1.

ne of the most popular and far-reaching crosscultural research is that of Geert Hofstede. Hofstede was employed as an industrial psychologist and head of the Personnel Research Department for IBM-Europe during the late 1960s and early 1970s. His administration of a "values" survey to IBM employees in the 72 national subsidiaries of the company changed our view of managing across cultures. Based on the data analyzed, Hofstede concluded that management theories are culturally bound, and what may be appropriate management behavior in one culture may be inappropriate in another (Hofstede, 1980a;Hofstede, 1980b;Hofstede, 1983;Hofstede, 1993;Hofstede, 1994;Hofstede, 2001). Hofstede's research has been widely cited in numerous academic studies (Kirkman, Lowe & Gibson, 2006) and often forms the basis for cross-cultural training and analysis. Hofstede worked with data from his original countries surveyed and produced an analysis of forty O national cultures. Later research by Hofstede and others provided for the addition of ten more countries and three regions -East Africa, West Africa, and the Arab world (www.geert-hofstede.com, 2012).

The original dimensions of culture identified by Hofstede originally were power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. Power distance is the degree to which members of a society expect power to be equally or unequally shared in that society. Individualism is the extent to which people look after their own interests as compared with collectivism, in which people expect the group to look after and protect their interests. Masculinity is the extent to which people value assertiveness, competition, and the acquisition of money and goods. This is contrasted with femininity as a cultural dimension, which values nurturing, relationships, and a concern for others. Uncertainty avoidance is a society's reliance on social norms and structures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events (Robbins & Coulter, 2012). In essence, uncertainty avoidance is a measure of people's collective tolerance for ambiguity.

Later research (Hofstede & Bond, 1988) added a fifth dimension called long-term orientation. This dimension, originally called Confucian Dynamism, is the extent to which a society encourages and rewards future-oriented behavior such as planning, delaying gratification, and investing in the future. It is a cultural preference for thrift, perseverance, tradition, and a long term view of time (Robbins & Coulter, 2012).

Hofstede's popularity attracted a number of critics, some expressing concerns about the ability to generalize the results of his research and the level of analysis, as well as the use of political boundaries (countries) as culture. The validity of the instrument has also been challenged (Mc Sweeney, 2002;Smith, 2002). The homogeneity of culture, or in other words, the assumption that people are all the same in every culture has also been called into question (Sivakumar & Nakata, 2001). Relative to this study, there have been questions raised concerning the validity of grouping a number of Arab countries into one culture, because there are significant differences among Arab nations (Alkailani, Azzam & Athamneh, 2012; Sabri, 2012). The additional dimension of long-term orientation (LTO) has been challenged on the grounds of conceptual validity (Fang, 2003). Grenness (2012) points out the inherent problem of the ecological fallacy in Hofstede's work in which the predominant traits of a group are generalized to the majority of individuals within that group. In 2010, the Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS) published a special edition issue devoted to the improvement of cross-cultural research. Of particular mention were the Hofstede and GLOBE studies. This paper does not address those issues, and instead recognizes that all attempts to classify culture may have limitations. Even in the opening article of the JIBS series, Tung & Verbeke (2010) point out the "undeniable" impact of Hofstede's research on the theories and practice of management and international business.

This paper provides a preliminary look into the cultural assessment of a country not included in the Hofstede's data set. Afghanistan is a complex country consisting of both tribal and nontribal groups which influence national culture (Barfield, 2010). It is a country divided by rural and urban cultural values and one that seems to be always at war internally or with outsiders. An accurate empirical assessment of the totality of Afghan culture is nearly impossible. However, one can obtain some insight into the subset of Afghani culture that is perhaps most relevant for business and closely resembles the cultural findings of the Hofstede studies.

2. II.

3. Method a) Respondents, Survey Instrument, and Procedure

The assessment of cultural dimensions was made using a sample of 46 Afghani students studying business and economics at a university in Afghanistan. The sample consisted of 37 male and 9 female respondents. It was primarily, though not exclusively, comprised of urban dwellers. The survey respondents ranged between 19 and 23 years of age and represented the more elite segment of Afghani society.

