been educated in English-speaking western nations.

Data processing consisted of carrying out activities such as checking the completeness and quality of collected data, checking the relationships between data items (e.g., interviews, field notes, reports), and preservation of source confidentiality and anonymity. Data were then converted into electronic text format suitable for both preservation and dissemination. Data analysis included a description of sample population, coding of collected data, displaying of data summaries to facilitate interpretations, drawing conclusions, and finally developing strategies for confirmation of the findings.

5. III.

6. Research Results

All the 15 participants (SMEs) lived and/or worked in Iraq, where the interviewing took place. Table 1 is a display of interview participants' qualifications. Pseudonyms A1 thru A15 were assigned in order to protect confidentiality of the participants; it was the responsibility of the researchers to ensure no data were linked back to anyone individual. Nine (or 60%) out of the 15 participants agreed with the concept that Kurdish political and group culture is more open to FDI than that of Iraqi Arabs. Also, an overwhelming responses of participants 13 (or 87%) out of the 15 thought foreign firms faced less obstacles in conducting their business in Kurdistan compared to other parts of Iraq. Participants attributed that to policies and commitment of Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) to attracting FDI to the region. For the same period of 2011-2013 the total value of investment licenses issued by KBI also showed a steady increase and amounted to $3.2 billion in 2011, $5.8 billion in 2012 and $12.4 billion in year 2013. In contrast KBI more than doubled the number of licenses issued in 2013 compared to those issued in 2007. In 2011, there were 80 licenses issued totaling in value $3.2 billion, while those in 2013 were 129 licenses totaling $12.4 billion. While the total value of investment more than quadrupled in 2013 compared to 2011, this increase in investment value in Kurdistan was attributed to two major investments, one by UAE investors and the other by a joint Iraq/Iran venture. The two licenses were worth a total of $4.4 billion.

The data in Tables 3 and 4 show investments by foreign entities including those of limited number of Western and Asian firms (refer to Table 6 for a breakdown by foreign nationality). While one could argue that political instability in Iraq was the reason for the reluctance of Western firms to invest, the relative stability of Kurdistan region gives more credence to factors such as cultural distance. Further, most of the foreign investments reported in Tables 3 and 4 were in Iraq's real estate sector rather than in its industrial. Table 5 shows the value of licenses issued by NIC and KBI to foreign investors interested in wholly-owned real estate construction projects. The percentage of foreign investment in the housing sector that were issued by NIC were 82.6%, 94.2% and 96.4% of total value of licenses issued to foreign investors for the years 2011, 2012, and 2013 respectively. While those issued by KBI were 94.6%, 81%, and 99.3% for years 2011, 2012, and 2013 respectively.

7. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

Volume XIV Issue IV Version I Year ( ) Investment in a real estate construction projects does not qualify as FDI since it is an investment made for quick profit, and where investors' relationship with the project comes to an end as soon as construction is completed and the housing project is sold to prospective buyers. Such projects hold no long-term interests by the foreign investors as is required for projects to qualify as FDI. It should also be noted that data shown in Tables 3 and 4 excluded investment licenses issued for firms investing in Iraq's oil and gas sectors. Both the NIC and KBI charters exclude them from issuing such licenses. Currently, and until the time the Hydrocarbon law is approved by Iraqi parliament, all work with foreign oil companies is conducted by Iraq's Ministry of Oil and Kurdistan Regional Government.

Table 6 shows the nationality of foreign firms that were issued investment licenses by Iraqi NIC and KBI. The findings showed most of foreign investors in Iraq were Arabs, Turks, and Iranians indicating a closer proximity to Iraq's culture. This confirms that cultural distance as locational factor attracts investors when the cultural difference is small. The data showed limited number of investors from countries with a large cultural distance with that of Iraqis, Arabs, or Kurds. The number of licenses (greenfield projects) issued for Western and Asian firms investing in Iraq (including Kurdistan), as shown in Table 6, and for Year 2011 were a total of 13 licenses (29.5% of total foreign issued) compared to 31 for Arabs, Turks, and Iranians, while for Year 2012 there were 14 licenses (34% of total foreign issued) and 27 respectively. For Year 2013, there were 5 licenses (15.6% of total foreign issued) issued to western firms compared to 27 for Arab, Turkish, Iranian and Asian firms. It should be noted that not all licenses issued to foreign investors were actually "foreign".