In this study we used Hofstede's Values Survey Module 1994 (VSM 94), a questionnaire containing items developed for comparing the culturally determined values of people in five areas. The items measured respondents' perceptions of Afghan culture on the value dimensions of power distance (PDI), masculinity (MAS), individualism (IDV), uncertainty avoidance (UAI), and long-term orientation (LTO). Twenty items on the questionnaire measured the five cultural dimensions and six items assessed demographics.

The questionnaire was administered during class periods by the course instructor who asked students to voluntarily participate in the survey. Students completed the survey questionnaire anonymously and returned them to the instructor for analysis. The surveys were analyzed using the index method developed by Hofstede. This involved computing a separate score for each of the five value dimensions. The scores for the value dimensions obtained in this study were compared to the scores obtained by Hofstede in other countries of the world (www.geert-hofstede.com, 2012). Comparisons were made to seven select countries: Brazil, Denmark, Germany, Indonesia, Israel, Turkey, and the USA. Scores for each value dimension from the current study were also compared to those from respondents living in countries within the region to better understand the relative values. There were five countries included in this regional analysis: Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

4. III.

5. Results

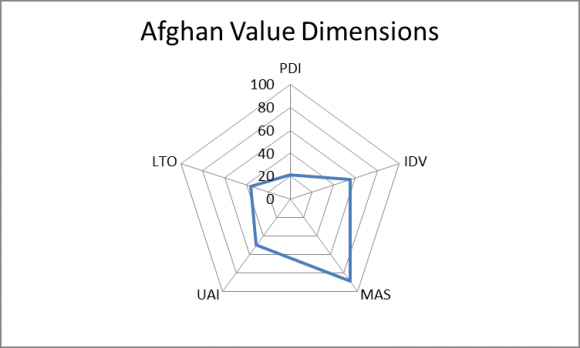

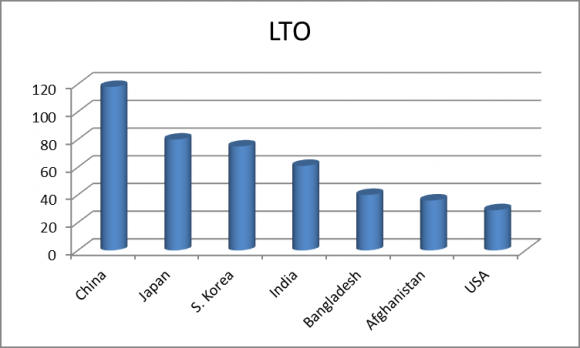

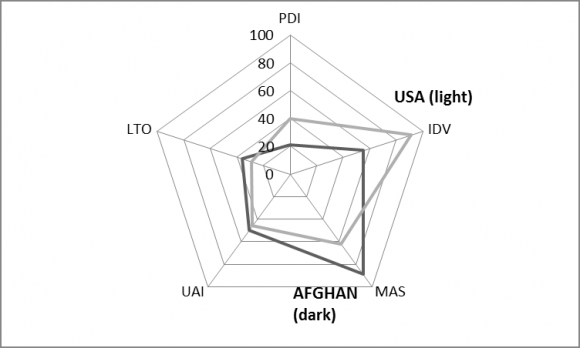

The results of the survey indicate that, in general, the culture of Afghanistan is low in terms of power distance, high in terms of masculinity, somewhat individualistic, moderately accepting of uncertainty, and short term in its orientation toward time. These results are surprising in that the value dimension scores for Afghanistan are different from other countries in the region. A typical values portrait of countries in the region would be high power distance, moderate in terms of masculinity, collectivist, and high in uncertainty avoidance. At this point in time people in Afghanistan appear to value the sharing of power, a higher degree of masculine behavior, a more individualistic perspective, and a greater acceptance of uncertainty. Long term orientation is difficult to compare since this dimension was studied in only 23 countries (Hofstede & Bond, 1988). The Afghani people have an even lower long term orientation than people from geographically-proximal Bangladesh and India, the only two countries in the region studied on this cultural dimension. The data indicates that Afghanis have a short term orientation to time. Interestingly, people from the U.S. have an even shorter orientation to time. Figure 1 shows the cultural values of Afghanistan relative to the Hofstede-Bond model.