While data in Table 6 shows a combined total of eight licenses issued by NIC and KBI during 2011-2013 for investors from the United States, it's the opinion of the authors that four of them were actually issued to Iraqi expatriates rather than US nationals. The other four licenses issued under USA were two for 2011 worth $59.6 million that was not acted upon and cancelled (see Table 7) and another worth $300,000 (both issued by NIC). The other two for 2012, were the same $300,000 license reported again (hence, should be discarded) and a Hilton Hotel worth $14.8 million (issued by KBI). Same could be said about investors from Germany. The two licenses issued in 2011 and 2012 by KBI were for Iraqi expatriates (of Kurdish ethnicity). Only the license issued by NIC in 2011 and worth $223 million could be attributed to a true German firm. It should also be noted that the total value of licenses issued by NIC for Asian firms (Korean, Chinese and Indian) for Year 2012 were worth $9.198 billion (mainly due to Korean planned investment of $7.75 billion) and for Year 2011 was worth $303.3 million (Korean and Chinese). In 2013, NIC issued an investment license worth $450 million to an Indian firm, while those issued to Slovenian, British, Dutch, and Brazilian were worth a total of $433 million. Kurdistan Board of Investment issued in 2013 one license to an American investor (an Iraqi expatriate) worth $2.5 million.

Slovenia (1), UAE

, Britain (1), Iran (1), Brazil (1), India (1), Holland

Turkey ( 5), USA (2), Germany (1), Lebanon (1),

Turkey (3), USA (2), Germany (1), Lebanon (2), UAE(1) Russia (1), Iran (1), Georgia (1)Turkey (3), USA (1), Lebanon (1), Iran

Note. *Data from unpublished reports (in Arabic) by NIC; "NIC Achievements for Year 2011", "NIC Achievements for Year 2012", "NIC Achievements for Year 2013" and by Kurdistan Board of Investment (2014). It should be noted that issuing licenses is no guarantee of start of work and many of those issued by NIC ended up not being acted upon due to problems faced by investors. Actually, according to NIC unpublished report of "NIC Achievements in Year 2013" (in Arabic) that was provided to researchers, the total value of licenses facing problems and on hold was $26.8 billion or 98.8% of the total issued of $27.3 billion. For Year 2012, those on hold were worth $6.9 billion or 39.48% of total issued of $17.6 billion. This is a substantial number of investment licenses not acted upon due to hurdles brought about by government agencies. Table 7 shows three licenses issued by NIC in 2011 totaling over $213 million that were investigated by researchers and shown as not acted upon by foreign investors due to hurdles created by Ministry of Electricity that was resisting at the time, any role by private investors in the electricity sector. ** barrels per day (bpd).

Table 8 shows wholly owned firms by MNE with major equity owned by Iraqi expatriates. Mass Global, the owner of all three privately-owned power plants in Kurdistan has its capital funded by a group of Iraqi and foreign investors. Same could be said about the KAR Group the owner of an oil refinery in Erbil and a holder of a major profit sharing contract (PSC) oil contract in Kirkuk area. The two Iraqi expatriates (of Kurdish ethnicity) own four out of the six wholly-owned projects in Iraq. The findings of this study showed no investment licenses issued by NIC to local Iraqi Arabs allowing them to invest in power plants or refineries, and whether such applications were made was not clear.

While investigation of the role of expatriates was not an intended research question to answer, however, the findings of this study showed it as an important feature of FDI investment in Iraq. The findings agree with existing literature (Dobrai, Farkas, Karoliny & Poor, 2012; Wang, Tong, Chen, Kim & Hyondong, 2009). In the case of Iraq, at least, expatriate nationals were more willing to waive the political risks and uncertainties in their country of birth and invest there. Their extensive knowledge of their original country (culture, language, how the system works, etc.) have provided them with the necessary tools to make the right business contacts, work, and navigate easily within the system. Personal contacts play important role in business transactions around the world, and in a developing society like Iraq, where communal rather than individualistic culture dominates,

8. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

Volume XIV Issue IV Version I Year ( ) those contacts play a more critical role in facilitating those business transactions and resolving problems along the way. Table 9 shows the nationality of joint ventures for years 2011-2013. Three investments were made by Iraqi expatriates in joint ventures with their co-nationals. While NIC data reported the joint ventures by citizenship of the investors, it's also possible that certain reporting indicated as "foreign" might also refer to an Iraqi expatriate investing in his/her country of origin. The same could be said about reporting by Kurdistan Board of Investment.

It's noteworthy from results of Table 9 that cultural distance is small or non-existent in the case of joint venture licenses issued by NIC in 2011-2013, while those issued by KBI showed several foreign firms willing to partner with Kurdish investors. These findings confirmed earlier results of those of green field investments shown in Table 6. The data also shows the limited if almost non-existence of any joint venture projects with nationals of Western nations. This fact strongly points to the cultural estrangement that characterizes investment activities by Western firms in Middle Eastern countries, such as Iraq.

IV.

9. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of cultural distance on foreign direct investment and its mode of entry that foreign investors choose to make in the post conflict country of Iraq. While parts of Iraq are scene for active insurgency, Kurdistan region has been relatively more secure. Most of the foreign investors were from Arab countries that share same culture and language of that of dominant group in Iraq, as well as from Iraq's neighbors. The findings of this study showed foreign investors interested in Iraq included small number of Western firms' demonstrating that cultural distance play an important role in investment decisions by MNEs. Limited number of joint venture licenses was issued by both Iraqi NIC and KBI. Some of those wholly-owned and joint ventures were between Iraqi expatriates and their local partners in their country of origin.