6. a) Power Distance

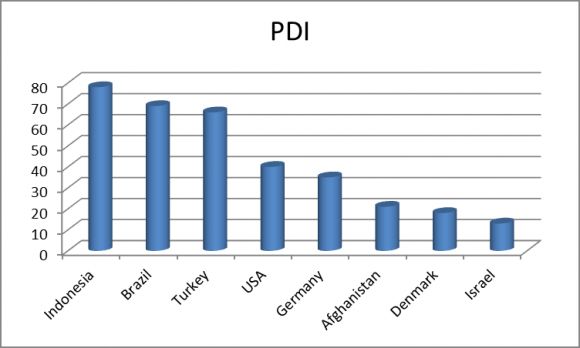

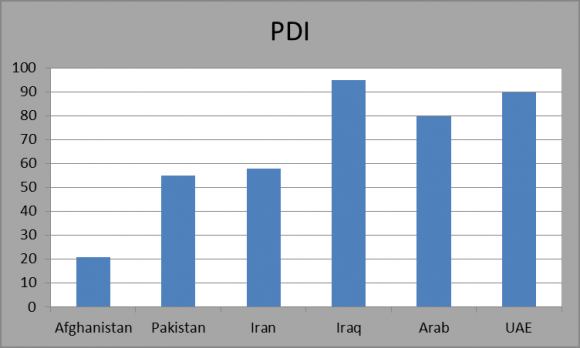

The data indicate that Afghanistan's PDI is 21. This score suggests that Afghanis have a low level of acceptance of inequality among societal members. Figure 2 shows the PDI scores for Afghanistan and select other countries. The data reveals that with respect to power distance, Afghanistan's culture is more similar to Denmark than it is to Turkey. Figure 3 shows that within the region, Afghanistan's PDI is most similar that of Pakistan, but markedly different from other countries. The average PDI score for the region is much higher than that found in Afghanistan.