Concerns with political instability and security continue to be the driving forces behind types of investment Iraq is attracting. The findings of this case study showed investments (excluding that in natural resources) by western MNEs in the post-conflict country of Iraq, were limited if not totally insignificant to its economic reconstruction. Despite their seeking shortterm engagements, such as those in the housing sector, Asian firms showed greater propensity to accepting higher risks and willingness to invest in Iraq, unlike their western counter parts that were mainly interested in Iraq's oil and gas sector and showed no inclination to invest in other sectors of Iraq's economy. The findings of this study suggest that post-conflict countries should direct their efforts (at least until stabilization of their economic, institutional and regulatory conditions was achieved) to attracting FDI from neighboring countries or those of smaller cultural distance.

Substantial number of licenses issued by NIC ended up being cancelled or put on hold indefinitely due to hurdles caused by government agencies. Statistical data provided by NIC (pre-2012) do not account for such inactive or cancelled licenses. While total dollar amount of licenses issued by both NIC and KBI show continuous attraction of foreign investors to the Iraqi market, data about the final number of licenses that were acted upon along with the final dollar figure of actual foreign investment in Iraq is still lacking.

Most of foreign investments in Iraq did not qualify as foreign direct investment due to inclinations by investors to engage in quick turn-around projects that yield fast profits and limit their exposure to long term risks. Concerns with political instability and security are driving forces behind types of investment the post conflict country of Iraq is attracting. It also reflects the view that foreign investors lack confidence in Iraq's industrial sector and its pool of skilled labor or lack of. Iraq lost thousands of engineers and skilled labor who left the country due to the continuous internal strives. This in turn adds credence to the role the state has to continue to play in the economic development of post conflict countries. Unless major steps are taken by Iraq to divert substantial amounts of its oil proceeds into the industrial sector, Iraq and other post conflict countries with abundance of oil (or other natural resources) will continue to depend in the foreseeable future on goods manufactured by more advanced countries. Their economies will continue to be, in large part, a consumer of industrial products from developed economies and will continue to lag behind technological development.

The phenomenon of expatriates playing the role of advocates for FDI should be encouraged by all governments of post conflict countries. The role played by Iraqi expatriates in influencing their employers' decision to invest in their country of origin highlighted a variable of the ownership advantages that has not been addressed adequately by scholars investigating the OLI paradigm. The case of Kurdistan showed that in order to harness the technical expertise and financial power of expatriates, it is important to create the necessary conditions to encourage their return. Expatriates could bring a much needed talent that could help in the economic reconstruction and development of post conflict countries. Creating a peaceful environment, clear commitment to economic development and transparent policies that address corruption, as well as providing a legal framework that could adequately resolve disputes are but few of those policies that would go long ways to meet the needs of returning expatriates.

Since this qualitative method defined and explained the constructs under exploration, a quantitative method could be utilized in the future to test the relationship between cultural distance, as a distinctive locational factor, and FDI inflows as well as its relationship with MNEs choice of mode of entry. It's recommended that this type of quantitative research be developed to further examine the effects of cultural distance on performance of FDI in Iraq.

10. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

Volume XIV Issue IV Version I Year ( )

| Participant Pseudonym | Qualifications | ||

| A1 | Member of Iraqi Parliament | ||

| (chairman | of | relevant | |

| parliamentary committee) | |||

| A2 | Member of Iraqi Parliament | ||

| A3, A4 | Member of Advisory Commission - | ||

| Iraqi Prime Minister's Office | |||

| A5, A6, A7 | Employee (A5 a manager) of Iraq | ||

| National Investment Commission | |||

| -Council of Ministers | |||

| A8 | Manager, Iraq's Ministry of Oil | ||

| A9 | Manager, Iraq's Ministry of | ||

| Electricity | |||

| A10 | Manager, Economic | Section, | |

| Iraq's Council of Ministers | |||

| A11*,A12*, A13* | Managers (A13 was Vice Pres- | ||

| ident) at foreign oil companies | |||

| investing in Iraq | |||

| A14 | Manager, Board of Investment - | ||

| Kurdistan Regional Government | |||

| (KRG) -Iraq | |||

| A15* | Consultant, employee of a | ||

| German firm providing advice on | |||

| investment policy to Board of | |||

| Investment, KRG -Iraq | |||

| Note. *Participant's firm will not be declared, since the | |||

| individual participated as a SME rather than | |||

| representative of his company. | |||

| Factor Name | Number of | Number of | ||

| participants | Participants | |||

| agreeing | disagreeing | |||

| Political stability was the | 9 | 6 | ||

| reason for larger FDI | ||||

| inflows in Kurdistan | ||||

| compared to other parts | ||||

| of Iraq | ||||

| Kurdish political and | 9 | 6 | ||

| group culture more | ||||

| open to FDI than Iraqi | ||||

| Arab | ||||

| Kurdistan | Regional | 13 | 2 | |

| Govern-ment policies | ||||

| are more committed to | ||||

| FDI | than | federal | ||

| government | ||||

| Investors' Nationality | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

| Foreign | 735 | 273 | 129 | 1,069 | 288 | 602 | 2,444 |

| Joint Venture | 457 | 148 | 13 | 129 | 278 | 20 | 2,750 |

| National | 2,773 | 1,605 | 4,022 | 3,686 | 2,637 | 5,240 | 7,225 |

| Total value | 3,966 | 2,026 | 4,164 | 4,883 | 3,204 | 5,863 | 12,419 |

| Number of lice-nses issued | 51 | 63 | 76 | 107 | 80 | 136 | 129 |

| Note. * |

| Investors' Nationality | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Foreign | 3,443 | 10,129 | 22,074 | |

| Joint Venture | 295 | 292 | 166 | |

| National | 7,365 | 7,208 | 5,075 | |

| Total value | 11,103 | 17,630 | 27,315 | |

| Number | of | |||

| licenses issu- | 300 | 238 | 159 | |

| ed | ||||

| Note. *Data from unpublished reports (in Arabic) by | ||||

| NIC; "NIC Achievements for Year 2011", "NIC | ||||

| Achievements for Year 2012", "NIC Achievements for | ||||

| Year 2013". | ||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

| Amount in | Total | Amount in | Total | Amount in | Total | |

| Housing | Foreign | Housing | Foreign | Housing | Foreign | |

| Invested | Invested | Invested | ||||

| Kurdistan | 233 | 246 | 528 | 651 | 2,824 | 2,843 |

| Region | ||||||

| Iraq | 2,910 | 3,520 | 9,386 | 9,963 | 21,285 | 22,074 |

| (excluding | ||||||

| Kurdistan) | ||||||

| Note. *Data from unpublished reports (in Arabic) by NIC; "NIC Achievements for Year 2011", "NIC | ||||||

| Achievements for Year 2012", "NIC Achievements for Year 2013" and by Kurdistan Board of | ||||||

| Investment (2014). | ||||||

| Iraq (excluding Kurdistan) | Kurdistan | ||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

| Turkey (16), USA | South Korea (1), | ||||

| (3), Germany (1), | Canada (1), China | ||||

| Lebanon (2), UAE | (2), Iran (2), India | ||||

| (5), China (1), | (1), USA (3), | ||||

| Kuwait (2), Italy | Lebanon (3) | ||||

| (1), Denmark (1) | Turkey (3), Kuwait | ||||

| Romania (1), | (2), | ||||

| Spain (1), Korea | UAE (6), Finland | ||||

| (1), Britain (1) | |||||

| Project | Investing | Nationality of | Amount of | Province | |

| company | Investor | Investment | |||

| Providing 150 MW of | Dao al-Jameeh | United Arab | $125.5 | Basra | |

| electricity | Company | Emirates | |||

| Providing 50 MW of | US | Industrial | USA | $59.6 | Basra |

| electricity | Services | ||||

| Building power station Rotam Group | Turkish | $28.2 | Najaf | ||

| Note. | |||||

| Kurdistan Region*. | ||

| Name of firm with | Plant | Total |

| equity owned by | Capacity | |

| expatriate | ||

| Mass Group Holding | Three power pla- | 2.0 GW |

| nts | ||

| KAR Group | One oil refinery | 80,000 bpd* |

| Iraq (excluding Kurdistan) | Kurdistan Region | ||||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

| Iraqi/Greek (Iraqi | Iraqi/Turkish | Iraqi/British | Iraqi/Turkish | Iraqi/Dutch | Iraqi/German |

| expatriate) | Iraqi/Lebanese | ||||

| Iraqi/Lebanese | Iraqi/Lebanese | Iraqi/Spanish | Iraqi/Pakistani | Iraqi/Turkish | |

| Iraqi/Turkish | Iraqi/Austria (Iraqi | Iraqi/Jordanian | Iraqi/Turkish | Iraqi/UAE | |

| expatriate) | Iraqi/Iranian | ||||

| Iraqi/Egyptian | Iraqi/Romanian | Iraqi/Korean/Canadian | |||

| Iraqi/Egyptian | Iraqi/Canadian | ||||

| (Iraqi expatriate) | |||||

| Note. *Data from unpublished report (in Arabic) by NIC, "NIC Achievements for Year 2011", "Achievements for Year | |||||

| 2012", and Kurdistan Board of Investment (2014). | |||||