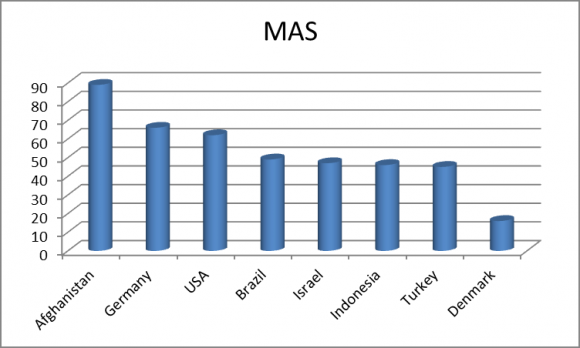

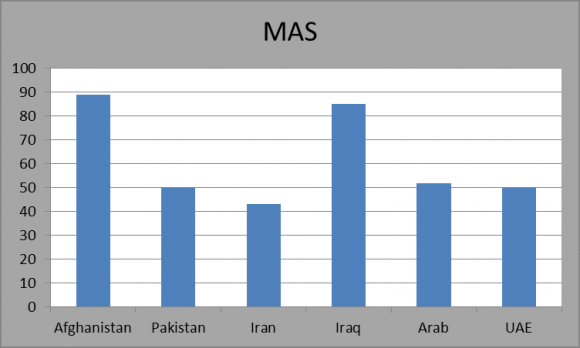

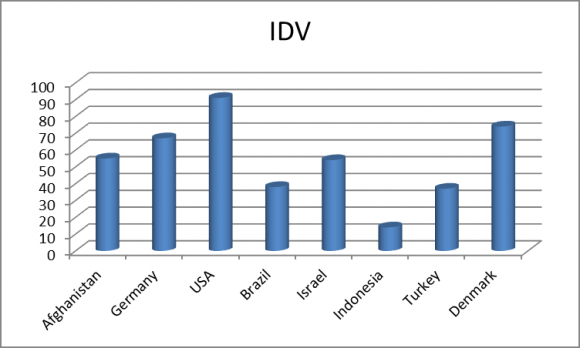

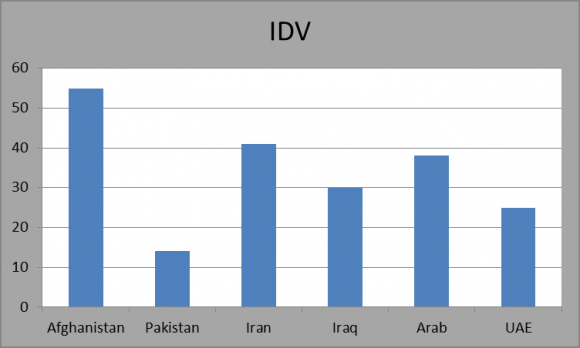

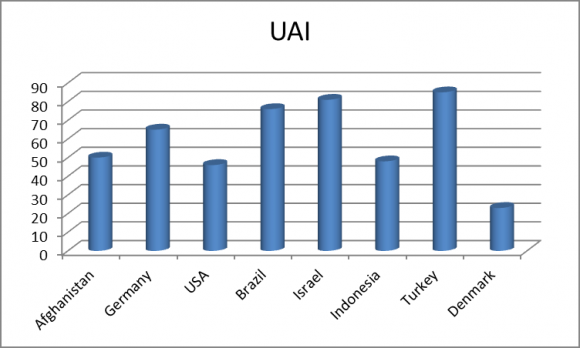

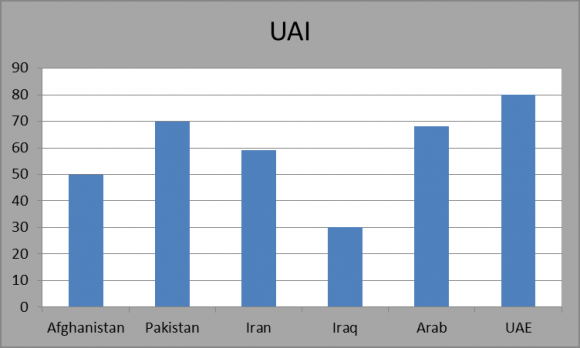

for the Economic and Political Future of the Country The data indicate that Afghanistan's MAS is 89. This score suggests that Afghanis have a culture that values dominant, masculine behaviors. Figure 4 shows the MAS scores for Afghanistan and select countries. The data reveals that Afghanistan's culture is more ma sculine or dominant than Germany and most other countries in the world. The data indicate that Afghanistan's IDV is 55. This score suggests that Afghanis are individualistic as a culture, placing it at odds with countries in the region, whose cultures are mostly collectivistic. Figure 6 shows the IDV score for Afghanistan and select countries. The data reveals that with respect to individualism, Afghanistan's culture is more similar to Israel than to Indonesia or neighboring Turkey, whose cultures are less individualistic and more collectivistic. The data indicate that Afghanistan's UAI is 50. This score suggests that Afghani culture has a relatively high tolerance for uncertainty. Figure 8 shows the UAI scores for Afghanistan and select other countries. With respect to uncertainty avoidance, Afghanistan's culture is similar to that of the USA. Figure 9 shows that within the region, Afghanistan's UAI score is most similar to that found in Iran. Other countries in the region have cultures with a greater uncertainty avoidance, except for Iraq, which has a lower score indicating a higher tolerance for uncertainty. The data indicate that Afghanistan's LTO is 36. This score suggests that Afghanis have a culture that is short-term oriented. Since this dimension was added nearly a decade after Hofstede's original study, we have comparative LTO data for relatively few countries. As such, comparisons with the Afghani data are difficult. Figure 10 shows the LTO scores for Afghanistan and six other countries from which those data were collected. The current data reveals that Afghanistan's long term orientation is similar to that of Bangladesh, but much lower compared to countries in the East: China, Japan, and South Korea. According to Hofstede and Bond (1988), cultures with low LTOs respect tradition, yet desire quick results. There is also social pressure to keep and advance one's social standing.

7. Global Journal of Management and Business Research

8. Discussion

While this study was not unlike the original Hofstede work in terms of sample heterogeneity, it is reasonable to conclude that the unique characteristics of the sample population do not represent the total Afghani population and wider view of Afghan culture. It is believed that the results are an accurate assessment of the urban, wealthier, educated segment of the population. Beyond this exploratory study, additional surveys using the VSM94 with more heterogeneous segments of the population would provide a more accurate description of Afghan culture. While the usefulness of the data reported in this paper for international business and economic development may be limited because of sample size, the findings should not be wholly discounted. Hofstede's initial data sample from Pakistan was limited in size with only 37 respondents.

The most surprising aspect of this study on culture may be the low power distance score found for the Afghani respondents. In the region of central and southern Asia it would be expected to find a much higher PDI score. While the low PDI may be a reflection of the sample, it may also reflect the lasting effect of the country's tribal societal structure. A country once ruled by a king gave considerable power and autonomy to tribes. Those tribes settled disputes and made decisions through a consensual process called jirga (Khapalwak & Rohde 2010). This power-sharing tradition may explain the low power distance score, but further investigation would be necessary to determine its cause. a) Geopolitical and Economic Implications Afghanistan, once a little known patch of mountains in a perceived unimportant part of the world, rose in visibility with the invasion of Soviet troops in 1979. With the subsequent withdrawal of Soviet troops and the rise of the Taliban, Afghanistan would once again gain international exposure with the terrorist attacks on America in 2001. Afghanistan remains important to American and allied foreign policy given the potential for additional terrorist activity and its proximity to troubled Pakistan. In addition to its geopolitical importance, the recent discovery of massive quantities of minerals, including the much coveted rare earth minerals in the country (Simpson 2011) make Afghanistan a potentially important economic entity. This potential source of wealth could help transform the country and its culture towards a more modern state.

The cultural values of the educated elite could be quite useful in moving Afghanistan forward. Of particular importance may be our findings related to the Afghani cultural dimensions of individualism and uncertainty avoidance. In order to build a modern economic system based on an entrepreneurial spirit it is helpful for cultural values to stress the importance of self-reliance and the acceptance of change. Individualism has been positively correlated with long run economic growth (Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2011). Afghanistan's moderately high cultural orientation towards individualism is especially promising in a country that is attempting to rebuild economically and politically. Having the ability to adapt to change, which is associated with a high uncertainty tolerance (low UAI score), is another factor working in favor of Afghanistan's desire to rebuild. While it is naïve to assume that massive change will occur overnight in this troubled country, there is some reason for hope that the educated leadership, along with economic resources, can begin to rebuild Afghanistan. In order to facilitate political change in Afghanistan's new democracy, it might also be useful to have leaders who possess a greater concern for power-sharing, especially given the power and influence of the country's tribal leaders. (Rothkopf, 1997;White, 2001). After more than a decade of occupation by NATO forces dominated by the U.S. military, there seems to be some degree of overlap between the cultural dimensions of Afghanistan and the United States, more so than would be expected. The overlapping is evident in Figure 11, which plots the scores on the five Hofstede dimensions for both Afghanistan and the U.S. While Afghanistan has a more masculine orientation and the United States has a more individualistic orientation, one would expect greater divergence in cultural values between these two countries. In that a discussion of the merits of the American and allied invasion as well as the occupation of Afghanistan is beyond the scope of this paper, it is worthy to note that the values of the Western powers may already have had some influence on the Afghani upper class development. History may teach us another lesson, especially the history of Afghanistan. In the end, there is reason to hope that the cultural values assessed in this survey may help bring about a more developed, tolerant, and peaceful country.